Obituary: '˜Zander' Wedderburn, international authority on the psychology of shift work

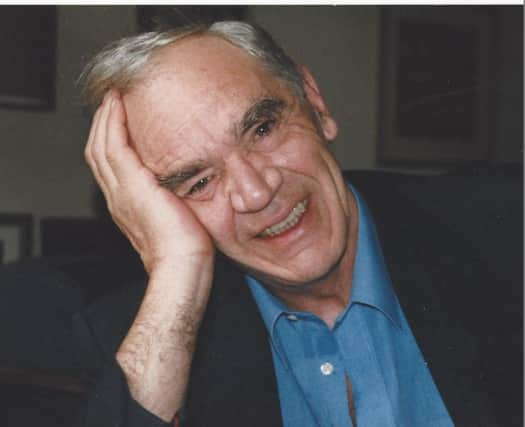

Zander Wedderburn was a man whose mischievous sense of humour may have belied his achievements as a respected professor; younger players caught out by him on the squash court – less by his skills than by his skillful methods of distraction – may not have been aware that their pipe-smoking, septuagenarian opponent was an international authority on the psychology of shift work.

Whatever the circumstances of their meeting, those who spent time in his company will find it hard to forget him. He is remembered as a big-hearted, optimistic and entertaining character, a devoted husband and father, a wise mentor and, in retirement, a man who truly believed that life was for the living.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlexander Wedderburn, known to all as Zander, was born in Buckingham Terrace, Edinburgh in 1935, to AA Innes Wedderburn, a solicitor and auditor to the Court of Session, and his wife Innes nee Jeans. His father was also a partner with Alexander Morrison in Queen Street and captain of the Royal Burgess Golf Club in Barnton, and his mother had graduated from the University of St Andrews but devoted her life to raising their four children.

Young Zander was evacuated, along with his family, to Boat of Garten in the Highlands for a year at the start of the Second World War, and later attended the Edinburgh Academy. He was Dux of the school but always maintained that his contemporary, Willie Prosser – later the Rt Hon Lord Prosser QC, Court of Session Judge – would have been more deserving of the title.

He did his National Service in the Navy, where he learned to type and to play the guitar, and then he took up his scholarship to Oxford, studying classics at Exeter College. He enjoyed the social aspects of university life, including playing folk music and singing with a very deep voice at the Heritage Club, but decided to switch to a subject for which he felt more of an affinity. Making the move to study psychology, physiology and philosophy, focusing on psychology and philosophy, turned out to be a canny move.

At Oxford he took part in the famous sleep experiments conducted by Professor Ian Oswald, which sparked his later interest in shift work and its effects on the brain. He graduated in 1959, with the rare distinction of having his Honours project – a much-cited joint paper with Jeffrey Gray challenging Donald Broadbent’s theory of binaural attention and switching between ears – published.

He married his childhood sweetheart, midwife Bridget Johnstone – for whom he would later create an extraordinarily moving tribute – and they moved to Corby in Northamptonshire, where he was a foreman for Stewarts & Lloyds, which would later become part of British Steel Corporation. While there he was awarded a research fellowship which enabled him to develop his expertise in the effects on workers of shift patterns.

He then worked in industrial relations at the University College in Cardiff, and in 1968 moved back to Edinburgh to get his PhD from Heriot-Watt University, where he would become a Professor of Psychology in the School of Management – including a spell as head of school – until 2000.

As someone who was particularly interested in the interface between research and practice, he had a ten-year stint as editor of the Bulletin of European Shiftwork Topics, and was founding editor of the Shiftwork International Newsletter. He was also president of the British Psychological Society in 2013/4 – only the third occupational psychologist to have held that position in the past 50 years.

Despite the weight of his academic responsibilities at Heriot-Watt, he was generous with his time and talents when it came to helping students, colleagues, alumni and others. He contributed to university governance, community, social and political causes, and was known for being excellent company – a true individual. He was passionate about politics, standing as a Labour councillor in his twenties, then leaving the Labour Party temporarily to stand as a Social Democratic Party candidate in local and national elections in the 1980s; he narrowly failed to get elected.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdZander and Bridget spent much of their life together in Charlestown, Fife, moving to the West End of Edinburgh in the mid-1980s. They both had a strong faith, and were regulars at the Church of St Andrews and St George’s West. Zander did not regard retirement as a time to slow down: as a member of the Broomhall Curling Club he regularly took part in curling competitions (latterly continuing to play online when the physical game became too much for him), and was a popular personality at the Dean Tennis and Squash Club.

As a septuagenarian who was still deeply attached to his pipe, he competed in over-70s squash competitions, including a four-nations tournament run by Scottish Squash. After taking part in one over-75s competition, he proudly told friends that he was the runner-up, before mentioning that there had only been one other player involved.

As a founding member, he maintained a keen interest in the Lennox Street Residents’ Association until the end of his life, regularly attending local community organised events.

One of his retirement projects involved the setting up of a small publishing company, Fledgling Press, and it was through this venture that he published the profoundly moving B: A Life of Love for his wife. Some 50 years after they were married, his sweetheart was disabled by Alzheimer’s, and Zander wrote an extended love story that he could read to her to remind her of the many special years they had shared.

The book describes how she first caught his eye while she was a pupil at St George’s School for Girls and he was at Edinburgh Academy, and tells how he awkwardly proposed to her while punting on a river in Cambridge, and how she declined to kiss him until her father had given them permission to marry, which they obtained by calling him from a phone box. It goes on to describe the moment on the night before their wedding when they climbed Arthur’s Seat together, and how much he loved her free spirit over the subsequent years, including her proclivity for doing the gardening in her bare feet and occasionally – in their entirely secluded property - with her bikini top off when it was sunny.

Bridget spent her final years in a nursing home, her husband visiting her almost every day whenever he could, and she died in January 2016. Zander had been suffering from oesophageal cancer and died peacefully at home in February while listening to Woody Guthrie with two of his children. After his passing, his children found a quote by Zander in a handwritten notebook which they feel sums up his attitude to life: “What I really value is people who are authentically themselves and genuine, who also manage to live a useful life showing respect and concern for others”.

Zander Wedderburn is survived by his children Chris, Pete, Joanna and Rebecca, by eight grandchildren, by his sisters Kirstie and Sue, and his younger brother John.

ASHLEY DAVIES