Booker Prize: The Shadow King is the pick of the shortlist for me – Laura Waddell

Somehow I have read the Booker shortlist in entirety again. I never set out to, but the slippery slope to completing the set starts with one that sounds particularly appealing, followed by a second already in my pile. Here are my findings.

There are four debut authors among the six, overshadowed by headines aghast at Hilary Mantel’s omission. Not only is this insulting to the shortlisted authors, but frustrating for the reader – please, give us the list first, analysis afterwards.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf the thousands of novelists debuting each year, very few are plucked for Booker stardom. The downside of stratospheric career boost is a level of critique far harsher than early career peers face; a notable example is Sally Rooney.

Those who worried American authors would skew the odds have had fears realised. Four shortlistees are American residents. And as the NY Times reported on Tuesday evening, the winner announcement has been moved to avoid Barack Obama’s memoir, a certain sales-chart juggernaut. Nobody in the book industry likes a clash, competing for press and retail spotlighting, but the move signifies how the American literary landscape is shaping this British book prize’s direction.

Meanwhile, American spelling lurked in at least three books not translated into British English for their UK editions (the first giveaway often the word ‘color’.) Tut tut.

But three American authors write of other places – Ethiopia, India, and Scotland. This lends the list the touch of globalism more usually felt in the Booker International, which awards translated fiction. A variety of settings breaks up American and UK navel-gazing; references, cultural and historical, are wider-ranging. Zimbabwean Tsitsi Dangarembga’s shortlisting was announced on a Tuesday; on the Friday, she was in court following a protest against government corruption.

Another talking point was judge Emily Wilson’s suggestion of reading “blind”. It might make plausible deniability easier in a small professional world, but surely anyone well read enough to be a Booker judge would recognise idiosyncratic styles. More crucially though, shouldn’t judges be trusted to have, and pride themselves on, integrity? It’s not necessarily the list I would have chosen, but I don’t begrudge the judges their preferences.

I warmed to young Agnes of eco-crisis thriller The New Wilderness by Diane Cook, learning her craft as a trail leader. A band of citizens are permitted to live in the only remaining undeveloped land, moved on by rangers. But tension between old and new residents and the ‘right’ to be there could have been explored more deeply and earlier.

Real Life by Brandon Taylor tells the story of Wallace, a gay black man studying biosciences at a Southern university, and his extended circle of friends which reminded me of the attractive, educated quartet in Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. Stuggling after his father’s death and experiencing racist aggressions at the lab, it is a fresh perspective on the typical American campus novel. But I wished for more of Wallace’s inner life, and the pacing dragged, lingering on each scene.

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi is set in Pune, India, charting the fraught relationship between adult daughter and neglectful mother now requiring full-time care. The fiery story of memory and resentment opens with a shiver of Ferrante in the line “I would be lying if I said my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

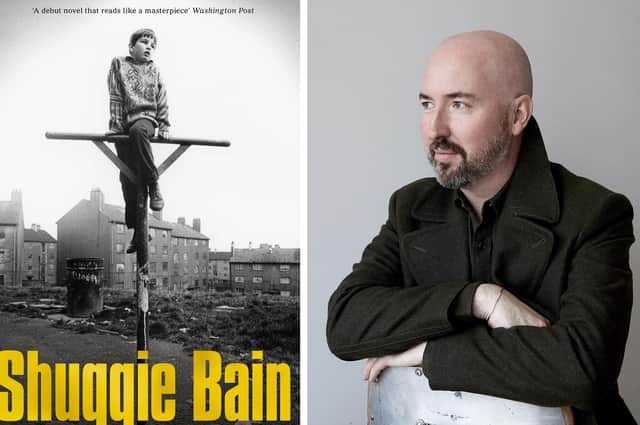

Hide AdWith apologies to Picador’s designers, I wouldn’t have picked up Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart if not shortlisted. While the book is set in the 1980/90s, it looks like it was published then, with a hint of Angela’s Ashes but mostly reminiscent of the forlorn Scottish section in Glasgow Airport’s WH Smith, stocked with the miserable, outdated gangland pulp that makes contemporary Scottish publishers shudder.

But the book turns out to be a rich, sensory depiction of working-class hardship, set in council houses, bedsits and high rises. It’s a Glasgow of night and day, of drunks and pretty girls stumbling out at closing time and waking up with headaches on rain-streaked afternoons. The casual racism and sexism, although era authentic, could have been pared back, but the characters feel lived in. I felt the warmth of a Calor gas fire and the hiss of hairspray. Shuggie, a boy described as “not quite right”, and his troubled, alcoholic mother linger long in the imagination.

Similarly, I have thought often of the excellent This Mournable Body by Tsitsi Dangarembga. Set in post-independence 90s Zimbabwe, Tambu wears “Lady Di” shoes to job interiews and tries to bridge the gap between her aspirations and options, with poor mental health and a backdrop of rife sexual violence. She takes a job in ecotourism, forced to balance opportunity with exploitation. It is a vibrant portrait of survival in an evolving economic state.

Either This Mournable Body or Shuggie Bain would make a worthy winner, but the book that most wowed me was The Shadow King by Maaza Mengiste.

Set in 1935 Ethiopia, it’s an account of women who joined the war against invading colonial power Italy, as fascism was rising in Europe. Mengiste has the gift of embedding a pain and rage much bigger and older than the characters, like determined, dignified Hirut. In one exceptional chapter, a fictionalised Emperor Haile Selassie listens to Verdi’s opera Aida while dreading a losing battle. It is a powerful, accomplished book, a testament to inner strength, and would be my winner.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

The dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. Visit www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Subscribe to the Edinburgh Evening News online and enjoy unlimited access to trusted, fact-checked news and sport from Edinburgh and the Lothians. Visit www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.