George Kerevan: Austerity be damned

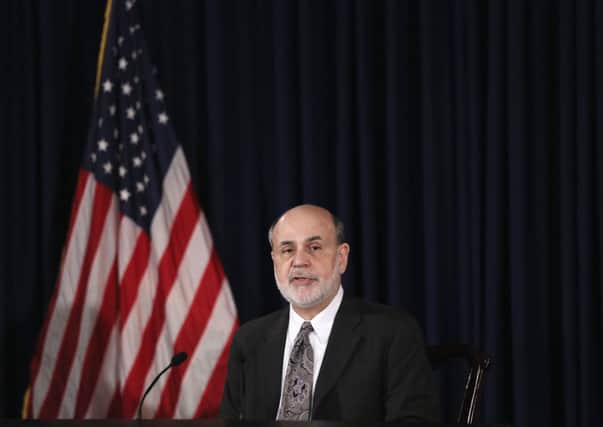

It is the end of an era. Wednesday, 18 December 2013 will be one for the history books. On that date, the boss of the US central bank, Ben Bernanke, signalled that America was ending so-called Quantitative Easing (QE) after five long years of economic crisis. The US has turned the economic corner and (probably) the world with it. Can we really start enjoying ourselves again?

Actually, Bernanke is merely winding down QE (aka printing dollars to buy bonds in the market place) by a smidgen – $10 billion per month. The US central bank will still be printing $75bn every four weeks and using the new cash to buy outstanding bonds, ie: loans already issued to build houses, finance companies and pay for government spending. That’s equivalent to about one third of Scotland’s annual gross domestic product.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy buying bonds hand over fist, Bernanke has pumped huge amounts of liquid cash into the US economy and, as a result, into the entire global economic system. Buying bonds like this has boosted their price, lowered interest rates and made investors feel safe. These happy investors used the extra liquidity to buy company shares, boosting the US stock market and reviving business confidence. Bernanke has also purchased mortgage bonds – packages of private house mortgages – thereby pumping more lending power into the US property market. Result: a revival of the American house market and a boost to consumer confidence.

Today, the US economy has definitely recovered from the dark days of 2008 when its financial system came within a hairsbreadth of imploding, taking the manufacturing economy and private savings with it. Since then, Bernanke has printed (electronically) and spent nigh on $3.2 trillion in QE. That’s about 133 times Scottish GDP. However, the result has been a spectacular success, with unemployment dropping like a stone. Better still, the US economy is undergoing a manufacturing revival fuelled by cheap energy from fracking.

In fact, all those countries that adopted variants on QE have seen their economies turn round. The UK adopted a variation of QE, with the Bank of England printing £375bn to buy bonds. Though the Bank was more conservative than the Federal Reserve, and bought a narrower range of bonds, the UK economy has now returned to growth and lower unemployment. The Swiss followed the same course and have bounced back – proof, incidentally, that a small independent nation could easily (and quickly) handle a major banking crisis on its own by following the correct policies. After two decades of depression, the Japanese have jumped on the QE bandwagon, provoking a remarkable recovery.

Which is the odd economy out? Answer: the EU, where the powers that be in Berlin have mandated fiscal austerity as the route to economic recovery while rejecting QE. Result: the longest recession since 1945 plus truly horrendous unemployment in the Mediterranean bloc of countries. The OECD think-tank predicts eurozone unemployment will be above 12 per cent for years.

The eurozone austerity plan is supposed to cut public debt in order to boost the private sector. However, this is the trivial economics of running a household. National economies and public budgets simply do not work this way. By cutting public spending and raising taxes too much, too quickly, the eurozone produced the opposite result of what was intended. Economies imploded, so tax revenues collapsed – forcing governments to borrow more than planned. At the same time, depression caused prices to fall, increasing the real value of public debts.

So we get the following counter-intuitive result. In America, where the federal government continues to borrow and spend heavily, the annual deficit has plummeted to 3 per cent of GDP, from a peak of 12 per cent back in 2009. But that is far less than the eurozone economies using crude austerity measures to try and cut borrowing; eg: Ireland (7.4), Spain (6.8), Portugal (5.9), Greece (4.1), or even France (4.1).

In a private household you have to spend less than you earn to pay off your credit card. But countries are different. Provided the economy (including inflation) grows faster than the total stock of debt, the debt mountain starts to diminish in relative size and is therefore easier to fund. That’s what QE has ensured in the US. Hence you get both economic recovery and lower debt, and with much less human pain.

In the UK we have followed a middle course – with middling results. On the one hand, the Bank of England has cranked out QE to reasonable effect (it could have been bolder, in my opinion). On the other hand, Chancellor George Osborne implemented austerity on a par with the eurozone, thereby slowing the economy more than was necessary and creating a second economic dip last year. This year, Osborne quietly backtracked and pumped subsidies into the housing market, creating a mini boom. But he is still threatening to run a budget surplus after the 2015 general election through a further round of huge spending cuts – goodbye Scotland’s Barnett consequentials.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhy bother? A combination of QE-induced monetary confidence, economic growth and gentle inflation is eliminating the worst of the UK’s deficit. Osborne’s austerity rhetoric is obsolete. The worst thing that could happen in Britain is if an ideologically fixated Osborne kills the boom by resorting to the daft austerity being imposed in Europe. Are there downsides to QE? Certainly. Buying bonds stuffs new dollars or pounds into the banks and hedge funds. This makes the rich richer by causing stocks and other paper assets to jump in value, without anyone doing any real work for humanity. My preference: spend the newly printed cash directly on building houses, schools and hospitals.

QE has also boosted London because that’s where the financial system is concentrated. In the words of Vince Cable, London is now sucking the lifeblood out of the other nations and regions in the UK. But that’s another story.