Allan Massie: We have reason to be grateful

For many in Britain, the Second World War ended with the German surrender in May. The war against Japan had always taken second billing, understandably, since it was far away; no invasion was threatened, and no Japanese bombers flew over London. The soldiers of the 14th Army, fighting in Burma under the command of General, later Field-Marshal, Slim, called themselves “the Forgotten Army”.

In our family it was different. My father and his brother George, rubber planters in Malaya, then serving in the Johore Volunteers, had been taken prisoner in Singapore. They spent the rest of the war in POW camps in Thailand (then usually known as Siam), ill-fed and overworked. My father came close to death. As children, we scarcely knew anything about this, learned, as young children do, to live unthinkingly, scarcely aware of his absence. I can only imagine what it was like for our mother and grandmother.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo when Japan surrendered and the prime minister, Clement Attlee, declared “the last of our enemies has been laid low”, their joy and relief was enormous. Even so, it must for some time – days or weeks, I don’t know – have been mixed with anxiety. The war was over but they didn’t know if Sandy and George were still alive. Anything might have happened in the last weeks and days of the war, and indeed PoWs had been put to work digging graves. And several thousand American, British and Australian PoWs were indeed murdered in Borneo.

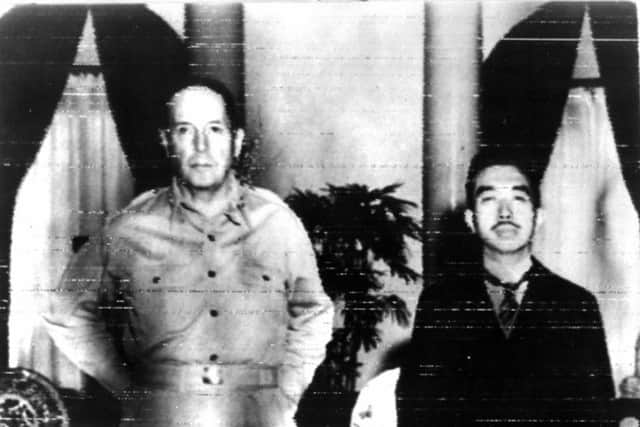

As we all know, the Japanese surrender was precipitated by the dropping of the atom bomb, first on Hiroshima on 6 August, and then on Nagasaki, three days later. This led the emperor, Hirohito, to broadcast to the nation, announcing that the Japanese would agree to the unconditional surrender demanded by the Allies at the conference held at Potsdam in Germany. Japan had previously indicated that it was ready to talk peace, but not to surrender unconditionally. The dropping of the bombs and the Soviet Union’s last-minute engagement in the war in Manchuria on the Allied side settled the matter.

Even at the time there was argument about the morality of using such a terrible weapon. The Scots-born historian Denis Brogan later wrote that he had been at a lunch party in Washington when the news of Hiroshima broke, and that he was the only member of the party who approved of the use of the atom bomb. (My memory is that he later thought he had been wrong.)

That argument has never ended. Seventy years on it still rages. For many today, possibly a majority here in Britain, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were war crimes. Few are still willing to buy the argument that more lives were saved than were lost because the use of the bombs ended the war without an invasion of Japan itself, with the terrible casualties that would have ensued. It’s an argument that goes round in circles. One thing I am sure of. Very few of those who had fathers, sons, husbands or brothers in Japanese camps felt anything but relief when the dropping of the bombs led to the almost immediate Japanese surrender. How do you weigh personal interest against public morality? You may fairly call the use of the atom bomb a war crime or atrocity. But for that atrocity, I might never have known my father.

Some now assert that the atom bomb was dropped as a demonstration of American might to impress and alarm the Soviet Union. They see it as the first act of the Cold War. No doubt the value of impressing the Russians was in some people’s minds, but the Cold War was still some way distant. At Potsdam the new American President Harry Truman thought Stalin a bit like his old political mentor in Missouri, T.J “Boss” Prendergast, a man he could do business with. After the Japanese surrender, the USA hurried to return to a peace-time economy, putting demobilisation and disarmament in train.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki were horrible beyond belief. We may all agree on this now. Britain had worked with the USA on the development of the atom bomb, and had approved its use. Nevertheless one immediate consequence before the creation of Nato (the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) in 1949 was that the Labour government determined that Britain must have its own nuclear weapon, its own deterrent. The Soviet Union had of course already come to a like conclusion: and so the nuclear stand-off was in place. The Cold War lasted for decades. But the deterrent worked. MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) saw to that.

War is hell, and the wars against Germany and Japan were truly infernal, so much so that ending them with a demonstration of the ultimate horror of the nuclear annihilation of two cities may even seem appropriate, sending a message to the world that the worst that can be imagined is within our power to make real. Every war of course has its share of horrors. This is evident in Syria and Iraq today. But nothing has matched the horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and that peculiar horror has not been repeated in the seventy years since. We – mankind – saw what we are capable of, and drew back in fear. The monstrous weapons we possess – weapons even more terrible than the bombs dropped on Japan – have never been used. And yet no country that possesses nuclear weapons has dared to get rid of them.

One Saturday we commemorate VJ Day, the Japanese surrender and the end of the most terrible of wars. The surviving veterans are very old. My father lived to die in his bed, an old man. He never forgave the Japanese for their treatment of their PoWs. Perhaps he should have, but he couldn’t; even in extreme old age he still had nightmares. The war was ended with what one must, I fear, regard as an unspeakable atrocity, a war crime. I should regret it, but I can’t. Nor, I guess, can many whose fathers suffered in Japanese camps and survived because the bombs were dropped.