Fiona McCade: When life aspires to imitate art

Peter Paul Rubens is lucky he is not alive today. If he were, he would be pilloried for encouraging obesity in women. “Rubens paints another fat lass!” the tabloid front pages would scream. “What hope for educating our daughters to eat healthily?”

Luckily for him, he has been dead for 374 years, so he is well out of it, but the debate about body image – and who is to blame when some women get confused about theirs – rages on.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn an interview this week, Alexandra Shulman, editor of British Vogue sighed that she’s now “bored” of answering questions about the way her magazine appears to idealise stick-thin models.

Shulman has received criticism for this admission, but then she’s used to criticism, as Vogue rarely shows any kind of imperfection in its pages. Nevertheless, I feel sorry for her, as she’s one of the few fashion mavens who has consistently spoken out against the tyranny of Size Zero.

However, after 22 years at the helm, she knows what sells. “Nobody wants to see a real person looking like a real person on the cover of Vogue,” she said, and she’s only being honest. Magazines like hers are not about the likes of you and me. They’re not even about what the likes of you and I can afford; they’re practically art – and if they are viewed as art, then they suddenly start to make sense.

Fashion photography has as much to do with everyday reality as a Rubens in an art gallery; interesting to look at, but from a different universe, on a different plane. And if the woman in the street understood that, and accepted that her copy of Vogue does not imitate life, then the world might be a saner place.

However, she doesn’t always. All over the world, there are women starving, cutting and moulding themselves into shapes that they were never meant to be. We can blame the glossy magazines to an extent, but it wasn’t always like this. Something has changed. Even in the relatively recent past, the magazines were still glossy, but ordinary women weren’t so desperate to emulate the models within. So, what’s happened to us?

I think the answer lies in something else Shulman said in that interview. When asked what sort of image she would put on the cover of Vogue in order to sell the most copies, she said: “The most perfect girl next door.”

And that’s when it hit me. Of course, women want to look good, we always have. But in the past, the differences between art and reality were clear. For example, the models in the 1950s were clearly a species apart. They looked relatively old – nice for the over-30s; no need to rush to have surgery at 25 – and their severe expressions and even more severe, corseted waistlines showed that they were creatures from the world of art, rather than the real world.

They were like goddesses, come down from Mount Olympus; something to gaze at in awe, but impossible to copy, so mere mortals were content simply to look as good as they could. And no more.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

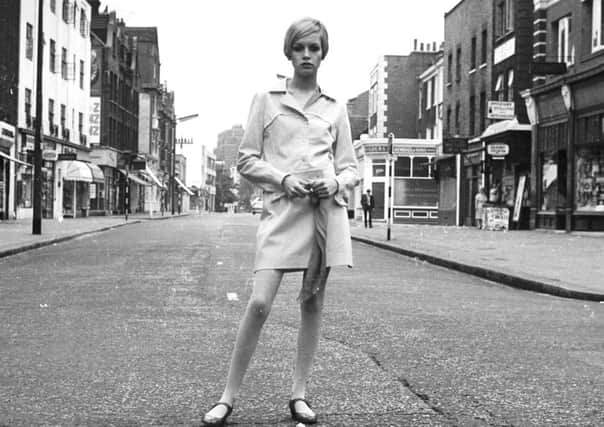

Hide AdThen came the 60s, and out went the remote, statuesque mannequins of old and in came models such as Twiggy. The perfect girl next door. And I think this is where the line between art and reality started to blur.

I’m not blaming Twiggy and her ilk – they knew they weren’t perfect – but, for the very first time, an ordinary woman could look in a magazine and see someone who looked ever so slightly like her. Someone who appeared to be natural. There was a chance that, with a little bit – OK, a lot – of weight loss, and the right make-up and hairdo, she could emulate a fashion model.

Aspiration was born, and we’ve been aspiring ever since – and killing ourselves to do it because, of course, the images we see aren’t natural. Even when the model appears to have been freshly dragged through a hedge in order to be photographed, the images aren’t natural.

Unfortunately, many young women still believe that they are. The more everyday and next-doorsy a model looks, the more she inspires thousands of genuine girls-next-door to try and look like her – because it seems possible.

Nowadays, you can open a glossy magazine and see models glaring balefully back at you who wouldn’t look out of place in a police line-up. This is where art becomes artful, because the trickery involved in making them look desirably cool is so imperceptible, many a young woman ends up thinking: “Wow, if that feral, drug-addled bint can make it as a model, why not me? All I have to do is lose three stone and I, too, can be a fashion icon!” And off she goes, to spend the rest of her life eschewing carbs and making herself – and everybody around her – miserable.

So, while the fashion industry wants nothing to do with “real” people, it still attempts to present us with the girl-next-door, just with a little added perfection. This contradiction gives hope to gullible girls, where in fact there is none.

Just as Nature abhors a vacuum, Vogue abhors Nature. Years ago, this important difference between artifice and reality seems to have been understood, but, now, some women have become convinced that this dazzling fantasy bears some relation to normality.

Vogue is to everyday life what Damien Hirst’s shark is to angling. Shulman realises this, but it’s her job to provide what sells. So, if we’re stupid enough to buy make-believe and believe it, we have no-one to blame but ourselves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf you ever feel oppressed by the fashion industry and its unfeasibly skinny idols, just remember, none of it exists. It’s just art.

And if you like art, why not hang a Rubens print on your wall? Then, whenever the skeletal bodies in Vogue make you feel like dieting, feast your eyes on Peter Paul’s buxom beauties, and treat yourself to another doughnut.