Comment: Taking a stand over welfare safety net

Or is he doomed to share the fate of King Canute, powerless to halt a constantly incoming tide?

Ahead of the budget on Wednesday a storm of hostile commentary is brewing on cuts to welfare benefits and tighter controls over public spending that critics insist will prolong “austerity”. There is a fleeting recognition among opponents of the need to bear down on government debt. But could this not be better done by raising taxes on the well-off and spreading the spending cuts over a longer period?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s easy to forget that this week’s Budget is about more than debt control – imperative though that is. It continues to grow, even though the annual budget deficit has been brought down. And the growth in debt needs to be halted if we are to avoid ever more taxpayer billions being absorbed in annual debt interest payments.

The parallel problem is that we have a welfare system that is effectively out of control and in urgent need of reform. The case for action can be summarised in one stark and shocking statistic: more than half of all UK households – 51.5 per cent – now receive more from the state than they pay in taxes.

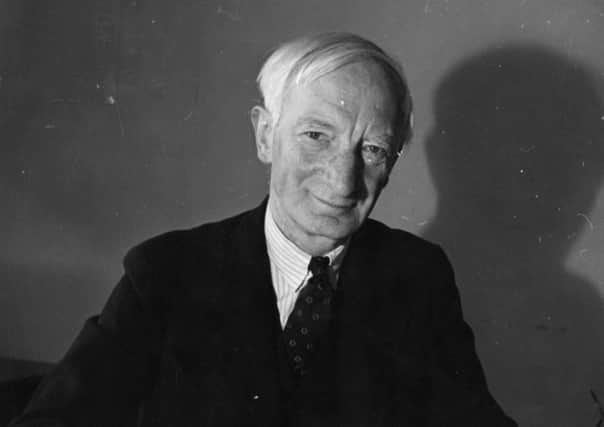

We have come a long way from government welfare provision as envisaged by William Beveridge: a safety net below which the poor could not fall. Help was targeted at those in greatest need.

So how is it that a modern, advanced economy, proudly claiming to be the sixth largest in the world and with the fastest rate of growth in the G7, could have more than half its population as net welfare beneficiaries? How could this possibly be described as a wealthy economy, friendly to enterprise and aspiration?

For decades governments have sought to enlarge and strengthen the welfare safety net. Health spending has risen in real terms, education spending has been protected and benefits widened to cope with the ever changing needs and problems of voters.

But despite the redistributive nature of the tax system and the significant income tax cuts, the poorest households are still paying very high taxes as a proportion of gross income. The richest fifth of households paid £29,200 in tax over 2013/14, which equates to an average tax rate of 34.8 per cent of their gross incomes. The poorest fifth of households paid £4,900 in taxes over the year. Whilst this is much less in absolute terms, at 37.8 per cent, it is proportionately even higher than paid by the richest households. The Budget may do little more than scratch the surface of welfare reform, the furore over £12 billion of mooted welfare savings being more than enough even for a government with a fresh mandate and an overall majority.

But a stand must be made, even one as modest as this. The £12bn figure represents less than 1.7 per cent of the £730bn government annual spending total. Even the £30bn which the Institute for Fiscal Studies reckons will have to be cut from government spending departments to meet the deficit targets by 2018-19 works out at just £7.5bn a year, or barely one per cent of the total.

It hardly seems worth the Chancellor’s decision to revive the Committee of the Commissioners for the Reduction of the National Debt – a group set up to repair the economic damage of the Napoleonic wars – after a lapse of 150 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe problem, however, is less the totality of the savings envisaged than the likelihood that they will come to borne by the most vulnerable – a problem in some part of the government’s own making as it has pledged not to cut pensioner benefits or child benefit. That is why cuts to working tax benefits and housing benefit have found themselves in the front line.

No less problematic is the Chancellor’s new balanced budget rule, set to be showcased again and perhaps defined in more detail on Wednesday. The rule stipulates that in “normal” times governments should run a surplus. But what counts as “normal”? We need to see some more specifics – and a convincing strategy. Successive attempts by governments in the past to achieve, if not a balanced budget then some stability in government borrowing and debt, have been consistently stymied by the impact of external events, flaws in the targeting strategy (such as befell monetary targeting) or a corrosion of political will as the next election approaches.

So why not resort to tax increases instead of letting the whole deficit reduction programme fall on public spending cuts?

The problem here is that government spending and revenue projections rely on economic growth – and tax increases tend to lower growth over time. The overwhelming message of more recent studies is that rises in tax levels reduce the growth rate of economies — in the most authoritative studies, a 10 per cent rise in the overall ratio of tax to GDP is found to be associated with a 0.5%-2.0% fall in the growth rate of GDP.

However, there are several factors that may make the Chancellor’s job a little less daunting and miserablist this week than it all looks. The Office for Budget Responsibility growth forecasts (2.5 per cent for this year and 2.3 per cent next) look cautious and there is greater scope for a cyclical improvement in the deficit.

In addition, the OBR’s full-year forecast of 2.3 per cent for pay growth looks modest given that various metrics are stronger than this and rising (eg average earnings running at 2.7 per cent on the year in April).

This is good news for the Treasury in this respect as income tax inflows are arguably more sensitive to wage levels than corporation tax receipts.

Also, data on the public finances so far this year shows that borrowing is running some £2.6bn per month below year-ago levels. Number crunchers at Investec have said: “The risks to the fiscal outlook now seem to be weighted towards a faster improvement in the deficit, which marks a shift in direction from the majority of the post-crisis years.”

Even so, Osborne will be forced to advance this week under a barrage of withering political fire. Sticking with the plan will remain his greatest single challenge. «