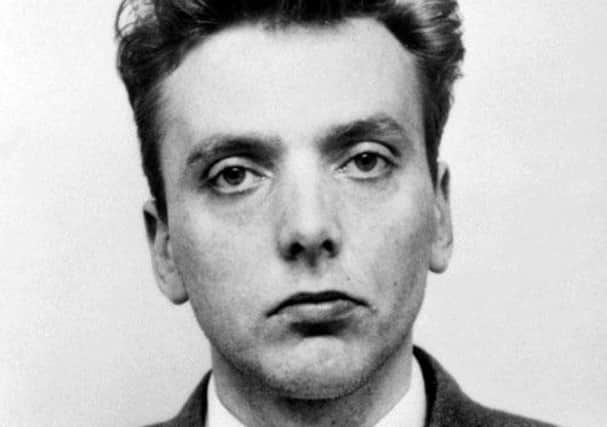

Dani Garavelli: Playing into the hands of Ian Brady

It’s so long ago, and I’ve read so much on Ian Brady and Myra Hindley since, that I can’t recall a great deal about its content, other than that it tried to emulate the style of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. But I still remember the front cover of the tattered hardback version on our bookshelves – a stark image of a spade with mud on it which I found so chilling I had to turn it over so I couldn’t see it in my bed at night.

I’m not sure if Brady’s right, if my abiding fascination with his crimes does have something do with their location – certainly Saddleworth is a desolate and unsettling landscape – but, in common with many other people, I have long had a compulsion to find out more. It’s as if, hidden somewhere amongst the hundreds of thousands of words that have been written about him, lies the key to unlock the mystery: what turns a human being into the kind of monster who tortures and kills for the “existential experience”? And then there’s the question of his relationship with Hindley. Almost half a century on, we’re no closer to understanding the complicated dynamics which led them to share and act out their sadistic fantasies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBrady, along with a handful of other 20th century serial killers – the Yorkshire Ripper, Robert Black, Dennis Nilsen – poses a conundrum for people like me who don’t really believe in evil, who veer to the (lack of) nurture end of the spectrum in the nature/nurture debate, because there’s nothing in his impoverished, yet fairly unexceptional Glasgow childhood to account for his depravity.

It is also clear from letters leaked to the press over the years, that Brady belongs to an even smaller subset of multiple murderers – those capable of talking articulately, if disingenuously, about their crimes. Indeed, like the fictional Hannibal Lecter, Brady seems utterly absorbed by the workings of his own mind, on some occasions analysing his motives as if he were his own psycho-therapist, at others glorying in his notoriety, as if he were the hero in his own stage play.

For all these reasons, I was eager to hear him speak at his mental health tribunal. Here was a man who – despite his infamy – had not been seen in public for 25 years. And he wasn’t merely answering (or evading) questions on the logistics of the murders – such as where victim Keith Bennett’s body is buried – he was musing on the fundamental question posed by every serial killer: are they mad or bad? Where once Brady claimed to be mad (in order to instigate a transfer from mainstream Durham Prison to Ashworth secure psychiatric hospital in 1985), he now insisted he was bad (and had feigned his symptoms the first time round).

The problem, as it transpired, was that this was less a serious attempt to investigate how murderers are created and more an opportunity for a narcissist to “grandstand”. As with Norwegian spree killer Anders Breivik – who also sought to be judged sane – he simply craved a platform for his warped ramblings.

There was a perverse logic to some of his most outrageous statements; his insistence that his crimes were less serious than those of political leaders who start wars because they claimed fewer victims is superficially persuasive until you remember Brady targeted children for the sheer thrill of it (and only stopped because he was caught). But others, such as his claim he killed recreationally, were terrifying in their lack of remorse or insight into the damage inflicted on his victims and their extended families.

If the public hearing proved anything, it was that Brady had lost none of his lust for control, revelling in his faith in his own perceived ability to bend everyone from hospital cleaners to consultant psychiatrists to his will. I suppose too it reinforced what many mental health experts have been saying for some time, that what we call “evil” is in fact absence of empathy, combined with an inflated sense of self and a lack of proportionality. In the end, whether this inability to empathise stems from a personality disorder or a treatable mental illness (and whether Brady is incarcerated in Ashworth or a prison) makes no real difference to anyone other than him and those responsible for his care.

Despite the criticism he has faced, I understand why Judge Robert Atherton agreed to Brady’s request to hold the tribunal in public. Allowing Brady to freely express himself means no-one is likely to be in any doubt as to the continuing danger he poses. But on balance, I’d say the decision did more harm than good, affording Brady the opportunity to flaunt his supposed intellectual superiority – boasting about his knowledge of Plato and Shakespeare – without advancing our understanding of his motivation.

This was the first time we’d heard Brady’s voice since his trial in 1968 and I hope it will be the last because, notwithstanding my own enduring interest, obsessing over his crimes is indulgent and unhealthy. By hanging on his every word, we are playing into his hands, feeding his image of himself as the most renowned killer of all time while the suffering of his victims’ few surviving relatives is unabated. After all this time, they have surely earned the right not to hear Brady discuss the killings as if they were some kind of worthy philosophical experiment as opposed to heinous acts of unmitigated savagery.

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1