Alexander McCall Smith: Faith, not reason, is behind this political crisis

Ben Schott – he of Schott’s Original Miscellany fame – published in 2013 an extremely useful guide to German compound nouns.

The contrived words in the pages of Schottenfreude are described as “German words for the human condition” and include such gems as Hochkommakrankheit – a banal obsession with (or general confusion about) the deployment of apostrophes – Gaststättenneueröffnungsuntergangsgewissheit – defined by Schott as total confidence that a newly opened restaurant is doomed to fail – and Mahlneid – the feeling of envy one experiences in a restaurant when one sees the orders being taken to the neighbouring table. Mahlneid is real, even if the word is made up. Who amongst us has not felt that one’s own choice, yet to be delivered, will be far less appetising than the dish one sees the waiter serving to another? Such envy is, I think, every bit as much a part of the human condition as Bluthochmut – the pride some people take in having a rare blood type or Flughafenbegrüssungsfreude – that childish delight we all experience on being greeted at an airport.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFanciful though many of Schott’s compound nouns might be, there are some that spring from real insights into feelings that many of us will recognise. Coming across these in Ben Schott’s list, one thinks: yes, precisely; that is exactly how I feel; that is precisely how it is. And one then feels a certain envy for the German language’s ability to express so accurately feelings for which we simply have no English term. And then one begins to think about the issues to which these words give rise, and what these words say about our world.

A particularly interesting example is Zeitungsdünkel. Schott translates this as “newspaper arrogance” or, specifically, the feeling of consternation that flows when you find out that people read a newspaper of which you disapprove. This is a very common feeling, experienced by many readers of quality papers who discover that somebody with whom they have dealings reads a newspaper that is distinctly lower on the intellectual pecking order. This consternation may be tinged with regret that people read what they read, when they would – in your opinion – be far better informed and indeed far happier if they were to read what you yourself read. Take The Sun as an example. Now The Sun is a paper that has its part to play, and it is distinctly better than was The Daily Sport, which stopped appearing in 2011. But when you see a van parked in the street it is not unusual to see a copy of The Sun prominently displayed on the dashboard. You might also see The Daily Record so displayed, although that paper does not usually evoke as strong a visceral reaction as does The Sun. And you think: how much better it would be if the men (and they will be men) reading that paper could spread their wings a bit and read The Scotsman, the I, or The Guardian. But that will not happen, because people are loyal to their newspapers and rarely change. They may also think – falsely – that these latter newspapers will have little to say to them.

But it’s not just regret as to the level and focus of reporting that may be at play here – there is also personal conviction. People have strong views about their newspapers and not untypically will refuse to read anything other than the paper that embodies their existing views. This is a noticeable feature of readers of The Daily Telegraph and The Guardian. It is not impossible that there will be people who read both these papers, but I suspect they are few in number. Telgraphisti want their views confirmed just as much as do Guardianistas. Both newspapers contain interesting and useful journalism, but both are catechisms for a particular Weltanschauung. I know one who reads The Guardian religiously and who actually shudders at the sight of somebody reading The Daily Telegraph. That, if course, is a manifestation of Zeitungsdünkel. There will, I am sure, be examples of Daily Telegraph readers who experience similar revulsion for The Guardian of for The National, or of Spectator readers who do not like to see The New Statesman being read opposite them on a train.

The reason why people will not read a selection of newspapers is probably to do with our desire to have our views confirmed rather than challenged. And this takes one into very interesting psychological territory, recently explored by the public opinion specialist, Bobby Duffy, in his remarkable book, The Perils of Perception. Duffy’s book should be required reading for those who want to understand how it is that we have got ourselves into our current political crisis. His essential thesis is quite simple: most of us are wrong about nearly everything that we say we believe. He tests this proposition against a wide variety of popular and strongly held beliefs, and discovers that the facts upon which we base our views are often simply not true. And yet even when confronted with the manifest falseness of their assumptions, people are very unwilling to reassess the situation and come to a different conclusion. That’s because we believe what we want to believe – and what we want to believe may not be supported by the evidence. If this sounds familiar, in the light of recent political debates – and outcomes – it is because a large proportion of the population, on both sides of the major political debates, has no interest in listening to views that differ to their own. Their convictions are a matter of faith, and faith does not rely on facts and rational argument. Faith is something quite different.

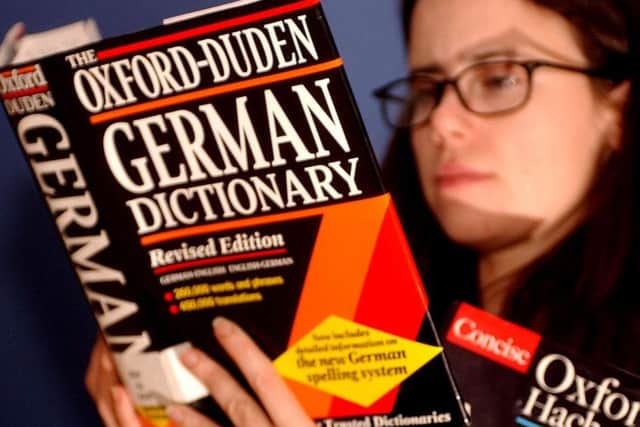

There is probably a German compound noun to express that proposition, but I have not found it yet. Those with good German dictionaries might care to compose it. It will, I think, be a somewhat melancholy-sounding word, and will also be more than usually long.