George Kerevan: Smarter to look beyond horizon

AND so another Scottish company bites the dust. With the takeover of Edinburgh-based Wolfson Microelectronics by Cirrus Logic of Texas, Scotland has lost one more of its once-promising hi-tech firms to a foreign competitor.

Cirrus is what is known euphemistically as a “fabless” company. In other words, it makes money from owning patents for electronic hardware but outsources the actual manufacturing to “foundries” (another euphemism) in China. For foundry read factory where there are real jobs (And yes, I know that Wolfson is also a designer rather than a manufacturer. But if you have a secure domestic research base you can command where the final manufacturing takes place. Currently, helped by cheap energy and a cheap dollar, US companies are busily repatriating jobs from Asia.)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI have a soft spot for Wolfson Electronics because, in its very early days, I arranged to put some Edinburgh Council seed money into the firm as venture capital. Perhaps you’ll tell me that local councils are better employed in collecting the rubbish bins. No, they’re not. Councils should be civic economic leaders with a role in creating local competitive advantage, because no-one else will.

Wolfson began life at Edinburgh University’s King’s Buildings back in 1984. It was started by two talented entrepreneurial academics, David Milne and Jim Reid. The company designs widgets used in the audio systems of smartphones, tablets, and anything digital. Unlike a lot of other hi-tech businesses, Wolfson does not rely on just one “wonder” product – it has gone on innovating.

But the life of hi-tech innovators is a tough one. The product cycle – from initial idea to teenage bedroom – gets ever shorter. One false investment can destroy the commercial power of a household name overnight. Witness: Palm, Nokia and BlackBerry.

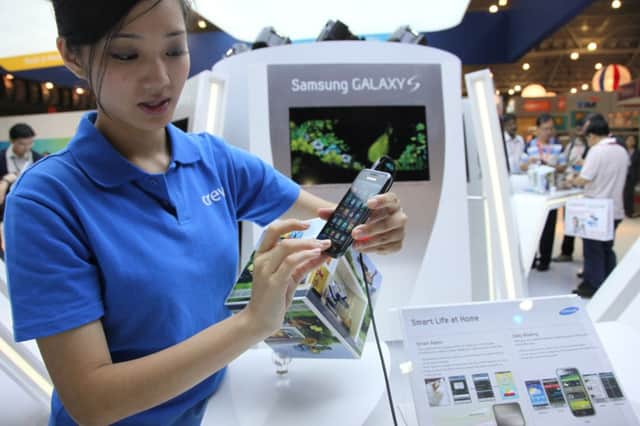

Wolfson is another victim of the mobile-phone war. It supplies the chip architecture for the 3G version of Samsung’s Galaxy smartphone. Even last year that seemed to assure Wolfson’s future, as Samsung was outselling Apple in the global smartphone market, on price and popular appeal. Wolfson reported a whopping 59 per cent increase in sales in the first quarter of 2013. (At the same time, Apple’s problems left Cirrus with a glut of audio chips, sending its revenues and share price sharply down.)

Then the fickle smartphone market changed again. Samsung is still beating Apple, but sales of its 4G devices have mushroomed unexpectedly as the world takes to being permanently online. Unfortunately, Samsung 4G equipment uses a rival system to that supplied by Wolfson. Result: the Edinburgh firm made a loss of £7.7 million in 2013.

In itself, however, a temporary loss of £7.7m in the race to dominate global communications technology is a mere blip. Hi-tech innovators and shareholders expect to lose money – lots of it – for ages. That is the essence of risk-taking. Besides, Wolfson has new technology coming through plus assured customer links with Sharp and Lenovo, as well as Samsung. Which is why Cirrus is happy to pay a premium above the current Wolfson share price.

Cirrus is paying a measly £291m for Wolfson – small change in the hi-tech world. Yet Cirrus made revenue of only £428m last year. Cirrus is paying for Wolfson’s products, patents and research capability partly by borrowing – £135m to be exact. Which gives rise to a question: why couldn’t Wolfson have raised the money to buy Cirrus and create a Scottish audio giant? As it is, Cirrus has now (for a pittance) secured both Apple and Samsung as customers, giving it immense market power.

Yet Cirrus is no giant. It has 751 employees while Wolfson has 437. What Cirrus does have is the vision to see that you have to get your retaliation in first. Cirrus has decided to grab ideas by buying other companies – a smart move. You could see what Cirrus was up to last year when it bought Acoustic Technologies, a US leader in voice processing technology. Why is this important? Because we are at the dawn of voice-activated devices. Forget those insanely fiddly smartphone keypads – soon you will talk to your computer. And probably contribute to Cirrus profits, as a result.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe real lesson of the Wolfson affair is that Scotland (or the UK, for that matter) had no investors willing to take a long view of innovation. Put another way, the London stockmarket was only willing to mark Wolfson down to a giveaway price, when the majority of analysts were recommending “buy”. So the Americans did. This risk-averse culture is the result of many things. Of Labour and Tory governments favouring the financial sector over manufacturing. Of a tax system that penalises long-term saving and investment in favour of consumption and house purchase.

The loss of Wolfson is bad for Europe as well as Scotland. Only nine of the world’s top 100 hi-tech companies are European. What is the problem?

Simple: Europe’s largest hi-tech firms spend a fraction of the cash on research devoted by their US and Asian rivals. Samsung invests £8 billion a year in R&D, and employs 65,000 research staff.

This says to me we need an industrial policy in Scotland aimed at reviving manufacturing. One reason I favour Scotland voting Yes in September is that it provides the best chance of freeing us from the economic domination of the City and from its short-termism. It will allow a Scottish government to frame fiscal rules that favour industrial research and long-term risk-taking.

This is not an argument that suggests civil servants can pick industrial winners better than the market – they can’t. It is an argument to refashion Scotland’s fiscal architecture to promote industrial investment over gambling in short-term share values or property booms.

Britain and Scotland don’t have the entrepreneurial, risk-taking environment we find in America. We have the opportunity to create that in an independent Scotland. Or sit back and watch the rest of our hi-tech firms be bought from under our noses.