Alf Young: Power about more than mechanics

To realise Scotland’s huge potential, he told his audience, “we have to have more of the levers of economic power”. Ah, those fabled levers. The ones every ambitious politician aspires to get their hands on, to turn promises into reality.

It’s a resolutely mechanical view of where economic power lies. It conjures up images of those with political power pushing pedals, fiddling with dials and tweaking taps to transmit their intent across their economic domain. Cables tighten. Wires hum. Juices flow. And, out the other end of the machinery of government, come more thriving businesses, more well-paid jobs and rising prosperity for all. Heath Robinson must have captured the whole majesty of it, in print, somewhere.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the great illustrator died in 1944. Seven decades on, we live in markedly different times. Market capitalism reigns supreme. Even when it pushes the self-destruct button, as with the banks in 2008, governments and their taxpayers meekly pick up the tab. The process of empire-building by states has unravelled since the Second World War. That of transnational corporations extending their reach into every corner of our lives, from retail therapy to welfare entitlement, is in full swing.

What we have learned to call globalisation feeds our need for fresh strawberries, or roses, every month of the year, or jeans for under a tenner, even when the real price can be either added drought in Africa, or more than a thousand dead in a collapsed slum factory in Dhaka. And the big beasts building global empires – the Apples, Amazons, Googles, Starbucks and Vodafones of our world – can pick and choose where they pay tax on their profits, regardless of where these surpluses are actually realised.

This week, Tim Cook of Apple went before a US Senate committee, accused of deploying a corporate structure globally that represents the “Holy Grail of tax avoidance”. It’s well known Apple has a cash pile of $145bn (£96bn), most of it held outside the US. One subsidiary, Apple’s Irish-based international sale arm, has generated $74bn in profits but is said “to have paid little or no income taxes to any national government on the vast bulk of these funds”.

Apple, even when its share price is on the slide, is so reluctant to repatriate taxable cash to fund a shareholder dividend, that last month it went into the markets, for the first time in nearly two decades, to raise £17bn from a corporate bond issue at a rock-bottom rate.

While Cook was being berated in Washington, Google’s executive chairman Eric Schmidt was in Hertfordshire, where Ed Miliband ventured on the internet search giant’s turf to say how “deeply disappointed” he was that Google managed to pay just £6m in corporation tax in 2011 on UK sales of £3.2bn. Like Apple, Google books most of those sales in lower-tax Ireland. Schmidt insisted Google simply follows “the tax laws of the countries we operate in”.

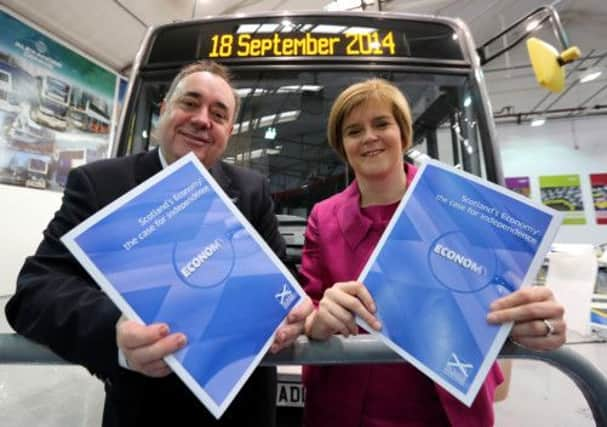

Alexander Dennis Limited (ADL), where Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon launched their economic vision, is currently the fastest growing bus and coach manufacturer in Western Europe, with a growing presence in North America, Asia and Australasia. It employs 2000 people, 900 of them in the village of Camelon, near Falkirk. It’s a Scottish success story. But it has a very long way to go before it has the global commercial clout of an Apple or a Google.

Introducing the First Minister and his deputy to some of its workforce, ADL’s corporate affairs director, Bill Simpson, said: “They’re on a journey to globalise their business, Scotland. So it’s no surprise they’re visiting ADL to see how it’s done.” But, as Bill knows only too well, the full story of what the Alexander side of that business has been through is a very chequered one. Forget levers and learning from each other. This is a story where political power and commercial ambition have frequently been at odds with one another.

Walter Alexander, its founder, was a fitter in a local foundry who, in 1902, opened a small cycle shop in his spare time. In 1913, he launched his own motor service, bussing workers between Falkirk and Grangemouth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1924, he decided to start building buses too. When the big railway companies started to move into bus operations in the late 1920s, Walter and his son, also Walter, found themselves at the wheel of a burgeoning joint venture.

Their growing commercial clout flowed through to their coach building business. Alexander gave the public many innovative buses like the Bluebird, introduced in 1934. But things changed again after 1945, when Atlee’s Labour government decided to nationalise bus services. The Alexander family focused all their efforts on building buses, not running them. In 1969, they bought out a rival in Belfast and started building buses there too.

By the mid-seventies they had started selling buses to the Far East. By 1983, Walter Alexander & Co (Coachbuilders) was the largest supplier of double decker bus bodies in the world. In 1987, the Alexander family decided to float the business on the stock exchange. But by 1990 they had sold their interest. A short-lived management buy-out followed. But by 1995, Alexander was bought by Mayflower Corporation, an English company that already owned rival bus maker Dennis.

By 2001, Mayflower had also acquired another rival, Plaxton, and had consolidated all three bus builders into TransBus International. But by 2004, the Mayflower Group was put into administration and TransBus suffered the same fate. Plaxton was sold back to its management while the assets of Alexander and Dennis were acquired by a group of Scottish investors, led by Brian Souter, Sir Angus Grossart and David Murray.

Souter, now Sir Brian, made the money that enabled him to invest in ADL through another act of political power, the decision of the Thatcher government in 1986 to reverse Atlee’s nationalisation and de-regulate the UK bus industry again. That enabled Sir Brian and his sister, Ann Gloag, to create the Stagecoach bus and rail empire.

Intriguingly, this week also saw shares in Stagecoach’s great Scottish rival, FirstGroup, plunge 30 per cent when it scrapped its dividend and spooked investors with a £615m rights issue.

Its chairman also resigned, taking some of the rap for a whopping debt mountain incurred in 2007 when buying big in America. What all that will do to First’s large investment plans, some of it heading ADL’s way, is unclear.

One thing is clear. Economic history teaches us, time and time again, that the interplay of state economic power and commercial ambition can never be reduced to simplistic mechanical models. Pull a lever here. Measure the resultant growth spurt there. It never quite works like that. ADL builds beautiful buses. May it sell many more of them. But building successful economies is about more than trying to undercut your neighbour’s corporate tax rate by a few percentage points.