Brian Monteith: Giving up Britishness

Tomorrow sees the return to Edinburgh of a terrific export from Scotland, as the Traverse brings us The Confessions of Gordon Brown, written by Edinburgh’s own Kevin Toolis. A huge hit at last year’s Edinburgh Fringe and going on to great acclaim in London’s West End, it is an examination of the nature of leadership in politics.

The strengths and weaknesses of Gordon Brown’s psyche that placed him in No.10 and then lost him his tenure are worthy of examination while it is all still fresh in our minds. The reflection of years of scheming – that were as much the reason he got there as the explanation of why the removal men came in 2010 – make for a Shakespearean tragedy about a desire for power that was unrequited by the British people.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

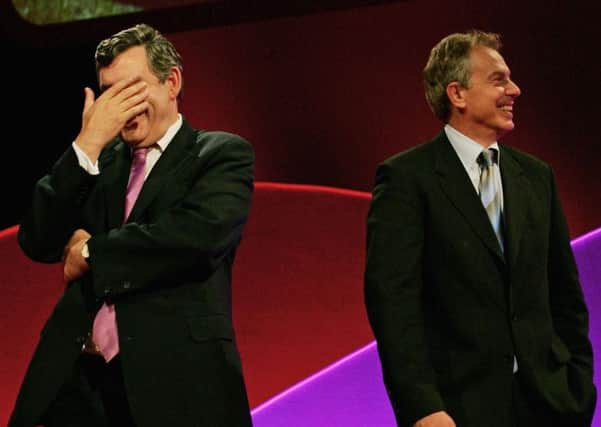

Hide AdCorrection, by mostly England; for in Scotland the Labour percentages actually improved in his election defeat. Brown, a son of the manse from Kirkcaldy, was just never accepted by English voters in the same way that Edinburgh-born and educated Tony Blair was.

If they both had, to varying degrees, a Scottish background, what could the reason be? Being at the wrong end of a fading Labour hegemony? But Brown could have gone to the country earlier – and in all probability could have won. Was it being a dour Scot as opposed to a hope-inspiring great communicator like Blair? Toolis certainly argues that hope is a true mark of effective, winning leadership.

This suggests to me that the next play Toolis should be working on is A Year In The Life of Alexander Salmond, written after the referendum result, so he can consider all the twists and turns that have passed already – and are still yet to come. Will the “hope” that the First Minister offers show true leadership qualities, will he take us on the road to Damascus? Or is the man setting himself up to be immolated on a funeral pyre of his own hubris? It would be some inferno.

The Confessions of Gordon Brown is written by a Scot, about a Scot, staged throughout Scotland and yet is undoubtedly a thoroughly British drama. It is not parochial in any way, it is not The Confessions of Jack McConnell, or Secret Diary of Nicola Sturgeon aged 13¾. Toolis examines big issues for a British audience about British politics because he has a locus. Toolis is not only Scottish, he is British too.

I have said it before, and I believe it bears repeating even though it is tongue-in-cheek: why should Scots settle for running Scotland when we can run Britain too? We have in the past, we do still in various fields – and we can continue to do so in so many ways.

Being part of the union that is the United Kingdom gives our writers – as it gives our actors, directors, impresarios, musicians and technicians – a larger stage to play on. That is not to say the stage would not exist if Scotland were independent, of course it would, just as it exists now for Irish dramatists and actors – but the relationship would become entirely different, it would change.

Armando Iannucci is another example of a successful Scot, this time from Glasgow with Italian genes. His satirical writing is caustic, memorable and influential, catching the Blairite spin-doctoring zeitgeist and exposing it for all its crass, ends-justifies-the-means amorality. But, like Toolis, Iannucci has a locus: he is not just Scottish but British too.

Rory Bremner, another Edinburgh-born and raised Scot, needs no introduction for his excoriating portrayals of British politicians. Again he has a locus that gives him a credibility that would be different, and maybe not exist at all, if he had been a foreigner.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCalling Toolis, Iannucci and Bremner foreigners in what is currently their own land might seem jarring, a gross misrepresentation, but in a future where Scotland is independent, such writers and performers would become just that. Unless such emigrants had forsaken their own land and identity to become British, not Scottish, how could British political society, now only composed of England, Wales and Northern Ireland, consider them anything else?

How well would such necessarily critical writing and drama be received by the British public from people coming from a country that had rejected the solidarity of sharing the highs and lows of common experience? It might not happen overnight, but instead of having access to a bigger stage and being accepted as equals to say what we want about our own country, we would become onlookers.

I have no knowledge of how Scottish writers such as Toolis, Iannucci and Bremner will vote in the coming referendum. Chances are, one or all of them might not have a vote at all, as they are doing what many Scots do – spending a great deal of time in London, capital of their country, the United Kingdom, where the vast majority of dramatic productions are commissioned, cast and produced. This makes them no less Scottish, but the referendum outcome could remove their identity of being British.

Many nationalists argue against this, saying we shall all remain British whatever the outcome, but, like deciding on whether or not there will be a formal currency union, being considered British would not be for Scotland alone to decide. People from the Republic of Ireland are not generally considered British by people in the UK and if any Irishman seeks such a description I have yet to meet one.

Scottish identity will go the same way, from being Scottish and British to being only Scottish. Some will not lament this fact, but I certainly shall and I know I am not alone. In rejecting our family, the relationships and opportunities would inevitably change.

The coming referendum is not, then, just about the governance system of Scotland. It is about identity, too. Whether one works in Glasgow, Edinburgh or London, one can be Scottish and British at one and the same time and use that to your advantage. After 18 September, we could find we have given up on being British – while those that remain so will be very aware of this rejection. That’s not what I call hope.