Euan McColm: Poor exam results don't have to be the end of the world

With the rise of social media has come an annual tradition on the day teenagers receive their exam results: well intentioned, if self-regarding, individuals will mark the moment by reassuring young people that qualifications aren’t everything.

“I failed all my Highers,” a bloke will tweet, “and now I’m a regional manager for B&Q.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I bombed at school,” a woman will add, “and I ended up in The Spice Girls and I met Nelson Mandela.”

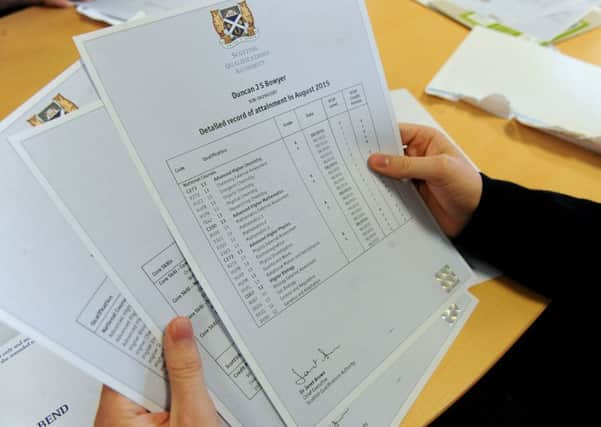

Undoubtedly, results day – today in Scotland – can be the most stressful time. The receipt of my own Higher results was soundtracked by the clang of disappointment. I had suspected that dogging French on Mondays (then record release day) to spend my paper round cash in HMV and Virgin on Glasgow’s Union Street might have bleak consequences and, it turned out, I was correct. I would not be enrolling at university a few weeks later. Nor would my pal, Ian, and we commiserated by drinking, between us, a dozen cans of Red Stripe lager.

By teatime, not only was I an academic failure, I was throwing up in someone’s garden.

I was fortunate. In those days, it was perfectly common to enter journalism straight from school. In common with other trades, learning was done on the job. A taste for drinking Red Stripe in the afternoon was no impediment to entering my trade and, after a couple of interviews, I was a trainee.

I could, I suppose, offer myself up to teenagers as an example of someone who didn’t get the results he hoped for but still went on to forge some sort of career doing what he’s always wanted to do.

But, if I did so, I’d be talking about different times. A focus on university rather than on-the-job training in any number of industries has made it that bit more difficult for teenagers with less than stellar results to get on.

Among the 40-somethings I went to school with is a senior manager in a large financial organisation. He got in as a trainee with two Highers in 1987. Today, his route would be blocked by his failure to have obtained a degree.

Don’t get me wrong: I am not one of those “I went to the university of life” berks that you meet. I hugely regret not going to uni and, to this day, I wonder whether my thinking might be sharper, my analysis clearer had I done so.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPlatitudes from people whose experiences are the exception rather than the rule – after all, most poorly qualified people can expect to make very little money doing very dull jobs – won’t, I suspect, come as much comfort to school-leavers, today, who’re entering an adult world where increasing numbers of their peers will go on to graduate.

Among young graduates, stories of being forced to accept menial jobs for which they are overqualified are commonplace. What chance, then, does a kid who didn’t make the grade on exam day have of starting any kind of career?

University education has been a focus of the SNP, which frequently asserts the merits of the abolition of tuition fees (for Scottish and European but not English) students. But that policy has come at a cost, most notably the loss of more than 130,000 places at Scottish colleges.

Yet more bad news, then, for those who messed up their Highers and who might once have seen the attainment of a Higher National Certificate or Diploma as the first step on a different route to university. This focus on Higher rather than Further Education means fewer options for kids who may not shine academically but have potential worth developing.

The Scottish Government might insist the free tuition fees policy is designed to make university more accessible to those from less affluent backgrounds but the fact is that a teenager from a wealthy family in Scotland is three and a half times more likely to apply to study for a degree than a teenager from a deprived family. This is a worse record than in tuition fee-charging English universities where better off kids are two and a half times more likely than poorer kids to go on to Higher Education.

Free university tuition might tickle the fancy of the affluent middle class but we’re surely past the point where we should have stopped and asked whether it was the right thing to do. Not every school leaver is academically prepared – or wants – to attend university. Unfortunately, the options for those who might want to take a different path are few and growing fewer.

Is the loss of college places for ambitious kids from poorer backgrounds a price worth paying for the privilege of providing free university tuition to wealthy youngsters? We can continue to complacently accept the myth that this flagship policy is a fair one or we can start to ask difficult questions. I’m in favour of the latter course.

A hellishly competitive jobs market and the prohibitively expensive price of property means young people leaving school this year have every reason to be stressed. So, before tweeting that you did okay without getting a pass in Higher German, please consider whether you might provoke rather than reassure.

And if you’re a teenager who didn’t get the results you wanted, it really isn’t the end of the world. But do think about resits.