Here’s the definitive answer to the Scottish currency debate – John McLellan

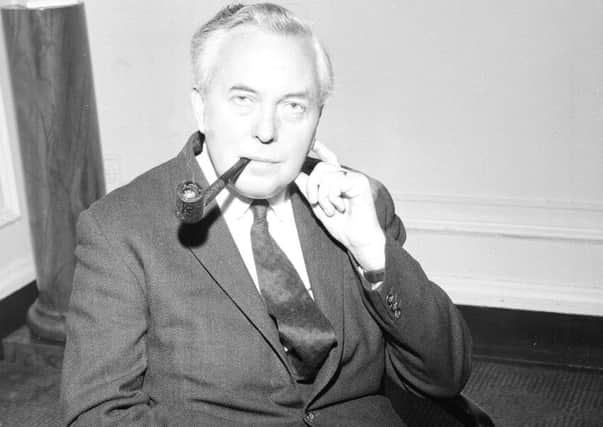

Like so many of the best catchphrases, Prime Minister Harold Wilson didn’t actually say “The pound in your pocket will not be affected”, but it stuck. What he told the nation in a 1967 TV broadcast when sterling was devalued by 14 per cent was “The pound here in Britain, in your pocket, your purse or bank account, will not be devalued”. Same difference.

The international currency markets might matter little to the general public other than at holiday time, but upheaval with something as fundamental as money not only creates havoc for the economy but saps public confidence in politicians like nothing else. Wilson never recovered and duly lost the 1970 general election to a Conservative Party whose leader Ted Heath could hardly be described as inspirational.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen in 1997 the economy was starting to motor, but it did nothing to save John Major who never recovered from the ignominy of Black Wednesday in 1992 when Britain tumbled out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism as the pound became the plaything of currency speculators like George Soros. So too, it could be argued, was Gordon Brown doomed from the moment RBS chairman Sir Tom McKillop picked up the phone to Chancellor Alistair Darling in October 2008 to tell him they were bust and effectively the entire British banking system was hours from collapse.

The political importance of financial confidence was not lost on Mr Darling and when private polling in advance of the 2014 independence referendum showed financial instability was a massive concern for a clear majority of Scottish voters, he played the currency card for all it was worth. With all the UK parties ruling out a currency share, Darling pressed the SNP to reveal their plan B, knowing full well that the only credible Plan B, an independent Scottish currency, would scare the bejaysus out of far more voters than it would attract.

In an attempt to solve the conundrum for a future referendum, the SNP’s Growth Commission headed by ex-MSP and RBS economist Andrew Wilson last year proposed a transition period during which Scotland’s £13bn deficit would be halved before moving to a new currency, which has the triple benefit for Unionists of first promising maximum austerity, then currency upheaval and a bitter row amongst grassroots Nationalists along the way.

Finance Secretary Derek Mackay and SNP deputy leader Keith Brown have now put a motion to the party’s spring conference to make the adoption of a new currency after independence official policy, and although this has been welcomed by some as clearing up the confusion which dogged the Yes campaign it doesn’t make it any more palatable. Plan B was never publicly acknowledged because the SNP strategists knew as well as Better Together that a new currency was a turn-off and nothing suggests attitudes have changed. But if there is ever to be a re-run of 2014 it makes the choice much more stark.

Thanks to Brexit we now know beyond all doubt that political and economic chaos would follow a vote for independence, and to that would be added the prospect of an untried currency and a government with no track record of financial prudence. The new government’s borrowing would be cripplingly expensive and it’s against this sort of background that an audience of about 200 business types and politicians gathered this week at the Edinburgh International Conference Centre to hear about the proposed re-establishment of a Scottish stock exchange by accountant and entrepreneur Tomas Carruthers.

Business-minded Nationalists such as ex-MP Michelle Thomson, ex-Enterprise minister Jim Mather and Edinburgh Lord Provost Frank Ross are prominent among its supporters – and they see a stock exchange as a vital institution in the development of an independent economy. But while the Growth Commission report was referenced in an accompanying 36-page prospectus, passages on Scotland’s economic future made no reference to a new currency.

Scottish stock exchanges existed for hundreds of years, gradually drawn together for efficiency into a single Scottish Stock exchange which was then absorbed into the London exchange in 1973 and, while the ultimate aim might be to construct a component of future statehood, its success or failure does not so much depend on political independence but on offering something different (in this case a focus on renewable energy) and on its ability to raise capital and generate profitable investment.

The 2014 independence blueprint “Scotland’s Future” made no mention of a stock exchange and it was commented on at the time that it would be strange for an independent country not to have its own exchange. It does not follow that an exchange needs an independent country, but it certainly needs a reliable currency with which to trade. That would be the pound.

BBC should wince

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBBC Scotland news magazine anchor Martin Geissler was quick to tweet after my observation last week that I was sure I saw him wince at some of what was going on around him in the first editions of his show The Nine.

“For info I wasn’t wincing. Proud to be involved in the project ... A fresh, exciting programme, I reckon,” he wrote. Fair enough, but I wonder if he winced when the audience estimates for the first week came through, fluctuating from around 12,000 to 24,000.

Up-to-the-minute figures aren’t publicly available and the BBC is probably not going to provide a running commentary.

But with a £7m budget and 80 new journalists, they might think twice about sniffy reports heralding the demise of the Scottish newspaper industry every time hard copy circulation figures are published. People actually have to buy newspapers, not just switch on the box.

A scoop of journalists

Someone who knows all about the BBC is its former Director General Mark Thompson, who left in 2012 after eight years at the helm to become chief executive of the New York Times. He’ll be just across the water from BBC Scotland’s HQ in June when he is appearing at the World Association of Newspapers’ annual congress at the SECC, the first time the event has been held in the UK. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt are also expected at what will be the most significant gathering of publishers and journalists in Britain for many years.