Obituary: Dr Adam Matthew Neville, university principal, civil engineer and world authority on concrete

Packed into a prison cell so small the inmates slept in a row on their sides, Adam Neville could never have envisaged that the unforgiving concrete of the floor that formed his bed would one day be the substance to propel him to international acclaim.

Aged just 16 and incarcerated by invading Russians as he tried to flee his native Poland, he had no idea then what the ensuing hours or days would bring, far less if there was any future ahead.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the teenager, so bright he had won a scholarship trip to England, life was to become brutal: sentenced to hard labour in an Arctic gulag, he survived near starvation, a 4,000-mile journey to Persia and action with the Polish Forces at Monte Cassino.

Decorated several times for valour, in the hard-won freedom of peacetime he continued to excel, displaying the determination and zest that sustained him in war and which drove him to many new adventures, opportunities and renown as a globally recognised civil engineer and world authority on concrete.

He was born Adam Maciej Lisocki in Krakow, where his mother Louise was a pharmacist and his father, who died when his son was 12, was a lawyer. A clever child, who started school a year earlier than his peers, by the age of 15 he had won a British Council scholarship for an essay written in English. The prize was a trip to England where he decided to stay on to attend school for a year as he was still too young to go to university.

But by this time it was 1939 and with the war clouds gathering he chose to return home to be with his widowed mother. That August Poland was divided, under the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression agreement, the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, into German west and Soviet east territories. As the Germans advanced from the east, mother and son tried to escape to Romania where Polish Forces were being evacuated to France. However the guide, who had been paid to take their small group over the border, betrayed them to the Russians. Mother and son were arrested and separated.

Adam was held in the squalid cell, he and his fellow flea and lice-infested prisoners sleeping squeezed sardine-like on the bare floor, all facing one direction. He later said that was possibly when he developed his love of concrete and his ability to sleep anywhere.

Condemned to a labour camp for being bourgeois and trying to leave the Soviet Union, he was put on a cattle truck to the Arctic and forced to walk the last leg through snow. Those who survived spent 18 months as lumberjacks, working without gloves or boots. Many perished in the freezing conditions and he recalled that, as they were dying, some of the older men gave the younger ones their food so that they might live.

After Germany broke the pact in June 1941, an amnesty gave all Polish citizens in the Soviet Union the chance to leave. Young Adam made his way across Russia and worked for a time in a factory in Uzbekistan. When he heard Polish army units were being established on the borders of Iran and Afghanistan he set off to join them. He arrived in Pahlavi, Iran, by cargo ship, sick and starving but joined the Free Polish Forces led by General Wladyslaw Anders.

Almost unbelievably, he was reunited with his mother who had also made the horrendous journey alone, joined the Forces and was serving as a field hospital pharmacist. Her son went on to serve in Iran, Iraq and Palestine, where he finally matriculated, and in 1944 fought with the 2nd Polish Corps in Operation Diadem at Monte Cassino, Italy. He was decorated for gallantry four times and awarded the Cross of Monte Cassino and the Polish Cross of Valour for exceptional courage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

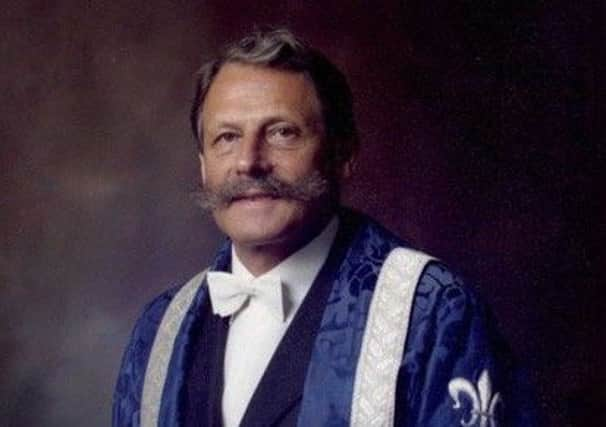

Hide AdDemobbed with the rank of captain, he resumed his studies and began to cultivate the handlebar moustache he sported for the rest of his life. After graduating from the University of London with the best first class honours engineering degree his professor had seen awarded, he did his master’s and went on to lecture at Southampton University.

He then headed to New Zealand, working as an engineer and then lecturer at Christchurch University. And it was there that he discovered the name Neville – after visiting a former soldier, Ted Wright, he had fought alongside in Italy. He was introduced to Ted’s niece Mary, with whom he promptly fell in love and they married after a whirlwind romance. Seeking an alternative to his Polish surname that was short, easy to spell and meaningful, they decided on Ted’s suggestion of an old family name, Neville.

The couple had two children in New Zealand but the family came to Manchester in 1955 where their father lectured, completed his PhD and served in the Territorial Army as a Royal Engineer, being promoted to major.

A globetrotting life followed – initially to Nigeria where Neville was the first Dean of Engineering at the Nigerian College of Technology in Zaria, then to Saskatoon in Canada and later to the University of Calgary as its founding Dean of Engineering. In the Rockies he could again indulge his love of skiing, nurtured as a boy in the Tatras mountains, and he joined the ski patrol.

Returning to the UK in 1968, as professor and head of Leeds University’s civil engineering department, he championed women as engineers, having at one time more female civil engineering students at Leeds than the total in all the rest of the UK’s universities.

A decade later he was in Scotland as Principal and Vice-Chancellor of Dundee University, guiding it through challenging times, facing financial difficulties and pressure to merge with other institutions. He advocated focusing on research excellence, laying the groundwork for its School of Life Sciences to emerge as a world leader. He was presented with an honorary degree in 1998 and a prestigious annual lecture is named after him.

He left academia in 1987 to become an engineering consultant, giving evidence in major cases around the world. He specialised in concrete construction and pioneered the study of high alumina in cement, controversially predicting its unstable nature in 1963, the same year his Properties of Concrete book was published. Known as the ‘concrete bible’, it has sold more than a million copies and been translated into 13 languages.

Despite high office, he continued to research throughout his career, produced 11 books, more than 250 papers and was honoured with doctorates, awards, medals and fellowships from institutions and countries around the world. In 1994 he was made a CBE.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn inveterate traveller, invariably with only hand luggage to save time, he spoke seven languages and had visited more than 250 islands and countries, including all of Africa and the Americas.

Latterly he and Mary lived in London. His health suffered from the cold and starvation of his youth and his hearing had been impaired by shelling, but he remained indefatigable, skiing until he was 80, travelling for as long as he could and socialising until the end.

He is survived by Mary, their two children Elizabeth and Andrew and five grand- children.

ALISON SHAW