Ashley Davies: The rural dream of farmers’ markets

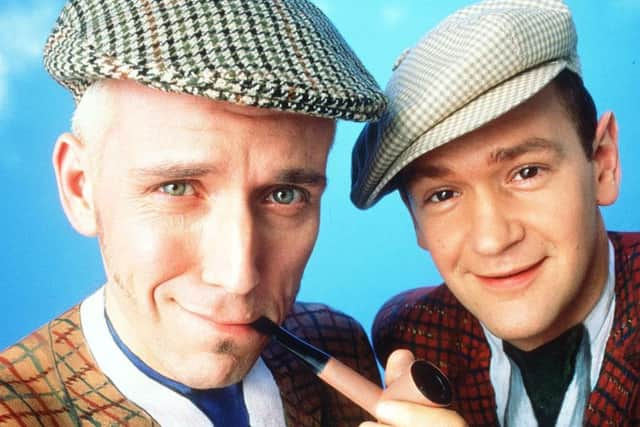

A FEW years ago comedy duo Armstrong and Miller made a very funny sketch about farmers’ markets. It began with a posh man tantalisingly telling a posh woman who’d just been to the supermarket: “I know a place where you can get tomatoes just like that for three times the price.” Impressed and intrigued, she follows him into the ensuing musical number, which lampoons the mustard corduroy-wearing middle classes so dazzled by cynical stallholders who sprinkle muck and feathers on bog-standard produce in order to make it look organic and flog it for a premium.

Such behaviour would obviously never be tolerated in Scotland, but there is definitely a growing appetite for a certain type of outdoor retail environment. Last weekend the much-loved market that operates in Edinburgh’s Stockbridge on Sundays set up camp near the Shore in Leith, and it went down a treat. You can buy wholesome fruit and veg, all manner of interesting sauces, olives, cakes and other nibbly treats, home-made lemonade, seafood, ethically farmed meat, heavenly smelling soap and a cute range of knick-knacks produced by warm-hearted craftspeople.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are also a few stalls selling quality nosh for hungry shoppers. The atmosphere, like that of the occasional offering on Grassmarket, the Saturday farmers’ market on Castle Terrace, or Glasgow’s monthly Mansfield Park (and probably any of the many others listed at scottishfarmersmarkets.co.uk), is gentle and friendly and you’re always rewarded with a mildly smug feeling about buying direct from the producer and bypassing those greedy supermarkets.

On top of this, one should always embrace the opportunity to master the earnest “I’m really thinking about the flavours in this cheese sample you’ve just given me and fully intend to respond to your generosity with a purchase” facial expression, when what you’re really thinking is: “Free food! Get in!”

What bothers me is that most of the food markets we have access to are really just for treats – unless you count artisan marshmallows or ostrich burgers as necessities, in which case you may well have one of those blood diseases associated with royal lineage. Sure, these retail arrangements make you feel like you’re on holiday, piling luscious produce into your bike basket or a canvas bag that broadcasts your green credentials, but, despite not being wildly overpriced, the costs do exclude most normal folk. Hardly anyone will be getting their weekly basics here.

In the hour or so we spent at the Leith market, wolfing down spicy polenta goulash, admiring the inventiveness of twitchy-nosed dogs, and musing about how the whole set-up was unlikely to be under-represented on Instagram, we didn’t hear a single Leith accent. We were in a middle-class, organic venison-scented bubble.

All over the UK there are static and travelling markets, open-air and covered, that bring normal, day-to-day stuff to normal, day-to-day people –places where hard-grafting, big-handed men shout: “All that banana – one pound” and where the weighing and bagging of goods comes with a gratis, harmless wink to be washed down with a small measure of oft-repeated banter.

These markets are cheaper than the chainstores, and the stallholders all know the price and value of everything they peddle.

I visited one such market a few weeks ago in Cambridgeshire, and was actually moved by how comprehensive it was. There was good quality, seasonal – but by no means rare or fancy – fruit and veg at competitive prices; a woman whose stall was festooned with all manner of knickers, from voluminous, billowing bloomers to tiny nylon articles; and a man trading in a creative array of dog treats, including a box full of familiar-shaped bones labelled “postmen’s legs”. The queue for cheap asparagus almost went around the block, and you could buy a decent pair of curtains for the price of family trip to the cinema. There was even a guy selling balaclavas.

There’s nothing like going to the Continent – or indeed, pretty much any other country – to make you feel truly envious about the market culture, where nearly all shoppers are buying ingredients for the meals being cooked that day. It’s a world away from our big weekly shop, which involves us stocking up on stuff that’s only “fresh” because it’s been slowly ripening in refrigerated conditions and is only affordable because the growers have had the fight sucked out of them by retail giants whose main responsibility is to their shareholders.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRealistically, there are several reasons we’re stuck in this situation. Obviously, we are hamstrung by our climate, and if we only ate seasonal, locally produced goods we’d be miserable as hell, sucking on beige root vegetables during the bleakest times of the year. And there’s probably also a correlation between the success of mid-range daily markets and higher levels of, for want of a better word, housewifery.

I’d hazard a guess that most of the food being bought at those markets is being picked up by women who work in the home, rather than in paid employment (or people for whom a siesta is a basic human right). The nine-to-fivers have no option but to go to the supermarket, when most of the stallholders are long gone.

Low-to-mid-range markets on the Continent, as well as in the UK, are increasingly threatened by the growing popularity of retailers like Aldi and Lidl. As a consequence, I do worry that market offerings are becoming increasingly polarised, as they are in cities like London, where you often have to choose between a place that sells knock-off DVDs and 1,000 Biros for a fiver and one where a smug foodie would happily hand over £10 for a kiwano, or whatever the impossibly glamorous food bloggers are hailing as this month’s superfood of choice.

Perhaps a workable solution here would be some kind of a travelling mini-market, where normal foodstuffs are sold by market traders outside areas with high densities of office workers. I’d be up for that; I’d even plan for that if I knew on which days they were coming.

Or perhaps it’s time to just give up the romantic notion that mid-range markets are an important or desirable part of life.

Or maybe towns and cities simply get the markets they deserve.