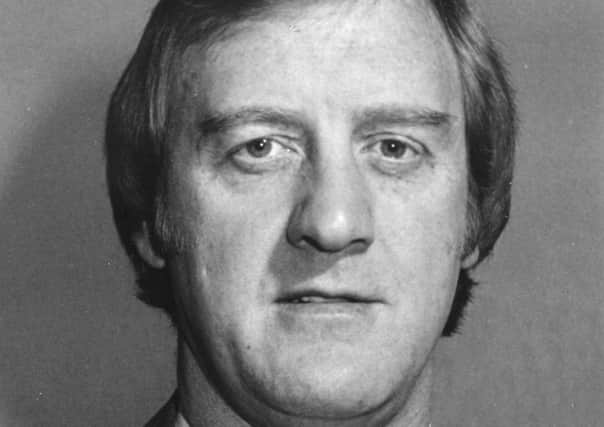

Obituary: Robert MacPherson, tireless worker for tenants' rights, despite being severely disabled

To many of his friends and family, Robert MacPherson may still be remembered firstly as a charismatic publican, but 20 years ago multiple sclerosis saw his life change in ways he could never have imagined. Instead of curbing his intentions however, the diagnosis merely set him on a different path

In the face of his greatest challenge he became an irrepressible campaigner and authoritative voice on inequality and injustice, on issues affecting tenants and the disabled, and worked for the greater good of Edinburgh. Throughout he maintained a common touch, dignity and sense of humour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven when the condition deprived him of the use of all his limbs, he continued to volunteer on the board of two organisations and to champion disability rights.

It was cathartic, he said: “It’s good for the soul – I feel I’m contributing, it keeps the head active! “

Born at Edinburgh’s Simpson Memorial Maternity Pavilion, he grew up in Craigmillar and the Inch, attending Liberton High School where he captained the rugby team. A sporty youngster, he also played badminton and football, winning an under-18s trial for Scotland.

His father, William, worked for the Post Office, in charge of the messenger boys, and on leaving school his son followed him there, delivering telegrams on a pushbike and building an encyclopaedic knowledge of the capital’s streets.

In his 20s, MacPherson began working in the pub trade before becoming a sales rep, through which he met his wife Susan, with whom he had two children.

By the late 1970s however, he was firmly set in the licensed trade, managing the Beau Brummel in Hanover Street, then Champagne Charlie’s in North Castle Street, before opening his own establishments – Blythe Spirit and La Coquette, both in Rose Street. As a successful publican he forged many enduring friendships and proudly served as captain of the Edinburgh Licensed Trade Association Golf Club.

His diagnosis of multiple sclerosis came at the age of 48. By that time he and his wife had split. He was with a new partner, Rosaleen, and was running Dunedin private hire car firm. He then joined Scottish Golf and Travel and enjoyed guiding golfers on tours of Scotland and Ireland.

But as his health deteriorated he was forced to retire, wheelchair bound at 52. Undeterred, when he acquired a Lorne Housing Association flat, he attended the AGM and volunteered to sit on its board, a post he held for the longest possible term of 15 years, continuing in his position through its incorporation within Port of Leith Housing Association.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmong his contributions to the association were his talks to local authority staff highlighting the service user’s point of view. More recently he was a board member of the association’s social enterprise, Quay Community Improvements. His work won him a national Unsung Hero award for his commitment to better housing and representing tenants.

“This was an extremely fitting accolade for someone who was always on the lookout for innovative ways to improve the quality of life for everyone in Leith,” said the association’s chief executive Keith Anderson.

“Robert was a selfless campaigner against inequality and injustice, and a remarkably courageous man.”

He was also a champion and board member of the Lothian Centre for Inclusive Living, gave monthly talks to City of Edinburgh social carers as part of their training, and for many years gave an annual talk to second year occupational therapy students at Queen Margaret University.

Another of his causes was the campaign to save beds at NHS Lothian’s specialist Lanfine neurology unit at the Astley Ainsley Hospital, where he had benefited from regular specialist care. Despite his efforts and those of fellow campaigners, the unit was reduced to just four beds for assessment and neurorehabilitation, removing the respite service he had valued.

His grit and determination belied the presumption he once made that he would take a pill if he ever got to the stage of not being able to feed himself. In an interview with MS Connect magazine he explained: “When that day arrives, your lust for life is a hell of a lot stronger than that. You may not like it, you certainly do not like it, but I can assure you there’s more to life than having to put up with that. I don’t like it, I hate it, but I’m not ready for ending things and I never will be.”

He tackled the change in circumstances head on and was fond of visiting some of the city’s top restaurants, the Michelin-starred The Kitchin being a particular favourite. He also embraced technology, using a voice-activated computer plus an environmental control system to maintain some independence. The latter allowed him to operate the television, telephone, doors and lights with a few taps of his head and was connected to the chin control he used to operate his wheelchair.

As recently as 2016, he wrote of his own personal challenges and in particular the difficulties following changes in legislation around the funding of overnight care.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Having the right support allows me to live a life – get out and about, meet my friends, volunteer. I’ve got a purpose: I’m contributing to the life of my friends, family and community, and that gives me a feeling of self-worth.”

He is survived by his children Callum and Gemma, sister Bettany, and three granddaughters.

ALISON SHAW