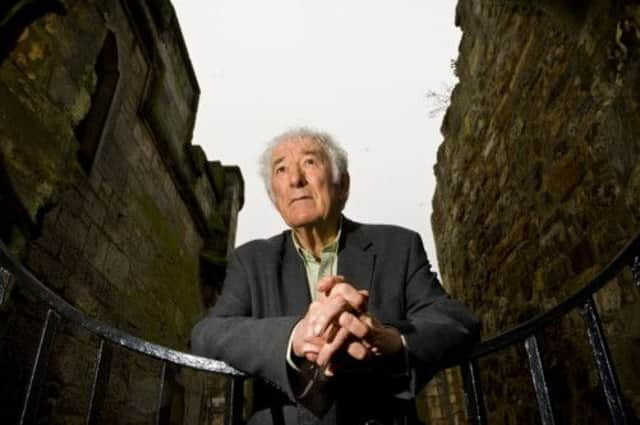

Obituary: Seamus Heaney, poet

Nobel Laureate and elder statesman of poetry, Seamus Heaney was described by Robert Lowell as “the most important Irish poet since Yeats”. Also acclaimed as an essayist, translator, playwright and lecturer, he combined passion and authority with a great modesty.

He was, said Blake Morrison, “that rare thing, a poet rated highly by critics and academics yet popular with ‘the common reader’”. His books (in poetry terms, at least) have achieved extraordinary sales: according to one estimate, he accounts for two-thirds of the book sales of all living poets in the UK. In the course of a career lasting almost 50 years, he was garlanded with almost every award in the poetry canon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHeaney was born in 1939 in the three-roomed thatched farmhouse at Mossbawn, between Castledawson and Toomebridge, the eldest of nine children. Later, his family moved to nearby Bellaghy and he won a scholarship to St Columb’s, a Catholic boarding school in Derry.

He began to write poetry while studying English Language and Literature at Queens University in Belfast, where he graduated with a first class honours degree in 1961.

While training to be a teacher, he undertook a placement under headmaster (and writer) Michael McLaverty, who became his mentor and encouraged him to publish. Soon afterwards, he joined the now legendary writers group run by Philip Hobsbaum at Queens, which also included Derek Mahon and Michael Longley. Creative sparks flew; they spurred each other on.

Three poems published in the Christmas edition of the New Statesman in 1964 caught the eye of an editor at Faber, who published Heaney’s first collection of poems, Death of a Naturalist, in 1966. It drew heavily on his upbringing, matching the rhythms and landscapes of rural Ireland to a verbal inventiveness akin to Ted Hughes and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Prizes and accolades started to flow.

Heaney returned to Queens as a lecturer for a time, but moved with his wife, Marie Devlin, and their young family to the Republic of Ireland in 1972, taking a job teaching English in Carysfort College in Dublin.

He seemed relieved to be away from the tensions of the North. When he was included in an anthology of British poets in 1982, he responded (in poetry): “My passport’s green/ No glass of ours was ever raised/ to toast the Queen.”

He did not flinch from addressing the Irish political situation in his poetry, but resisted any pressure to bestow meaning where there was none or, far worse, become a spokesman. In his collections Wintering Out (1973) and North (1975), he wrestled with his own frustration. “One side’s as bad as the other, never worse,” he writes in Whatever You Say, Say Nothing.

In the 1980s, there were visiting professorships at Harvard and Oxford. Heaney was an electrifying speaker, and also an outstanding critic. His engagement with other writers, particularly poets from Eastern Europe such as Nobel prizewinner Czeslaw Milosz, was crucial, both for these writers and for his own creative development.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMilosz became a friend, as many writers did. He also felt a great “fraternity” with the Scottish lyric poets of the previous generation. A photograph taken in 1990, when he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling University, shows him shoulder to shoulder with Norman MacCaig, Iain Crichton Smith and Sorley Maclean.

In 1996, Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past”.

In his Nobel address in Stockholm, he spoke of Mossbawn, of a poetry rooted in the local. The man whom critic Anthony Thwaite once described, dismissively, as “the laureate of the root vegetable” had proved beyond doubt that the local was also universal.

The Nobel Laureateship brought a degree of celebrity unusual for poets, and perhaps not entirely welcome.

Invitations now came in from all over the world. In Dublin, he was “famous Seamus” (a term coined by Clive Anderson), and he tended to wear a hat to cover his distinctive shock of white hair.

But he dealt with all of this with patience and equanimity, and continued to write, producing a new translation of Beowulf which became a bestseller and won the Whitbread Prize. His ninth poetry collection, District and Circle, won the prestigious T S Eliot Prize.

Heaney was a gracious man who had time for anyone who was prepared to be serious about poetry. He accepted an invitation to the StAnza Poetry Festival in St Andrews in 2010, turning down more high profile requests from around the world because it was, he said, “a deep poetry audience, an old connection”.

He spoke of his kinship to Scottish poets in a wonderful sell-out event chaired by fellow poet, the late Dennis O’Driscoll.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTributes to Heaney praise his humility. He himself pointed out to an interviewer that the word “humble” derives from the latin word “humus”, meaning earth. One is reminded of the soil in his early, and well-loved poem Digging, or the fact that his second volume of collected poems is called Opened Ground. Heaney knew his “ground” and never forgot it. He was one of the most grounded writers in the world.

Poetry, he said, was always “a grace”. And Seamus Heaney was granted the grace of finding out, early on in life, the vocation for which he was supremely gifted, and being able to pursue it. In half a century of writing poetry, he reached the height of his powers. When recognition came, he had no need of ego, he knew who he was.

But he also lived with doubt. Accepting the David Cohen Prize for a lifetime’s excellence in writing in 2009, he recalled how his first poems had been published under the pseudonym Incertus (one who is uncertain). “It is always important to be reassured,” he said.

His last collection, Human Chain, came out in 2010, winning the Forward Prize. Judge Ruth Padel described it as “a wonderful and humane achievement”.

Heaney described it as his most personal book to date, writing in it for the first time about the stroke he suffered in 2006, the human hands who helped carry his partially paralysed body down the stairs to the waiting ambulance: an everyday miracle of kindness.

In recent years, he did fewer public engagements and interviews, but when he did, he was as passionate, clever, articulate as ever. His use of language, both in his poetry, and in his ability to speak about poetry, was masterful.

Critic Brad Leithauser said: “His is the gift of saying something extraordinary while, line by line, conveying a sense that this is something an ordinary person might actually say”.

It is true of his prose as well as his poetry. That, perhaps, is the core of his brilliance.

Seamus Heaney died in hospital in Dublin, following a short illness. He is survived by his wife, Marie, and children, Christopher, Michael and Catherine Ann.