Gregor Gall: Union inquiry moves in on leverage tactics

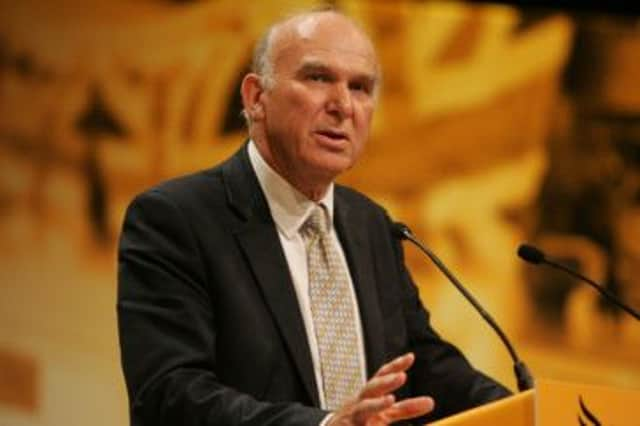

This is because there is a clear politically opportunistic intent to the inquiry – in short, to attack Labour, first smear Unite. Indeed, Liberal Democrat Business Secretary Vince Cable made it plain that he only agreed to the inquiry if it would also examine employer practices (including blacklisting).

So what exactly is the “leverage strategy” as Unite calls it, and does it routinely involve the targeting of individuals and demonstrating outside their places of residence as was the case with Ineos?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe thinking behind “leverage” comes from attempts by American and Australian unions to work out new ways to put pressure upon an employer in a situation where the old ways seldom still work. So as a result of falling membership and weakening power, a bit of blue-sky thinking was engaged in. This led to the realisation that the key to rebuilding workers’ power at work did not always lie in the workplace.

The best examples are the Justice of Janitors and Cleanstart campaigns of the 1990s. Instead of targeting the cleaning contractors to improve wage and conditions, American and Australian unions focused on the clients (like banks) that used the cleaning companies. Through actions which damaged their reputations, unions compelled the clients to pay the contractors more to improve wage and conditions. The actions comprised events which were not only media-savvy but disrupted the smooth running of the clients’ operations.

Translated into Unite’s hands, the leverage strategy is not just about creating reputational damage, but far more about applying pressure on one particular employer by targeting its suppliers and buyers. In the context of lean production and just-in-time operating systems (where no stocks exist) and relations of monopoly (one seller) and monopsony (one buyer), Unite has identified weak points in the chain of production, distribution and exchange.

So in the case of the white meat (chicken) processing sector, Unite was able to increase its members’ wages by targeting the large retailers that buy the produce in a monopsonistic manner. For example, Unite would target Sainsbury’s or M&S with demonstrations outside shops, headquarters and shareholder meetings to highlight the ethical and business case for purchasing its chickens at a price that allows the processor to pay higher wages.

But processors would not be left untouched either. Demonstrations outside their factories and some industrial action inside them too would highlight to them that if they failed to get sufficient quantities of chickens on to the supermarket shelves by the required times, then they could be penalised by the buyers and, ultimately, lose the contract.

Another supermarket, Tesco, was affected by the Unite strategy. Tesco transferred its Doncaster distribution workers to Eddie Stobart which then made them redundant. The workers responded by picketing the depot with their supporters in order to stop incoming trucks. Not only did this cause huge motorway traffic jams but it stopped goods getting on to the Tesco’s shelves.

Putting together potential reputational damage and disruption to production has meant Unite has developed an effective tool.

The irony is that this form of leverage was not displayed at Ineos. Sustained targeting of individuals along with places of residence was very much an aberration. Yes, individuals like venture capitalists have been pursued before. For example, the GMB targeted Damon Buffini, head of Premira private equity group, outside a church with a camel and the biblical proverb, “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” in its battle to stop the asset-stripping of the Automobile Association. But this was a one-off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOften Unite’s leverage work has been taken in conjunction with campaigning allies like UK Uncut or its community members (those who are Unite members but do not work, like the unemployed or pensioners).

The reason Ineos departed from the script was not only that the dispute escalated rapidly and dramatically so that Unite did not have time to lay its normal groundwork. It was also because Ineos is a very peculiar company. Being called “the biggest company you’ve never heard of” meant it was difficult to target Ineos’ reputation, or even think about a consumer boycott because Ineos does not sell directly to the public. The supply chain was far more complex than that of the supermarket and chicken processor.

This innovation in strategy and tactics is a direct response to the laws that the Conservatives introduced in the 1980s and which Labour maintained in the 1990s. Secondary action such as the “blacking” of goods is no longer within the domain of a legitimate and lawful trade dispute with an employer. This means workers in one company cannot force another company to pay its workers better wages by refusing to handle its goods. Neither can they picket a workplace which is not their own to help other workers.

Unfortunately, it’s unlikely (even with Mr Cable’s help) that the inquiry will be capable of understanding the causes of the leverage strategy. Neither will it put forward positive alternatives (like compulsory arbitration) if it seeks to disavow unions from using leverage tactics.

• Gregor Gall is professor of industrial relations at the University of Bradford