Alex Massie: 2014, Scotland’s year for thinking big

‘Scotland small?” asked Hugh MacDiarmid. “Our multiform, our infinite Scotland small? Only as a patch of hillside may be a cliché corner/To a fool who cries ‘Nothing but heather’…” Perhaps so. The national fondness for self-analysis – even, an exasperated English critic might suggest, for self-absorbed navel-gazing – can be indulged to excess. A richer seam than Lanarkshire coal and one which is far from exhausted.

The passing of the old year and the arrival of a new edition is, naturally, another moment for considering The Condition of Scotland. 2014, for reasons obvious to even inattentive citizens, is an especially propitious occasion for pondering where we have been and where, as a people, we may yet go.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt will, after all, be the Year of Scotland. Perennial highlights such as the Edinburgh Festival will be buttressed by the Ryder Cup and the Commonwealth Games and we will frequently be reminded of the cliché that “the eyes of the world” will be upon us.

For once, however, that hoary old piece of self-aggrandisement has some merit. 2014 will be a year in which Scotland’s future becomes a matter of interest to people far beyond this small country’s borders. The Ryder Cup and the Commonwealth Games will entertain; both will be well-staged. Except in the provision of new sporting facilities, neither will have a lasting impact. They are parties to be enjoyed, they will not change who we are or how we see ourselves. Anyone trying to persuade you these games might have that kind of an impact is peddling snake oil. This includes government ministers.

The Commonwealth Games will doubtless inspire many fevered comparisons with the Olympic Games. These are reasonable in the same sense as the Scottish Cup final is akin to the Champions League final. They are each games of football but the resemblance ends there. I doubt Scottish success in Glasgow will “inspire” a nation, far less have a material impact upon weightier matters of true, which is to say, of lasting, importance.

These sporting dramas are fripperies. The real action lies elsewhere. The 700th anniversary of Bannockburn in June and the independence referendum in September are the twin poles supporting these discussions of Scotland’s past, present and future.

The symbolism is arresting: on the 700th anniversary of the battle that secured Scottish independence, the country may vote to rise and be, as the Corries put it, the nation again that sent proud Edward’s army home to think again. It is a nice conceit but, in the end, little more than an accident of timing.

The idea that Scots previously reluctant to support independence will be persuaded to do so by some flag-waving and tub-thumping in a Stirlingshire field is, in the end, an idea that insults the average Scot’s ability to reason. Moreover, Bannockburn – and the memory of it – belongs to no particular party. It is a victory for unionists to celebrate just as keenly as one nationalists reasonably cherish.

For without Bruce’s victory at Bannockburn it is possible, even probable, there would have been no Act of Union. Scotland would have been incorporated within England. In time Scotland, and the idea of Scotland, would have withered. In law, education, religion and much else Scotland would (probably) have become a lesser and certainly less distinctive place. Bannockburn made eventual union, as distinct to incorporation, possible.

Indeed, there is a non-trivial sense in which Scotland’s greatest achievement since 1707 has been to survive as a distinct place at all. It was the Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau who remarked that living next to the United States was “in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly or temperate the beast, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.” As with Canada, so with Scotland’s relationship with our own, much larger, southern neighbour. So that survival – the careful husbandry of a distinct Scottish identity and perspective – is not to be treated lightly. History is only occasionally inevitable and Scotland’s survival was never one such certainty. The map of Europe is littered with buried memories of countries that have ceased to be.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat we still have a Scotland over which to obsess is, then, something today’s nationalists owe to their Unionist opponents’ ancestors. Scotland was never so surely British – that is, the idea of independence was not even a fringe enthusiasm – as in a Victorian era that simultaneously revived and celebrated the cults of Wallace and Bruce. We might, that is to say, be proudly British but we’d insist on being Scottish too. Modern Scottish nationalism would not be possible without what we might term a kind of nationalist unionism.

The former need not contradict the latter. Indeed for at least some Scots, Britishness allowed for the most magnificent expression of Scottish genius. It allowed Scotland to play to a bigger audience in a higher league. The auld sang had been put away for good, but the new tunes were, if different, just as fine.

Perhaps that no longer applies. Perhaps, as Alex Salmond and other nationalists avow, Britishness is no longer “fit for purpose”. Though if this is the case it seems strange the SNP’s vision of life after independence is so comparatively timid and so keen to maintain so much of what might be deemed Britain’s cultural and political architecture. Politics and culture cannot be easily separated.

The SNP’s argument that politics can be cleaved from culture at no cost or without changing the “social Union” with the rest of the United Kingdom is cute but, in the end, fanciful. Rejecting the idea of Britain as a political entity must, in ways we cannot altogether foresee, change the idea of Britain as a cultural entity. A measure of estrangement must follow and the ties binding the peoples of this island together must become looser.

That may be what the people of Scotland desire (though they have not yet told opinion pollsters it is). A rigorous cost-benefit analysis may point to a future as an independent state but, as with the Union itself, gains in one area will be (at least partially) offset by losses in another. There is nothing reprehensible about that. But it is dishonest to suppose or insist that independence comes at no price whatsoever. By all means work, as Alasdair Gray once suggested, “as though you live in the early days of a better nation” but accept that those early days might be difficult or awkward ones.

In fact, Salmond’s great achievement has been to bring his party – and by extension his country – to a moment in which the previously unthinkable becomes entirely thinkable. By definition, merely holding a referendum makes independence possible in a way it never previously was. That, quite properly, is something of which he can be proud.

2014, then, is a year in which for once some measure of hyperbole seems appropriate. It is a year that might yet change everything. Even a No vote will not be without consequence. The Union, and our sense of ourselves, will change this year even if Scotland votes No. Scotland forever? For sure, but what kind of Scotland? That, you might say, is the rub.

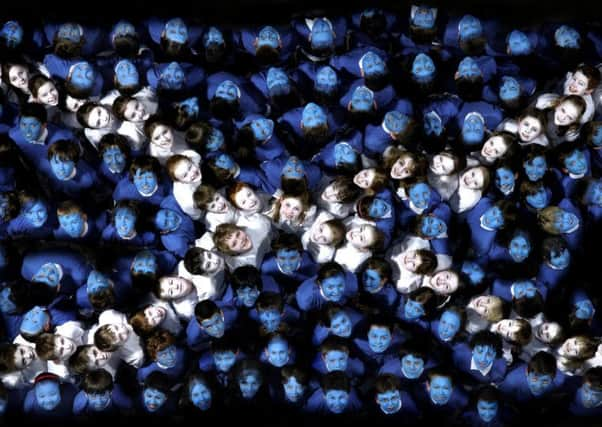

So this is a year in which Scots should hold up their heads, lift their eyes to the horizon and be reminded they come from nothing small.