Alan Steel: News of markets' death is greatly exaggerated

I started in the industry in January 1973. In October that year the FTSE Index fell, and over the next 15 months it was down 74 per cent. Pure coincidence. Nothing to do with me.

The markets crashed again on 19 October, 1987, which became known as Black Monday. Back in 1929 it was in October that the Wall Street Crash began, triggering the Great Depression of the 1930s. It gets worse. In October 1917 a stockmarket index actually fell to zero. In Russia. Something to do with a revolution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

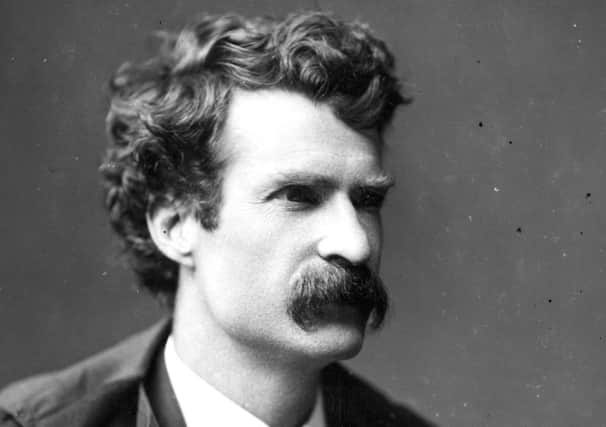

Hide AdTo be fair, Twain hedged his bets by pointing out that September also wasn’t a great month to invest. He then added all the other ten months just to be on the safe side, marking his card as probable pessimist.

There’s now a consensus yet again that the world is a dangerous place for investors and that stagnation is the best we can hope for. Interest rates are close to zero and worse. I read recently that more than $13 trillion of private investor money sits in negative yielding bonds. That’s where you pay governments for the privilege of using your savings. Daft or what?

It’s the start of the financial crisis in September 2008, rather than October, that’s still blamed for all this fear over stock markets.

But now it’s probably our “recency bias” as investors, plus constant doom-mongering that won’t let us forget it, despite the positive performance of most equity investments since then.

Patience and perseverance can ride through these shocks and falls. I’ve seen it personally over the past 43 years and history tells us that the same goes for the period after 1929 too. Share prices and indices can go down sharply as well as up slowly, as we keep being reminded.

But shares also pay income, known as dividends. And over time they’re powerful protectors of wealth.

Let’s consider the last ten and 20 years. The FTSE All Share Index is up just 24.4 per cent over the past ten years. But when reinvested dividends are added, it’s up over 77 per cent. Over 20 years the index is up almost 94 per cent, rising to 270 per cent when reinvested dividends are factored in (according to figures from Lipper). Some difference.

Investors are clocking on to the idea of buying funds that cheaply track the index and reinvested dividends. Actively managed funds aren’t worth the extra cost, or so it goes. Tell that to long-term followers of Neil Woodford, who until relatively recently was at the helm of the Invesco Perpetual High Income fund. Net of all charges and with net dividends reinvested it’s up by more than 103 per cent over ten years and by 697 per cent over 20.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat’s possibly more interesting is that going back to 1995, a period including both the dotcom bust and the financial crisis and during which we experienced two 50 per cent falls in the FTSE All Share Index, dividend payouts from Woodford’s fund fell by much less. Indeed, dividends in the fund rose following the 2008 crisis.

These days I would be more inclined to make use of global income funds that take advantage of faster growing economies. Look at James Harries’ record at Newton over the past ten years. He launches a new Global Income fund next month at Troy. It may pay dividends to join him on his new journey.