Jackie Kemp: The fine yarn of Scotland’s history

“Nations without a past are contradictions in terms. What makes a nation is the past, what justifies one nation against others is the past” – historian EJ Hobsbawn.

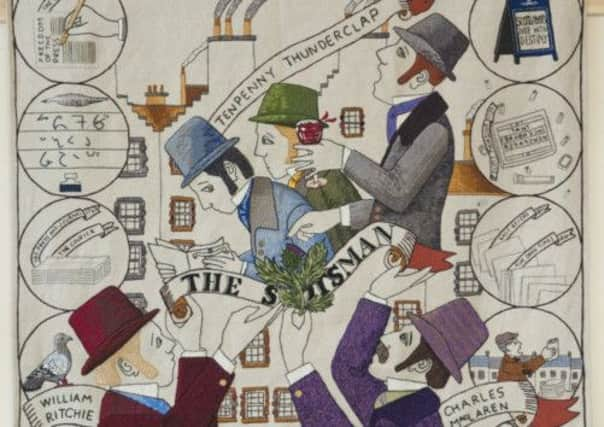

Today, for the first time, Scots will be able to see the Great Tapestry of Scotland at the Scottish Parliament. It is vast – the longest tapestry in the world. More than 1,000 stitchers have been involved in a literal and practical act of myth-making, which tells Scotland’s story in a series of beautiful handmade pictures.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a participant in a small way, I was admitted to the stitchers’ preview yesterday and found it a moving and exciting experience. Suddenly my own patchwork of knowledge of Scottish history has a vivid pictorial shape and timeline.

With this one single project, it seems to me, Scotland can truly say it has been reborn as a nation. It is a final piece of the jigsaw of Scotland’s artistic, cultural and political resurgence since 1999 and the reconvening of the Scottish Parliament.

I do not mean that Scotland will necessarily vote for independence in the coming referendum. But whatever the result of that, Scotland is clearly on a journey of increasing divergence from England.

That is illustrated, literally in this case, by the stories we tell ourselves about the past which we share – not through any ethnic or cultural ties necessarily – with the people who lived in the land we now inhabit.

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, Scottish history was not the main focus of history in schools. The historian Tom Devine has accused Scots of “historical illiteracy”, noting that when he began teaching the subject, students were so starved of knowledge that they found it “exotic”.

Britain was the nation of which Scotland was a part; it was North Britain, and British history was taught, with individual Scots having walk-on parts. The story went that union with the English had saved the Scots from a weak parliament, a feuding aristocracy and a joyless religion, and opened up opportunities for them within the British Empire.

Most British history books were anglocentric. Gibbon’s classic putdown in Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was that the Romans’ sojourn in Scotland was brief because they found little to detain them.

But there was a genuine British identity. When Scottish artist David Wilkie’s Chelsea Pensioners Reading the Gazette after the Battle of Waterloo was first exhibited in London in 1822, it caused a sensation. Thousands queued to see its careful synthesis of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish components in a great national victory.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScot David Livingstone was a Victorian celebrity who inspired a generation. It was the 21st century before any Scottish historians began to take a look at the grimmer side of the Imperial adventure.

For two centuries, Scotland had a special relationship with the British Royal Family. Queen Victoria took refuge at Balmoral with her loyal servant, John Brown.

On 1 June, 1953, the Glasgow Herald reported: “The Coronation gave the Gorbals the chance to dress up in its own crowning glory… the bunting has been stretched overhead. The result is so abundant one seems to look into a tunnel of dancing emblems with hardly a glimpse of sky.”

That was in marked contrast to the muted celebrations of the Diamond Jubilee last year. The Bank Holiday added on to the end of an English half-term fell in the middle of a school week for Scots. I was in the west Highlands which, unnoticed by the rest of the UK, was basking in a heatwave, and that perhaps contributed to the sense we had of being in an altogether different country. Pretty much the only Union Jack bunting I saw was on the television.

In my lifetime, one of the great engines of British myth-making were the trade unions. They told a story of working men and women across Britain standing shoulder to shoulder, with great reformers like Keir Hardie and James Maxton leading progress for the labour movement across the whole country.

Gordon Brown cited those figures yesterday in his big pro-union speech, calling on them as supporters of the Better Together lobby.

But to my mind, those engines stopped running after the miners’ strike. When British union power was broken by the Conservative government of the 1980s, a part of the whole notion of Britishness went too.

If British history is on the wane, Scotland’s story is at last being properly told. For most of the last two centuries, Scottish history has been more of a creature of folk song, literature and poetry than of the classroom. It was a kind of samizdat Scottish history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was Alan Breck Stewart evading capture in the heather, “Charlie is my darling”, Flora MacDonald bravely rowing the young bonnie prince dressed as her maid to a French ship in the dead of night. It was the “Floo’ers o’ the Forest are a wede awa’”, the mournful song about Flodden. It was Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson.

It was the John Prebble books about the tragedies and failures of the Scottish past: Glen Coe; the Darien Scheme. A drunk man looked at a thistle and, in the desolate empty glens, the winds blew through the roofless ruins of those who had been “cleared”.

Mary Queen of Scots had her head chopped off; the Covenanters were tied to stakes in the Firth of Forth; Jenny Geddes threw a stool; the Declaration of Arbroath – “For as long as 100 of us remain alive, tum te tum, but for liberty alone which no man relinquishes but with his life…” It was “Hey, Johnny Cope”, William Wallace and Braveheart. Robert the Bruce and the spider that tried again. Later on in the 20th century, it was the students who blew up pillar boxes emblazoned with ERII and stole the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey.

Jumbled up, half-understood romantic tosh much of it. But recently, a resurgent Scottish history has come about. There is a new interpretation of the past.

Arthur Herman’s book on the Scottish Enlightenment, How the Scots Invented the Modern World; Neil Oliver on the television; dozens of books about aspects of Scotland’s past. Tom Devine’s books have topped the Scottish best-seller lists. And Previoiusly… – Scotland’s History Festival – has hundreds of events planned for November.

Serious work is under way for the first time looking at Scotland’s role in the slave trade and empire building. There is a new vast tapestry in the wings called The Scottish Diaspora which will look at the warts-and-all reality of that in stitch.

Scotland has a history, and we are confidently telling it. The old anglocentric, partial and at times downright ignorant view of our shared history won’t do any more. It is disappointing to come across it in programmes like Lisa Jardine’s Seven Ages of Science on BBC Radio Four.

If Britain has any long-term future, it is as a political union of nations. Each will have to recognise the other if we are to work together in an atmosphere of mutual understanding.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Great Tapestry of Scotland seems a little cramped in the Scottish Parliament’s main hall. It would be wonderful to see it on show in a really large space, such as the entrance hall of the British Museum in London, and a great opportunity to share our story with our English friends.