Insight: Conspiracy theories - dawn of disbelief

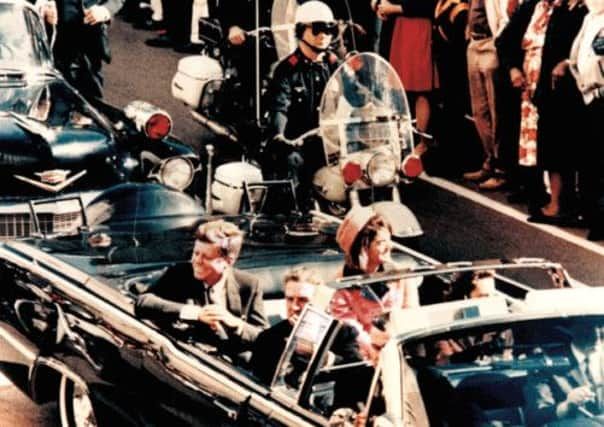

THE shots fired at President John F Kennedy’s limousine as it made its way along Elm Street in Dallas, Texas, 50 years ago this week, not only took the life of America’s most charismatic leader, they changed the nation forever.

In a few seconds, captured for posterity on Abraham Zapruder’s famous film, the hopes and dreams of a generation were snuffed out. It doesn’t matter that historians would later judge Kennedy less kindly, that they would point out his failures, such as the Bay of Pigs fiasco, or unearth details of his sexual infidelities. For those who lined the streets or crowded round their television sets to hear Walter Cronkite’s news reports, he was a symbol of youth, idealism and the promise of change and his assassination caused their world to tilt on its axis.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGiven their shock, it is hardly surprising US citizens craved a grand explanation. The one they were given – that the president was killed by lone gunman Lee Harvey Oswald, a man with communist leanings and mental health problems, later shot by Jack Ruby – was somehow unequal to the magnitude of the tragedy. And so the mother of all conspiracy theories was born. Oswald was not the sole perpetrator, but a patsy used to cover up a plot by the CIA, the Mafia, the Teamsters, Fidel Castro or white supremacists – you can take your pick.

Fifty years later, there has been no let-up in the public fascination with the crime, to the extent that more than 60 per cent of Americans now believe there was a cover-up. The shaky Zapruder footage is played and replayed, and alleged inconsistences in the eyewitness accounts and evidence presented to the Warren Commission pored over by people who were not even born when the assassination took place. The mysterious man seen putting up an umbrella, though there was no rain; the “magic bullet”, which is supposed to have taken a bizarre trajectory through the bodies of Kennedy and Texas governor John Connally; the smell of gunpowder on the grassy knoll and the mysterious “hobos”, arrested shortly after, are all as familiar to Americans as the official story: that three shots, and only three shots, were fired from the Texas School Book Depository.

The anniversary has been greeted with a fresh batch of books, most of them peddling some new conjecture about the way events unfolded. Last week, a documentary claimed Kennedy was killed by a stray bullet fired by secret service agent George Hickey when he realised the president’s limousine was coming under attack. But in the half century which has elapsed, the conspiracy theories surrounding JFK’s death have been joined by hundreds of others. Take any issue of significance from the mid-60s on: the moon landings, Roswell, Waco, the Oklahoma bombings or 9/11 – and there will be a group of people who challenge the official account of events and offer a sinister alternative.

In her book Real Enemies: Conspiracy Theories And American Democracy, Professor Kathy Olmsted argues that as the US government has grown bigger and more secretive, attention has shifted away from the perceived underhand dealings of religious groups, such as the Mormons or Catholics, and towards the covert activities of the state. “That’s something that accelerates as it becomes clear the state does sometimes conspire,” she says. “As those conspiracies are exposed, people say, ‘Well, if the CIA really were talking about trying to blow up Fidel Castro with a seashell, what else are they doing that we don’t have proof of?’”

More recently distrust has been fomented by Edward Snowden’s revelations that the NSA and GCHQ are snooping on our personal communications. But what distinguishes a conspiracy theorist from a mere sceptic is the degree to which their beliefs are impervious to evidence which undermines them. And in the lengths they believe the state is prepared to go to exercise its malign powers over the general population.

