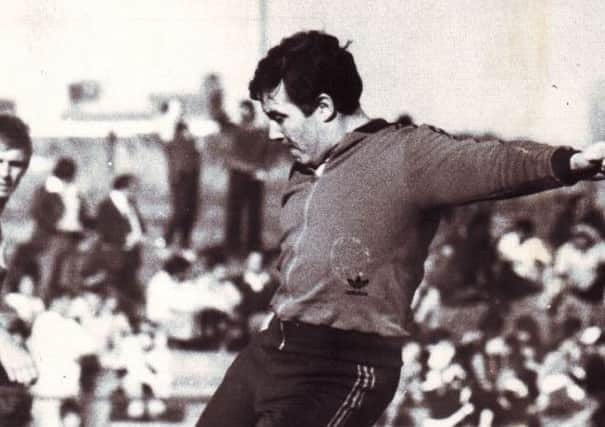

Obituary: Duncan Mackay, Scotland internationalist, Celtic captain, Melbourne player and league-winning coach

It’s a long way from Maryhill to Melbourne, but in his 82 years that’s the journey former Celtic and Scotland full-back Dunky Mackay made, prior to his death just before Christmas.

Like many before him, Duncan’s father, also Duncan, left the West Highlands for the city, where he worked at several jobs to keep a roof over the head of his family. But, this proud Argyll man insisted the young Duncan wore his Mackay tartan kilt every day – until, getting into playground scrapes when he responded to taunts of: “Kiltie, kiltie cauld-bum,” began to wear thin with the youngster, and he persuaded his parents to get him into long trousers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it was in shorts that he really made an impression at St Columba’s High School, where his exceptional skill with a football got him noticed. He moved on to St Mary’s Boys Guild – where Celtic came calling, signing him on a provisional form and farming him out to he toughened-up by juniors Maryhill Harp.

By now the teenaged Mackay had seen the great Hungarian side of Puskas and Co and the sort of attacking football he wanted to play. He had also left school and taken-up an apprenticeship as a marine engineer with David Rowan & Co, who built ships engines.

He remained a part-timer until he had completed his apprenticeship, then he turned full-time at Celtic and, during the 1958-59 League Cup campaign, he made the first of his 236 first-team appearances in a League Cup tie against Clyde, replacing John Donnelly at right back.

By the end of that season he was first choice, an Under-23 cap – he would represent that age group side four times – and, on 11 April, 1959, the 21-year-old Mackay made the first of an eventual 14 appearances for Scotland, against England at Wembley. England won 1-0, courtesy of a rare Bobby Charlton header.

Mackay’s full-back partner that day was Rangers’ Eric Caldow and the pair hit it off immediately. Indeed, they played together 12 times for Scotland, making Mackay the 40 times capped Caldow’s most frequent international partner.

Caldow had a story of, as Scotland captain, passing-out the ‘fan mail’ when the national squad was in a training camp at Largs, and finding one addressed to “Donkey Mackay’ (sic). “This lassie must have seen you playing Dunky,” quipped Caldow, who, in reality, rated his Celtic pal very highly as a player.

But, if things were going well with Scotland, all was not well at Celtic Park, where, following the 1957 League Cup win, the side struggled to compete with Rangers, Kilmarnock and Hearts, who were then the top teams.

Bertie Peacock left the club and Mackay was appointed team captain in 1960, leading them to the Scottish Cup final of 1961, where they lost to Dunfermline after a replay. Indeed, along with 1940s goalkeeper Willie Miller, Mackay shares the “distinction” of having won more Scotland caps than medals as a Celtic player.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1963 he lost the captaincy to Billy McNeill, then, after injury he lost his first-team place, partly because, it is rumoured, manager Jimmy McGrory and chairman Bob Kelly – who picked the side – did not like Mackay’s attacking sorties up the wing. He was replaced by Ian Young, who ironically predeceased Mackay by less than two weeks.

In November, 1964, he left Celtic for Third Lanark. This is one of Scottish football’s great “what-ifs,” maybe, had he hung on until Jock Stein returned in February 1965, he would have regained his place. Stein certainly preferred attacking full-backs.

Third were starting to implode and at the end of that season, he jumped ship – accepting an offer to join Melbourne Croatia, who were spending big in a bid to become the top side in the Victoria League, with the Scottish internationalist just one of a host of new signings.

In Australia, he was an instant success. He was made captain, and won the Player of the Year title in his first season. He led Croatia to several trophies, including a league and two cups treble in 1972, but the club fell foul of Australian Soccer financial rules and collapsed. Mackay returned to Scotland for two seasons, working as a book binder, coaching juniors St Anthony’s.

His first marriage, when a young man, had failed. But while, back home, he took time to marry Marilyn, before, in 1974, Perth Azzurri, in Western Australia, offered him a player-coach role.

He led the Azzurri to back-to-back league titles, then accepted an offer to return to Melbourne, to Essendon Lions, as Croatia had now become. Here he found success as a league-winning coach, before winding down his active involvement in football with South Melbourne Hellas. While with Hellas, he coached a Victoria Select to victory over a touring Dundee side.

Melbourne clearly suited Mackay. In his first spell with Croatia, he turned down the chance to join Pele at New York Cosmos, while, after working with a firm which made surgical equipment, his non-football working life turned full circle when he joined Transfeld Ship Builders, who build frigates for the Royal Australian Navy, as a Senior Procurement Buyer – the post he filled until his retirement.

He and Marilyn, who survives him, had two children, daughters Shona and Elissa. Duncan is also survived by son Duncan Junior, from his first marriage, who also lives in Australia. Paul, another son from that first marriage predeceased hisfather.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn retirement, Mackay enjoyed his steaks and listening to his music, in particular the Beatles, Barbra Streisand and Tony Bennett.

Dunky Mackay was Celtic’s Player of the Year in 1963, and Man of the Match when they played Real Madrid at Parkhead in a friendly.

Sadly, he never had the medals to show for playing at a low point in the club’s history. However, on the other side of the world, he finally won a few gongs, forged a good reputation as a coach, and perhaps showed Scottish football what they lost when they allowed him to leave.

MATTHEW VALLANCE