Better communicators make a better society

AS the world looks on, what will it say about how we involve and include all citizens in the major events of 2014?

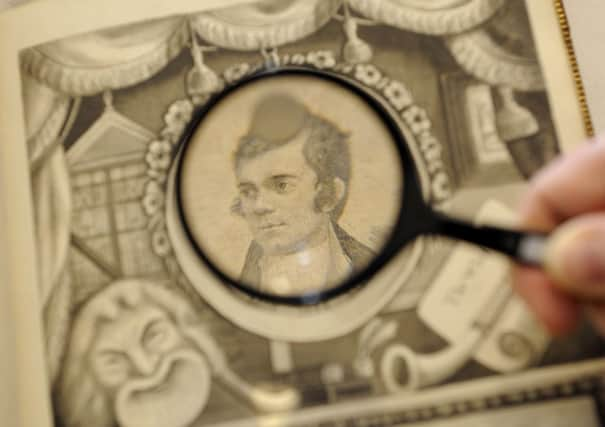

If Robert Burns could observe, what might he say about how we include people not only in major sporting and cultural events and the independence referendum, but also in decisions affecting their own lives and communities?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn particular, how do we reach out to connect with people who communicate in different ways? People who perhaps speak or sign a different language, but more likely people with communication support needs arising from physical or sensory impairments, health issues or learning difficulties?

Imagine how this range of people, all of whom could be living somewhere in Scotland, might see our attempts to reach out and connect with them? Our neighbour who has recently had a stroke; the young child with autism living in the flat below; the deaf teenager wanting to join our village youth group; the chairperson of our tenants’ association who has become hard of hearing; the diner trying to read our menu; the deaf-blind person wanting information about council services; the voter with learning difficulties wanting information about candidates; our friend who tires easily because of major illness; the man at the checkout who stammers.

In “To a Louse”, Burns asks us “to see oursels as others see us” How might we all shape up as communication partners from the perspective of those people? Would we be seen as lousy communicators? Surely if we did, change would be unavoidable.

Scotland has already made significant changes in realising an ambition to be “an inclusive communication nation” and we should feel proud of that. However, there is still some way to go. Individuals and organisations will often have the best of intentions, but Burns’s wise words remind us “The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley.” Intentions are not sufficient to change practice. More action is still required.

I often wonder if we are sometimes paralysed into inaction through our own self-invented fears about inclusive communication (“I wouldn’t know where to start”; “I feel embarrassed”; “I’ll be criticised if I get it wrong”). Burns draws attention in “The Twa Dogs” to this tendency for humans to invent problems: “when nae real ills perplex them, They make enow themsels to vex them.”

We can remove these fears by engaging with the wealth of individuals and organisations who provide advice across a wide range of communication support needs in a supportive, encouraging way that empowers everyone to make changes.

However, it is always we as individuals who need to make changes, since communication impairments exist at the meeting place between people and, after all, organisations are simply made up of people. We can foster a number of key attitudes. A good first step, for example, is always to make an attempt to communicate with another person, however complex you imagine that to be. “Keep on trying” is a key principle of inclusive communication.

Inspired by Burns’s views on equality, we can trust that all people in communication partnerships are equal. Everyone has an equal amount to give, to share and to learn from each other. Indeed, this is where the real power of connection exists, because when we connect with another person we reveal new capacities not just in them but in ourselves. The neighbour who had the stroke encourages us to tell stories that make her laugh. The young child with autism helps us to appreciate the world anew. The deaf teenager encourages us to learn sign language. The tenants’ association makes better decisions because the chairperson is still present. We learn to match our communication attempts with the communication support needs of the customer at the checkout, the diner in the restaurant and the voter on the doorstep. The council earns the reputation of having excellent accessible information on all their services. Engaging with people who communicate in different ways from us allows us to listen to new stories, to belong to more groups, to learn new skills; in doing so we reveal our full capacities and creative gifts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo as we travel together through this historic year, let us ask ourselves if we are fully and meaningfully involving people in the personal decisions that impact on their day-to-day lives, the local decisions that affect their neighbourhoods and communities and the national decisions that Scotland will make. Only when we answer yes to all of these questions, can we call ourselves a nation that is truly inclusive.

• Dr Paul Hart is head of research and practice at Sense Scotland. See also www.sensescotland.org.uk

SEE ALSO