Covid virus is showing us how evolution works – Professor Eleanor Riley

The first mammals appeared at least 170 million years before the first humans. Skeletons of modern humans are clearly different from those of hominids living 100,000 years ago but significant anatomical differences between Roman Britons and ourselves are harder to find.

The characteristics of modern humans have arisen as the result of innumerable random mutations (coding changes) in our DNA that individually and collectively led to physiological changes which left us better able to thrive in our local environments. An ancestor with mutations that conferred a physiological advantage was more likely to survive and pass their genes to the next generation than someone who lacked these mutations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a stable environment, the survival and procreation advantage conferred by any particular mutation is typically quite small, so the frequency of the mutated gene in the population increases rather slowly, taking many generations to reach noticeable prevalence.

However, when there is an abrupt change in the environment, specific genetic traits may suddenly confer a major advantage and their frequency may increase markedly with each passing generation.

In extreme circumstances, the selective pressures imposed when encountering an entirely new ecosystem can lead to almost immediate disappearance of ill-adapted species and their gradual replacement by better-adapted species.

Whether or not an asteroid impact caused the catastrophic extinction event underlying the demise of non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago, the ecological “niches” that were vacated during the extinction provided the opportunity for an explosive period of evolution and the emergence of myriad new species of plants and animals.

The protracted timescale of human evolution is partly due to our lengthy inter-generational interval and small number of progeny. As a rule, the shorter the time between generations, and the greater the number of surviving offspring, the faster a species can evolve.

A mutation that conferred complete protection against Plasmodium vivax malaria likely took 30,000 years or more to become overwhelmingly dominant among sub-Saharan Africans.

By contrast, in Australia, it took less than 50 years for rabbits (that are sexually mature by six months of age and can produce upward of 150 offspring over their lifespan) to become highly resistant to the myxomatosis virus that was introduced to control their numbers.

At the other end of the spectrum, some bacteria divide every ten minutes in the laboratory; even in their natural environment, bacterial generations are measured in hours rather than days meaning, for example, that resistance to antibiotics can evolve and spread very rapidly in the right conditions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

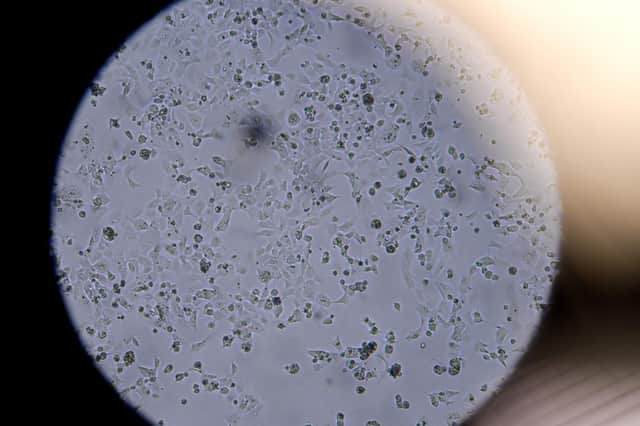

Hide AdWhich brings us to Sars-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. Back in 2019, humans were a completely new niche for Sars-CoV-2 and it was poorly adapted to our cells.

But, each cell it did manage to infect produced 1,000 new viruses. Each of these progeny viruses infected a new cell, multiplying 1,000-fold every 12 hours. Three days after infection, one person could be excreting billions of viruses.

Any virus carrying a mutation making it a better fit for our cells could reproduce faster and its progeny would eventually dominate the population. As the alpha and, now, delta Sars-CoV-2 variants have shown, evolution can sometimes happen before our eyes.

Eleanor Riley is professor of infectious disease immunology at the University of Edinburgh

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.