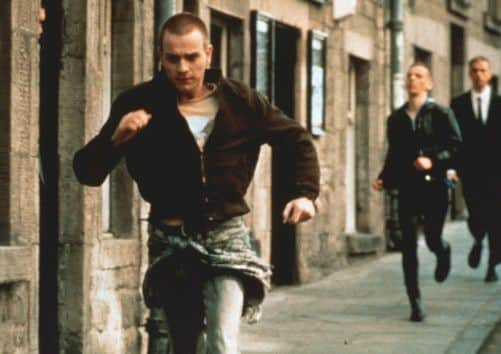

Comment: Choose Trainspotting as best Scots novel

‘Whaur’s yer Wullie Shakespeare noo?” was famously and triumphantly shouted in Edinburgh at an early performance of John Home’s 18th century play Douglas. Well, today Edinburgh should be shouting “Whaur’s yer Grassic Gibbon noo?” for it is surely clear now that Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting is the greatest Scottish novel of the 20th century.

Too early to call it a classic? Actually, it was published 20 years ago. A point brought home to me when Welsh retweeted Simon Blackwell, the brilliant comedy writer/producer with Peep Show and The Thick of It and under his belt, saying: “20 years since I did my first bit of paid writing – reviewing @WelshIrvine’s Trainspotting for the Literary Review, and interviewing him.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe book is like that: an event in your life that feels like an event in history – such as seeing the Subway Sect at the Playhouse, Edinburgh, in 1977; a moment when you realise there are new possibilities.

In 1993, I’d been living away from Edinburgh for nearly a decade. One day, I was browsing in a bookshop in London. Serendipity is one of the greatest things in life and one of the true pleasures of bookshops. Stumbling on Irvine Welsh’s novel was one of my great finds. I remember it was the size and design of the book that first drew my attention. A Secker & Warburg paperback, but in a chunky, continental format with a stiffer than normal cover that was folded like a dust-jacket. I took it from the shelf. Nice restrained design, good cover. And a new Scottish author. I opened the book and read. In minutes, I knew that I was buying it and making my friends read it, too. Why? It was an Edinburgh novel. But more than that, it was written in Scots – not just any form of Scots, but Edinburgh Scots.

Scottish literature is part of me. I remember my first primary school headteacher as a kindly gent who would send us home – the whole school – on days that it rained. His actions were not family-friendly, but they were definitely child-friendly. He lived near us in the Greenbank area of Edinburgh, and was called Forbes MacGregor. Years later, I realised he was a combatant in the Scottish literary renaissance whose Gowks of Mowdieknowes was a not bad satire of those who dived head first into the Scottish national dictionary and cam oot as makars.

At secondary school, the head of English was Charles King, whose anthology Twelve Modern Scottish Poets probably gave more young Scots access to our heritage than almost any other intervention. As a teenager reading Muir, MacDiarmid, Soutar, Garioch, MacCaig, Sydney Goodsir Smith, Edwin Morgan, George Mackay Brown, Iain Crichton Smith and the others was more than a foundation, it was a privilege. But, when we are young we don’t see it that way.

Mr King brought Norman MacCaig to the school to read – still one of the greatest live performances of my life. He knew them – knew them all. He drank with them, and gossiped. And, to be honest, we didn’t listen – or not enough, not fully.

At the University of Edinburgh, I studied Scottish literature under the austere, but brilliant, Professor John McQueen, whose Ballatis of Lufe – medieval and early Renaissance Scottish poetry – should be sought out and bought immediately (my copy comes from a shop in Gaillac in southern France).

Which is all to say, that Welsh, whatever his roots in music – from speed-inflected punk to ecstasy-influenced dance – is from a literary tradition, a culture. And, for myself, what blew me away was the accuracy of writing just like we speak in Edinburgh.

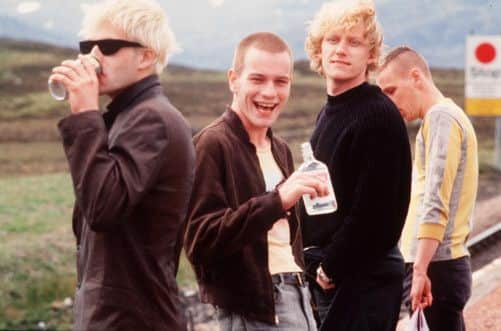

I love Hugh MacDiarmid this side of idolatry and I have been a fan of James Kelman since Not Not While The Giro, but the Doric, literary Lallans and west coast Scots were not what I grew up with. It is different in Edinburgh. The world of “coupon”, “radge”, “stoorie”, “barry” and “chory” was my world. One skim through Trainspotting and I was sold. This was Edinburgh; the one I grew up in, the one my brothers and sisters still lived in. It was as mental as Glasgow. And as real as my secondary school. I knew a Begbie – we all know a Begbie, don’t we? He is the violence that simmers between men in Edinburgh pubs. The guy you knew in school who’d have your back because you’d helped him in the physics class, or you were in the same primary school football team, or he was your pal’s pal. On a hair-trigger, but not with you.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd it was a modern Edinburgh. I am a huge fan of Muriel Spark, in my view she is the greatest novelist of the post-war period (in English literature that is). But it is her work as a whole that is great.The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, which is set in Edinburgh in the inter-war years is in a way the best Scottish nouveau roman’ though the late-lamented Giles Gordon comes a close second with Girl with Red Hair (buy it too, read it).

Leith has always been Edinburgh’s deniable, dirty little secret, even though it has been part of Edinburgh since the 1930s. What Welsh did was reveal the truth of a part of Edinburgh: the heroin, the life of the addict, the reason that we became the Aids capital of Europe – the dark background, in truth, against which the successes of the Festival, the Fringe, the financial services sector banks gained definition.

For me, for the publication of Trainspotting in 1993 was like the first performance of The Rite of Spring in 1913 in Paris. There was a moment before and a moment after – but the world changed forever. There is Scotland before and there is Scotland after.

When the banks – our banks, Royal Bank of Scotland and HBOS – blew up and nearly broke the world, how prescient was Welsh? “Choose Life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a f****** big television, choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players and electrical tin openers … Choose your future. Choose life … But why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life. I chose somethin’ else.”

What is that something else? We’re still asking. It’s not heroin, but nor is it turbo-charged capitalism. Welsh posed the questions well before the crisis. That we still struggle with the answers shows what a great artist he is.