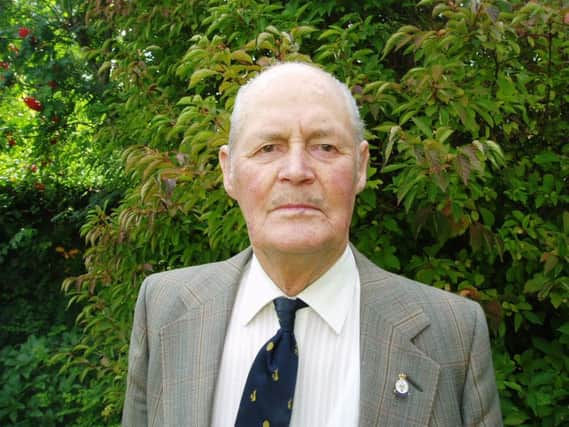

Obituary: Norman Brown, Battle of Britain Spitfire pilot

RAF Spitfire pilot Norman Brown was one of “The Few”, those who took part in the Battle of Britain in the autumn of 1940 in the skies above England and the Channel. He was never shot down, despite almost-daily dogfights against the Luftwaffe, but survived several forced landings, including flying into the metal cable of a barrage balloon floated over London to defend against low-lying enemy aircraft. Brown was believed to be the last survivor of 41 Squadron, based at RAF Hornchurch, Essex, which lost 16 pilots in action during the three-month Battle of Britain but claimed more than 100 “kills” of enemy planes.

After the war, Brown returned to the UK to gain a degree in forestry and worked for the rest of his career, until retirement in 1979, as a West of Scotland district commissioner for the UK Forestry Commission, from which a Scottish branch, Forestry Commission Scotland, has since devolved. The overall UK commission, a non-ministerial government department, is the UK’s biggest land manager, with Scotland accounting for 70 per cent of the forest land it oversees. The commission’s first chairman, in 1919, was Simon Fraser, 14th Lord Lovat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNorman McHardy Brown was born in Edinburgh on 27 July, 1919, and went to South Morningside Primary before George Heriot’s School. He volunteered for the Royal Air Force Voluntary Reserve (RAFVR) as an airman u/t pilot (under training) a few days after his 20th birthday and was called up on 1 September, 1939 as war loomed. He was posted to 3 ITW (Initial Training Wings) in Hastings, moving in April 1940 to EFTS (Elementary Flying Training School) at RAF Burnaston near Derby. He was commissioned as Pilot Officer on 7 September, 1940 – with the service number 84958 – trained in Spitfires at 7 OTU (Operational Training Unit), RAF Hawarden, Chester, and was posted to 611 Squadron at RAF Digby, Lincolnshire, immediately engaging in the Battle of Britain.

The Luftwaffe had turned its full attention to trying to obliterate the RAF’s forward fighter bases and radar stations and Britain’s survival hung in the balance. On 12 October, 1940, Brown – nicknamed Sneezy by his comrades – was transferred to 41 Squadron at Hornchurch and continued to hunt down German fighter planes.

As the RAF gained the upper hand in the Battle of Britain, Brown’s Spitfire was returning to Hornchurch on 1 November, 1940 when, in poor visibility, it overshot the RAF base and strayed into London’s Barrage Balloon defence area. He struck a cable. “The weather was still quite thick … my starboard wing struck a cable – not a pleasant discovery,” he wrote many years later in a an article for the Scottish Saltire Branch of the Aircrew Association (ACA). “My first instinct was to bale out, but I couldn’t for two reasons; I was fully occupied holding the Spitfire straight as it tried to spin round the cable and secondly I could see I was over houses. If I had tried, I would almost certainly have killed myself. As it was I struggled hard with the controls and literally ‘flew down’ the cable with the airspeed falling dramatically.

“Finally, the aircraft stalled and did what I can only describe as a violent flick roll. At this point the cable, I think, broke and tore away part of the wing, and I went into a steep dive. On trying to pull out, the Spit turned over on it’s back at about 1,000ft and I thought all was over and I momentarily experienced the most unusual sense of complete tranquillity…”

He went on to describe how he spotted a small housing development site just beyond a railway line and decided to try and land there. He aimed to hit the fence to reduce the plane’s speed, as the site was not very big and there were houses at the far end. “I don’t recall much about the impact except that it was very much more violent than a normal ‘wheels up’ forced landing, which I had previously experienced. I was very confused and found myself in almost complete darkness and realised that the Spit was upside down and there was only a little light through the windscreen as it was buried in soil through into which it had ploughed.”

He recalled the stench of petrol and thought “he was about to be barbecued”. The canopy had slammed shut but two men who had been working nearby came to his rescue. “A hob-nailed boot smashed the canopy. I was never so pleased to see a hob-nailed boot and I was pulled out after I released my straps.”

In a separate article for the Scottish Saltire branch of the ACA, Brown wrote: “The autumn of 1940, what memories! So very hectic, exhausting and frightening. The dangers, fears, excitement, the sadness and the fun, shared with some of the best people one could ever hope to meet. Waiting! Time is passed dozing, reading, listening to music or playing cards. The telephone rings: ‘41 Squadron scramble!” A dash for the dispersed Spits.

“Climbing at maximum rate, oxygen on at about 13,000ft, getting colder – probably about minus 30 degrees Centigrade … a gaggle of Messerschmitt Me109s dive on us out of the sun, their trails concealed by a drift of high cloud … gun button on to ‘fire’ … violent turns to meet the attack head on …chin pressed down on to chest and vision …darkening as G force increases … orange streaks of cannon fire pass too close … aircraft everywhere … a glimpse of an enemy fighter … a quick burst … more tight turns … a Spitfire dives past on fire and below, an Me109 with a Spitfire on its tail disintegrates … more evasive action, dive and tight turns and then level off.” Back on base, “we thankfully retire to the local hostelry for the odd pint … there is no mention of absentees. So ends another day.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHaving left the RAF in 1941, Brown returned to Scotland and forestry. As a result, he volunteered after the war to assist RAF 317 Squadron, on the ground in the western-controlled zone of Germany, in Operation Woodpecker, a reparations scheme to get badly-needed timber to the UK where wood had been rationed for civilians during the war in favour of the military effort. In 1947, the operation also provided timber and peat for heating to Germans civilians, who had survived the war only to face displacement and freezing temperatures.

Back in Scotland, Brown worked for the Forestry Commission, based alternately in Peebles, Jedburgh and Glasgow, latterly as district commissioner for the West of Scotland, which made him a regular and popular visitor to the Highlands and Islands, which he loved. After the passing of the 1968 Countryside Bill, he helped ease the transition from the commission’s initial mandate – the production of timber – to its role in conserving forests and making them available for recreational use such as hillwalking, mountain biking and horseback riding.

After retirement in 1979, Brown continued his hobbies, notably fishing and shooting – grouse, pheasant, duck or partridge – as well as golfing at Torwoodlee Golf Club in Galashiels.

Norman Brown died in the Borders General Hospital in Melrose. His wife Sheila (née Cunningham) died in 2003. He is survived by their children Ian, Peter and Elizabeth, six grandchildren and ten great grandchildren.