Obituary: Douglas Hall OBE, keeper who gave Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art its international reputation

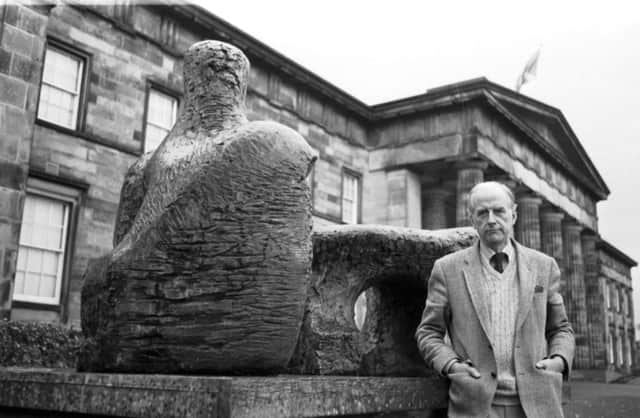

Douglas Hall, the first Keeper of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art from 1961 to 1986, has died aged 92. He established the Gallery’s international reputation and made a lasting impact on the arts in Scotland and beyond. His independent and sometimes idiosyncratic taste helped shape a collection which today would cost hundreds of millions of pounds to reassemble.

The National Gallery of Scotland and its sister institution, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, opened in Edinburgh in 1859 and 1889 respectively. Calls for a gallery of modern art were made periodically, but it only became a reality in August 1960 when the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art opened at Inverleith House in Edinburgh’s Royal Botanic Garden.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn its first year, David Baxandall, Director of the National Galleries, was in charge, assisted by Colin Thompson, Keeper at the National Gallery. Hall took up the post of Keeper at the Gallery of Modern Art in November 1961. The National Gallery and the Portrait Gallery did not collect work by living artists. Although a few exceptions had been made (notably Alexander Maitland’s gift of a Blue-Period Picasso in 1960), when Hall arrived the Gallery’s collection of modern art consisted largely of prints. There was no library and, for the first few months, no office: he was given a chair at the other end of Thompson’s table. It being winter, a gallery attendant would come in periodically to put coal on the fire.

Once an office had been made on the top floor of Inverleith House, Hall encountered a number of competing pressures that were to remain constant throughout his Keepership. His acquisition grant was just £7500 per annum, creating a brake on grand ambitions. He also had pressure from Baxandall and the Trustees, who recommended acquisitions on a regular basis and sometimes quashed his own choices.

There were some who thought the Gallery should focus on Scottish art. Baxandall had attracted criticism with the Gallery’s first major purchase, an outdoor bronze by an Englishman, Henry Moore. There was pressure from some quarters to buy from the Royal Scottish Academy shows and from others to focus on contemporary art. Throughout his tenure, Hall had to steer a path through these competing and sometimes hostile voices, and do so on his own: for the first ten years he had no assistant.

Douglas Hall was born on 9 October 1926, to Scottish parents who had moved to London 18 months earlier. He was the youngest of five children. His father was a civil engineer and chief draughtsman to the Port of London Authority.

Hall went to University College School in Hampstead. He was called up in 1944 and worked in the Intelligence Corps until 1948. He had intended to train as an architect but when a friend suggested a career in museums, Hall liked the idea and enrolled at the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. Anthony Blunt was then the Director.

He graduated in 1952 and married a fellow student, Elizabeth Ellis. In March 1953 he was appointed Keeper of the Rutherston Collection of British art which was run by Manchester Art Galleries. In 1957 he became Keeper at Manchester City Art Gallery. There was little glamour in museums at the time: for exhibitions, he hired a van and collected the loans himself. He became Deputy Director in 1959.

Hall believed he got the job in Edinburgh because few, if any, other Scots applied and he had no baggage associated with the Scottish art scene, such as it then was. Inverleith House was, and still is, a perfect venue for modern art, but its size was always a problem. The narrow entrance meant that large works, which were becoming the norm in the 1960s, would not fit into the building. A Jackson Pollock painting was turned down because it was a couple of inches too big.

He gradually built an impressive collection. He visited Joan Eardley in Catterline and bought her work. When French art was still the gold standard of modernism, Hall showed an unusual passion for German art, acquiring major works by Kirchner and Nolde and a superb landscape by the Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler. It is still the only Hodler in a UK public collection. He bought a major painting by Jean Dubuffet in 1963, before the Tate had one. The Gallery’s files are full of his beautifully crafted letters, typed by a part-time secretary. He did what several departments now do.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTemporary exhibitions, often organised by the Scottish Arts Council, were shown on the first floor, but they were never Hall’s first priority, partly because of the limited space.

An avuncular, softly spoken man of keen intelligence, great courtesy and negligible ego, he loathed pomposity, arrogance and hype. His stubborn, independent spirit was his Achilles heel, in that he never bought work by giants such as Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol and Lucian Freud. It was partly that he was always searching for the perfect work, but it is also true that celebrity turned him off. Nothing depressed him more than visiting a museum and finding it full of works by the same artists he had seen in every other museum. He fought against orthodoxy by acquiring works by Polish artists who had been (and still are) ignored. He discounted Charles Rennie Mackintosh because he was so well represented in Glasgow, yet he acquired masterpieces by less obvious artists such as RB Kitaj, Marcel Broodthaers and Duane Hanson.

Hall masterminded the Gallery’s move to much larger premises, in the former John Watson’s School on Belford Road, Edinburgh, in 1984. In the years leading up to the move, Hall was given a much larger acquisition budget, enabling him to buy outstanding works by Picasso, Mondrian, Roy Lichtenstein, Louise Nevelson, Fernand Léger, Otto Dix and Balthus, among others. In 1985 he had triple by-pass heart surgery. Although he made a full recovery he was, to his annoyance, asked to step down in 1986, aged 60. He was awarded an OBE for services to the Arts in 1985 and an honorary doctorate by the University of Stirling in 2009.

Hall retired to an old manse in Morebattle, in the Borders, with his second wife, Matilda Mitchell, whom he had married in 1980 (he divorced his first wife in 1978). He wrote a major study, Art in Exile: Polish Painters in Post-War Britain in 2008, for which the Polish Government awarded him the Gloria Artis medal. He enjoyed gardening and singing with several choirs. Despite failing eyesight and poor hearing, he continued to attend openings in Edinburgh until recent months. His delight in looking at pictures and talking about them never waned.

Douglas Hall died peacefully at Kelso Cottage Hospital. He is survived by his wife, Matilda Hall, a son and daughter from his first marriage and grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Patrick Elliott