Comment: SNP’s vision for defence lacks firepower

ON ENLISTMENT, those who enter the British armed forces swear to serve “Her Majesty, her heirs and successors”. The SNP has decided that, if Scotland does vote for independence, it will retain the monarchy. In this sense the United Kingdom will continue, not end, and those service personnel who transfer to the Scottish defence force will not necessarily need to commit themselves to a new oath.

Here, as in virtually all aspects of domestic policy, the case for independence now looks little different from that for devo-max. Defence and foreign policy, rightly stressed by many as the defining characteristics of a sovereign state, should be the core of the debate for independence, but even here the convergence of SNP policy with existing practices is almost more evident than any divergence. Most obviously, has been the decision to commit to Nato membership. For the SNP, greater strategic coherence has come at a political price.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

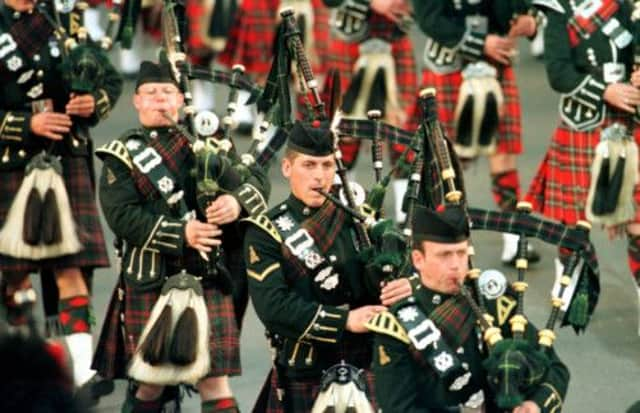

Hide AdThe corollary of this convergence is twofold. First, the SNP has eschewed radicalism in the structure for its proposed defence force. The emphasis has been on what Scotland will inherit from the UK, rather than what it will change. Nowhere is this more evident than in the commitment to “restore” the “historic” Scottish regiments.

Second, and consequently, more general debates about the UK’s defence policy have begun to overlap with those about the defence of Scotland in particular. So far, however, both London and Edinburgh have colluded in keeping them apart. Both have treated the defence of Scotland as an adjunct of the Scottish referendum, not as an independent item.

This point even applies to Trident, the one area of defence policy which has provoked significant debate. In opposing the possession of nuclear weapons, the SNP is joined – according to some reports – by at least some service personnel in the Ministry of Defence. Elements in both Holyrood and Whitehall are aligned, albeit for different reasons.

The SNP’s stance is above all a moral one, a principled opposition to weapons of mass destruction: hence the party’s decision to embrace membership of Nato, whose strategic concept rests on nuclear deterrence, has distanced itself from its roots. The opposition to nuclear weapons in the armed forces is, above all, financial: the constraints which Trident and its possible successor add to an already limited budget no longer represent good value for money.

In 1957, when the UK embraced nuclear deterrence, it did so precisely because it represented a cheaper form of defence for a small state with a weak economy than did mass manpower. That logic might have recommended nuclear weapons to an independent Scotland too.

President Barack Obama’s announcement in January last year that the United States would “pivot” from Europe to the “Asia-Pacific” enhances the case for European powers to possess their own nuclear weapons. For a continent riven by major war since 1914, it can be argued, if not proven, that the threat of nuclear weapons has been a major factor in keeping the peace since 1945. The UK, not just Scotland, needs a proper debate on the deterrent.

If an independent Scotland is in Nato, it will, whether it likes it or not, benefit from the security inherent in being a member of a nuclear alliance. The very notion of the independence of a small state rests on that presumption of more general stability.

In the 19th century, European states were created by amalgamation more than separation, with the result that their combined resources created defensive robustness and military potential. Today’s practice of state generation (and multiplication) by division depends on the protective umbrellas provided by collective organisations like the United Nations and the European Union.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Scottish appetite for Europe, when contrasted with the scepticism south of the Border, for which the rise of Ukip has become the standard-bearer, is another foreign policy debate in which British and Scottish interests should inform each other, rather than be conducted in self-contained compartments.

So Nato membership is an insurance policy to cover defence inadequacy. If that applies to the UK, it will apply even more to an independent Scotland, with forces projected to muster a mere 15,000.

The presumption is that we live in extraordinarily secure times, and that such forces will be used overseas only for humanitarian interventions or peacekeeping. But Nato is underpinned by article five, which states that an attack on one member is an attack on all. Its terms could oblige Scotland to help Turkey if its frontiers were infringed by Syria, or Poland if it were invaded by Russia, or Canada or the US if either were attacked on their Pacific seaboard. It is worth remembering that the only time that Nato has invoked article five was in 2001, in the defence not of a small state, but of a super-power, the US.

If Scotland is serious about defence and sees real benefit in its collective organisation (and those two conditions hang together), then its forces should be shaped not by its “share” of what it inherits from the UK, but by how it can further the common weal.

Rather than haggling over a little bit of this and that, the SNP should think how it will respond to the call of the secretary-general for “smart defence”. It should think about its capacity to contribute “niche” capabilities. Scotland is an archipelago of almost 800 islands, with an established ship-building industry, and with significant maritime commercial interests.

It also has responsibility for the security of its airspace. Its focus should be air-maritime. Here too there is an argument of wider relevance: it cannot afford fast jets, but it could follow the 80 or so states which are already looking to remotely-piloted vehicles and robotic mines. The drones debate is for us as well as the US.

When put in these terms, the case for the Scottish infantry, whose very numbers could swamp the whole defence force structure, looks weak. But even here there can be more radical options than are currently on the table. If the SNP is determined to give fresh life to the cap badges of the past, from the Seaforths to the Gordons, all of them creations as well as casualties of the Union, why is it so wedded to an army modelled on the British regular example? One of its favourite comparators is Norway, a country in which conscription remains the embodiment of national defence.

If national service is a political step too far, should the SNP not at least be looking at an army more weighted to reserves than regulars? A new state is the opportunity for new thinking. In relation to defence the SNP looks more conservative and traditional than its rhetoric suggests.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• Professor Sir Hew Strachan is Professor of the History of War and Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. He will speak at The Scotsman Conferences’ Defence Policy: Protecting Scotland and Preserving Jobs on Friday, 14 June: www.scotsmsanconferences.com