Dani Garavelli: Jury in crossfire in Duggan case

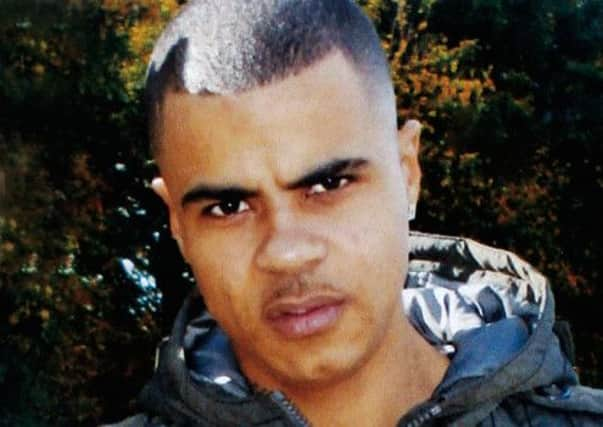

That holds true whether or not the 29-year-old was a member of the feared Tottenham Mandem gang or had collected (and then disposed of) a gun shortly before the police marksman opened fire at him on 4 August, 2011. Still, even taking on board the anger of a community which views the events leading up to his death through the prism of its own experience of prejudice, the manner in which the jury has been vilified for returning a verdict of lawful killing is disgraceful.

It may be difficult for outsiders to understand how officer V53 could have believed Duggan was pointing a firearm when the one civilian witness to the incident said he was raising his arms as if in surrender when he was shot, or for those who loved him to countenance that the gun found in a sock 20 yards away wasn’t planted there by police. However, jurors sat through three months of conflicting evidence in a highly-charged atmosphere and it’s unacceptable to suggest they acted in anything other than good faith.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdImagine how stressful it must have been for these men and women to deliberate, knowing how the streets of London exploded into violence after the killing and how much was riding on their judgment. Do the supporters of Duggan who lambasted them on social media think these jurors are immune to his mother’s pain, the fear of reprisals or guilt that they might have got it wrong? So serious was the threat of intimidation they were granted anonymity and a police escort. No wonder they’ve been offered counselling. In any case, I think that though the verdict is debatable, the scale of the public outrage has been fuelled by a series of misconceptions. There has been a concerted attempt in some quarters to draw parallels between his death and that of Harry Stanley, Jean Charles de Menezes, and Ian Tomlinson, all of whom were unarmed and killed by police officers acting with excessive force and/or on false information. However, you don’t have to be a right-wing reactionary to contend they’re very different in nature. Stanley was shot while carrying the leg of a coffee table; De Menezes was a Brazilian mistaken for a 7/7 bombing suspect; and Tomlinson was a newspaper vendor making his way home during the G20 protests. None of them were known to police or engaged in any wrongdoing. They were random victims who, by a quirk of circumstance and with no justification, were judged to be dangerous.

Whatever the truth as to Duggan’s past – and he was only convicted of minor offences – he was considered a player and was at the centre of a police operation at the time of the killing. Given drugs dealer Kevin Hutchinson-Foster was convicted of supplying a Bruni Olympic pistol to him shortly before his death, it seems likely he was in possession of a firearm while travelling in the mini-cab the police were pursuing, although not at the point at which he was shot.

Now, it’s true that possession of a gun is not proof of intent to use it, and that, like all suspects, Duggan should be have given the chance to surrender to police. But it does mean that – unlike the other cases – there was a degree of validity to both police intelligence and police fears.

Anger has also been fuelled by the unfortunate phrasing of the verdict. Certainly the term “lawful killing” does imply Duggan’s death is being endorsed instead of lamented, and I heard one journalist say the jury had decided the police officer was “right” to open fire on him. This is not accurate. The jurors said only that they believed V53 perceived Duggan as a threat at the time he shot him and responded accordingly. Ruling that his actions fell short of being criminal is a long way from condoning them.

We know there are still many unanswered questions about the way police behaved in the aftermath of the killing. Who told journalists there had been an exchange of fire at the scene? Why did the Independent Police Complaints Commission fail to immediately correct this version of events when it discovered it was inaccurate? Why did officers take so long to visit Duggan’s mother, Pamela?

The conduct of some officers and the IPCC smacks of a cover-up and suggests lessons have not been learned from Hillsborough, Stephen Lawrence and other scandals. It exposes the prejudices which lead to excessive use of stop-and-search and lack of trust within black communities, but fault lies on both sides.

It may well be true, as one social worker has suggested, that it is difficult for young black men in inner city estates to dissociate themselves from gangsters they have grown up with so they gain reputations they do not merit. And that Duggan’s killing has sent out a message that their lives are worthless. But it’s also the case that officers cannot stand by and let gun-toting criminals take pot-shots at each other with the risk that bystanders get caught in the crossfire. It would be wrong to underplay the errors of judgment that led to unarmed man being shot or the attempts to smear him afterwards. But it is just as unhelpful to gloss over the scale of London’s gangland problems.

The truth is that areas such as Tottenham are caught up in a vicious cycle in which discrimination fuels violence which fuels more discrimination. If it is to be broken then both sides need to face up to the part they play in perpetuating it.

• Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1