Aidan Smith: Jimmy Savile too big a demon for Top of the Pops to overcome

“Is that a boy or a girl? What’s he/she singing about? What a horrible racket. Do you really like this stuff?” To which the only reasonable reply was: “Sorry, Dad, but I do. I’ve listened to your Mantovani and your Semprini long enough. I’ve heard the last I want to hear of James Last. I’m really fed up of Kenneth McKellar singing “Oh these are my mountains” like he’s just turned a corner and found them – if they were that special how come he keeps forgetting where they are? No, this is MY music.”

Yes, Top of the Pops was a fantastic show. The means by which oldsters could hang on to the last tie-dyed tassels of their youth. Then, when their youth had finally given up the ghost, the means by which they could rant at modern ills. It was the means by which parents and their children could commune, for a while at least. And best of all, the means by which adolescents could begin to form identity and personality before declaring: “It’s our world now.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWas pop music in the 1960s, the 70s and for part of the 80s really that important? Hard to believe now, but it was. Was Top of the Pops that important? Yes, which might explain why the BBC is thinking about bringing the show back. But music has changed. It lacks the identity and personality it helped give those kids, with the faceless acts of the turn-of-the-century being replaced by things even worse: bedwetter pop, privately-educated pop, poshos dressed as farm labourers. And then there’s the Jimmy Savile factor. Who’s nostalgic for that?

Certain Tops of the Pops performances are burned in the memory of those who witnessed them. Arthur Brown’s rendition of Fire in a flaming head-dress is burned on the old hippy’s scalp. Where were you when Rod Stewart played keepy-uppy with a football during Maggie May, when David Bowie puckered up to his guitarist Mick Ronson during Starman? Watching straight after a Fray Bentos tea, of course.

My own father stayed “with it” longer than any of my friends’ dads – which brought its own embarrassments – but he too was challenged by Top of the Pops. One Thursday in 1972 he wanted to know what I like about Roxy Music’s Pyjamarama. I was too embarrassed to say it was the corny theatre of the band strumming the opening chords with their backs to the cameras, then leaping round in unison. Dad said the lyrics were “trite” but I was too thick to know what the word meant. Tragically I didn’t find out until later that the entire song was composed from First World War love letters, which surely would have won me the argument.

But I cannot think about Top of the Pops now without being reminded of Savile. He haunts the show in memory like he used to stalk its dark recesses when it was a 15 million ratings smasheroo, looking for “young crumpet”. I’m not sure that even a name-change – the revival would probably get one – will completely expunge the image of the cigar-chomping peroxide monster, dripping with jewellery and lust.

Savile presented the very first Top of the Pops on 1 January, 1964 when the BBC, still nervous about this thing called pop, trialled the show in a converted Manchester church, far away from the sparkling new Television Centre. Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones recalled a huge amount of chaos, everyone seeming to make it up as they went along, but Savile “kept everything together”.

If youngsters watching approved, their elders definitely didn’t, as Dan Davies recalls in his excellent book In Plain Sight: the Life and Lies of Jimmy Savile, with much of the dissent reserved for the host. The letter of complaint from a retired naval officer went: “Really horrific. It ought to have an X certificate. And there was Mr Savile presiding over the orgy like a Puritan clergyman resurrected from his own churchyard.”

Reading that at the time, the kids must have loved Top of the Pops even more. A programme for us and daddy-o hates it! But Savile, as we know now, did a whole lot more than just “preside”. In the revelations of how he preyed on teenage girls, the programme was central to them.

Davies quotes one of the investigators as saying: “When [one of the Top of the Pops victims] talked about the force that he used, the power that he used, the violence that he used, the coercion that he used, that was the point when I concluded: ‘This is a really nasty offender, and this guy has offended against an awful lot of people’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA 1972 report to a BBC inquiry following the suicide of a 15-year-old girl who had been on the show - suppressed for 40 years but eventually published under Freedom of Information - acknowledged the problems of the Top of the Pops format: “ … It introduces into the labyrinthine TV Centre a substantial number of teenage girls … ”

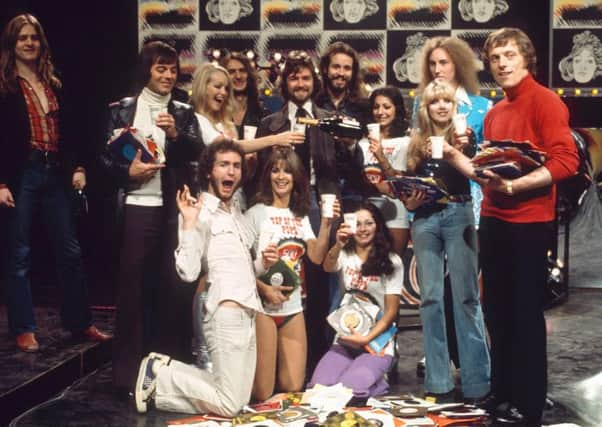

When the Savile revelations broke, the Beeb were careful he didn’t turn up in any nostalgic re-runs, but these did continue, and you couldn’t help but feel uneasy when one of the other presenters draped his arms round shop-girls from Grimsby who’d waited a year to be among the audience - or when Dave Lee Travis chased Legs & Co across the underlit dancefloor in a Benny Hill-style jape.

The show was part of everyone’s growing up, which the hideous Savile exploited to accelerate the development of a few. He hasn’t killed pop music but he’s done for Top of the Pops.