Jane Devine: Constitution plans to spark debate

When I went to see Lincoln on the big screen earlier this year, I was on the edge of my seat. Yes, I did know that the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery was indeed passed, but it was still gripping. I am also aware of the dangers in taking lessons in American history from Steven Spielberg, but the film did (I think successfully) portray the enormity of the event – not just the abolition of slavery, but the decision to amend the American Constitution which the people hold so dear and which has only been amended 27 times since its inception in 1787.

The American Constitution is the oldest in the world. Most other countries now have a constitution and many are based on this original model: enshrining the rights and responsibilities of citizens and, crucially, giving them guarantees which cannot be removed by successive governments.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBizarrely, that is one of the key reasons that the UK has no formal written constitution, with opponents believing that it would be undemocratic to bind future governments to decisions taken by their predecessors.

That argument, however, assumes that people want their lives viewed in five-year parliamentary terms, instead of a more meaningful time-frame such as, perhaps, their lifetime. It also assumes that this is about what successive governments want but, if done properly, a constitution is about what the people want, which tends to be more enduring than political will.

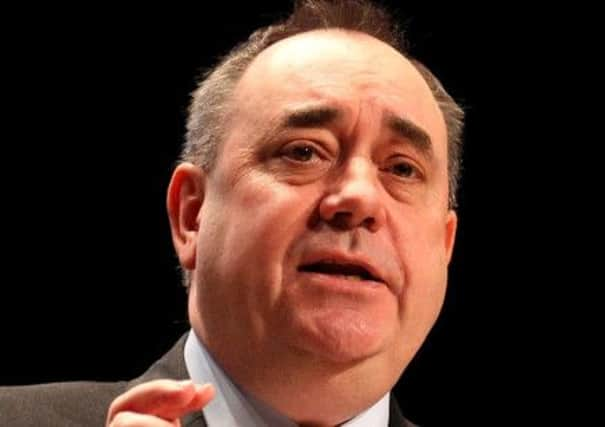

That is why unionist politicians in Scotland and Westminster should be cautious of dismissing Alex Salmond’s plans for a Scottish constitution in an independent Scotland.

When he made the announcement last week in Campbeltown, his speech was met with comments that it was not needed, not a priority and only likely to engage lawyers. As an abstract principle, I can see where the critics are coming from. However, if the discussion is about what might actually be in a constitution, that’s a very different story.

People want to know what they are getting from change. The euro, and membership of Nato and the EU are important, but don’t always seem that relevant to people in their everyday lives. However, if tangible ideas like a nuclear-free Scotland; the right to a free education; the right not to be discriminated against on the basis of gender; or the right to end your own life were discussed as possible articles in a constitution, they may well be things people would want to discuss.

When you get people to engage in a discussion about what an independent Scotland will be like, as opposed to whether or not an independent Scotland is something they want, then the debate has moved on dramatically.

The opening words of the American Constitution read ‘We the people...’. If Alex Salmond can use the prospect of a constitution to get people in Scotland two talk about what they want, he may just get the debate he’s been waiting for.