There are those, for example, who believe the Sandy Hook massacre, which claimed the life of 20 children and six adults in December 2012, was a false flag operation (an atrocity carried out by one faction with the sole purpose of tricking people into believing another faction was responsible) – perpetrated in order to justify the introduction of gun control measures. At the other end of the spectrum, some people believe comedian Andy Kaufman faked his death from lung cancer in 1984. That belief persists despite the fact that the woman who last week claimed to be his daughter has been identified by some as a New York actress, and his death certificate can be viewed online.

“Most of the time you can test a piece of information in a more or less scientific fashion and come up with evidence either one way or another,” says Dr Karen Douglas, reader in psychology at Kent University, who has written papers on conspiracy theories. “Conspiracy theories tend to be complex and quite nebulous so a lot of them are difficult to falsify.”

They are also reality-resistant because every time a piece of evidence that undermines them is uncovered, the alleged plot is broadened to encompass the scientist/academic/journalist who presented it. Whatever information these people have produced can be disregarded because they are complicit in the cover-up. Since what drives true conspiracy theorists is the conviction they are being lied to, it is even possible for them to endorse two contradictory propositions at the same time. Conducting research on a group of students, Douglas discovered those who believed Osama bin Laden was dead before the US raid in 2011 were also more likely to believe now that he is still alive.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGiven the implausibility of many of the prevailing conspiracy theories – followers of David Icke, for example, believe shape-shifting lizards control the world – why are they flourishing in the modern age? “One theory is that people like conspiracy theories because they feel powerless,” Douglas says. “They feel things go on behind their backs and powerful forces shape society. Conspiracy theories give them an explanation, a justification for why they might feel powerless, but at the same time, they allow people to feel they have information others don’t, that they can see the light when others are in the dark, which can, in itself, be empowering.”

Another factor might be a human desire to have loose threads neatly tied up as in a good detective novel. Instead of viewing inconsistencies in early news reports, witness statements or forensic evidence as inevitable in the aftermath of a chaotic and traumatic event, they hold them up as evidence that something untoward is going on. “As human beings we are pattern-seekers, we like to make order out of chaos and we like to tell stories that have a clear hero and villain,” Olmsted says. “Conspiracy theories satisfy those needs. They allow us to tell complicated stories in a simple way.”

Or simple stories in a complicated way. The official explanation for Princess Diana’s death – that chauffeur Henri Paul lost control of the Mercedes in which she was travelling – is a lot less convoluted than any of the propositions expounded by Mohamed Al-Fayed, whose son died at Diana’s side, all of which depend on sophisticated plotting and a large dollop of malign luck.

Unsurprisingly, psychologists have found that the types of people who are most susceptible to conspiracy theories are those most alienated from society; the distrustful, the disenfranchised, but also the Machiavellian – the more conniving people are themselves, apparently, the more likely they are to accept others might be plotting against them.

Conspiracy theories are flourishing in the age of the internet. Not only does the worldwide web make it easier for us to become amateur sleuths, it allows us to access a group of like-minded people who share our own world view. But there are other explanations, too, for the current upsurge in paranoia. “The country is becoming more polarised and political scientists say that when that happens conspiracy theories thrive because more people feel alienated and disillusioned, they really hate the other side and believe they are capable of all kinds of evil things,” Olmsted says.

Add genuine revelations about rendition and the existence of CIA black sites, and the discovery of traces of polonium in Yasser Arafat’s body, and you’ve got the perfect climate for conjecture and misinformation.

And now the JFK conspiracy theorists have another reason to suspect the authorities of trying to cover up the truth. Every year members of the Coalition on Political Assassinations gather on the grassy knoll at 12.30pm on 22 November to mark Kennedy’s death. This year they have been shunted out to make way for the official events. Yet they will not be silenced. They have printed up anniversary t-shirts which read: “50 years of denial is enough.”

Whether in Dealey Plaza or in their homes, America’s many conspiracy theorists are determined to make sure their version of events – however strange and unfathomable some of them may be – form a central part of the 50th anniversary commemorations. «

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1