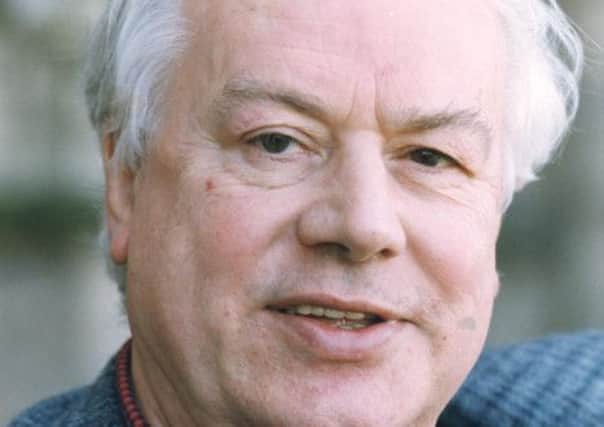

Comment: Tom Nairn: one of Scotland’s great thinkers

As I got older and began to delve into them, I was quietly thrilled to find my dad’s name – Stephen Maxwell – among those cited by Nairn, alongside Gordon Brown and Hamish Henderson, in the acknowledgements. But it wasn’t until my late teens that I actually began to engage with, or even really comprehend, their contents.

The Break-Up of Britain is Nairn’s best-known work. It sets out the ideas that secured his status as the most influential Scottish intellectual of the 20th century. In recent years Nairn has moved away from the Marxism that framed his thinking in the 1960s and 70s, but the nine essays included in Break-Up reflect his initial, “resolutely materialist”, outlook.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor Nairn, the emergence of modern Scottish nationalism is a response to the uneven development of British capitalism and the peculiarly archaic nature of the British state. The concentration of power in London – a product of Britain’s “fossilised” constitutional system – has limited Scotland’s economic potential, leading sections of Scottish society to embrace independence as an escape route from the UK’s post-war crisis and decline.

The contemporary relevance of Nairn’s theory is clear. Support for independence is highest in deprived neighbourhoods, where the corrosive effects of Westminster’s free-market reforms have been felt most sharply. The more imbalanced the UK economy becomes, with an ever-increasing focus on London-based finance as the motor of British growth, the less secure Scotland’s membership of the UK is. Whether in the form of enhanced devolution or outright independence, the “Celtic peripheries” are straining for more economic autonomy – and the UK’s brittle political institutions are struggling to cope with the pressure. Sooner or later, Britain is going to break.

For the sheer rigour and originality of his thought, Nairn is widely acknowledged as a leading political theorist. But he should also be regarded as one of Scotland’s great non-fiction writers. For the past few months, I have been editing, with Pete Ramand of the Radical Independence Campaign, a collection of Nairn’s essays. Old Nations, Auld Enemies, New Times, to be launched on 15 August, covers the full span of Nairn’s work, from his early contributions to the New Left Review, in which he developed a ground-breaking, Gramscian analysis of British political culture, to his more recent examinations of globalisation, the monarchy and the English question.

Earlier this year, we unearthed a series of articles Nairn wrote for Question Magazine, a short-lived political journal from the 1970s. One of them, The New Exiles (1976), describes Nairn’s encounter with some old university friends from England – Jonathan and Susan Barker – who have since relocated to a “remote Inverness-shire glen”. The Barkers, Nairn explains, were “paladins of civilisation … Jonathan’s writing, his research and his teaching had been mainly on Scottish problems”.

The reunion turned sour when Nairn raised the issue of nationalism: “The idyll began to crumble after breakfast. I was curious to know how they viewed devolution, and my very question must have manifested a positive interest in the topic … Jonathan presented me with his many missives to The Scotsman and Herald. It was a deeply depressing moment. A fearful anxiety now corroded their rural bliss. Far from thinking of self-government as a justification of their efforts, they saw sheer disaster. The moving forces behind it were our old enemies – bigotry, football tartantry, Calvinical intolerance.”

The New Exiles is typical of Nairn’s journalism: ironic, autobiographical and evocative. Nairn has the rare ability, as a polemical writer, to empathise with his subjects. In another article, Second-rate Unionism, published in this paper in 1992, Nairn responds to the plaintive claims of Tory foreign secretary Douglas Hurd that devolution will Balkanise the United Kingdom: “Take the broad eastern vista from North Bridge. George Steiner once remarked that the light round there always made him think of the Baltic and St Petersburg. Wouldn’t this effect be stronger if a working Scottish Parliament stood in the foreground of the view? Soon this could be what driving into Edinburgh is like – an idea which fills me with anything but sadness.”

Nairn’s influence has been and remains massive. No other writer has left so deep an impression on mainstream thinking about Scotland, Britain and nationalism. Yet Scotland’s media and academic establishments have never fully embraced him. As a result, Nairn has spent many years working outside Scotland, including in England and Australia, when he might have been here, taking a more prominent role in our national debate.

This is one of the reasons I was so keen to work on Old Nations. People should be more conscious of Nairn’s unique voice now, with 18 September firmly on the horizon, than ever.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd of course it will be hugely rewarding, not to say a little surreal, for me to see a copy of Old Nations sitting alongside The Break-Up of Britain on my dad’s bookshelves. I just hope it does Tom justice.

l Jamie Maxwell is an Edinburgh-based political journalist. He writes for the New Statesman and Bella Caledonia.