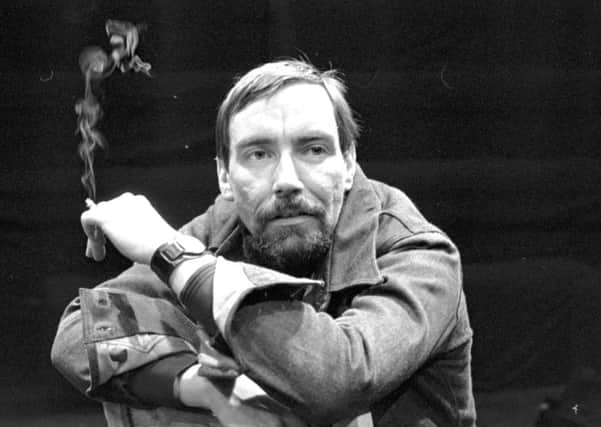

Obituary: Donald Campbell, playwright, poet and historian, transformer of Scottish cultural community

Donald Campbell, who has died in Edinburgh aged 79, was part of a generation of writers who, from the 1970’s onwards, lit up the Scottish literary and theatre scene with an impressive new sense of ambition and confidence, writing contemporary drama and poetry in a distinctively Scottish voice that spoke for a modern nation rediscovering its own history and potential, at a time of huge social change.

In Edinburgh at the turn of the 1970s, Campbell was a young bank official by day, but by night a key figure in the city’s flourishing poetry scene, appearing regularly at spoken-word events staged by the radical writers’ collective The Heretics. Campbell’s first two collections of poetry, published in 1971 and 1972, won great acclaim, particularly from enthusiasts for new Scots-language writing, and led to his appointment to the new post of writer in residence in Lothian schools, which he occupied from 1974 to 1977; a short film called Giving Voice, produced by the Scottish Arts Council in 1976, shows Campbell passionately engaged in persuading Edinburgh secondary school students that poetry-making is for them, and should be part of their lives.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe poet and novelist John Herdman, who introduced Campbell to The Heretics, describes how the quietly-spoken poet also soon emerged as a charismatic performer of his own work, with an obvious gift for creating character and dialogue; and no-one who knew his work was surprised when, in 1976, Campbell and his friend actor-director Sandy Neilson came together to create a sensationally successful production of his first play The Jesuit, about the imprisonment and execution of the 17th century Scottish Catholic martyr Saint John Ogilvie.

Although it was produced by The Heretics, Campbell’s big, vigorous drama – touching on the still-controversial theme of Scotland’s sectarian history – was welcomed into the Traverse by the theatre’s then artistic director Chris Parr, a powerful champion of new Scottish playwriting who viewed Campbell’s voice as an essential part of the new Scottish repertoire he was building. “Almost all the playwrights we were working with at the time were from west central Scotland,” says Parr. “It was Tom McGrath, Billy Connolly, John Byrne, Marcella Evaristi. But Donald always seemed to me a true Edinburgh playwright, with that different, very powerful voice, and a real gift for tragedy, rather than comedy.”

The Jesuit was followed, in 1978, by Campbell’s second play Somerville The Soldier, and in 1979 by The Widows of Clyth, based on the true story of a Caithness fishing disaster passed down through Campbell’s mother’s family. These three huge successes formed the basis for a theatre career that continued into the new millennium, as well as of Campbell’s long award-winning career as the writer of more than 50 radio plays; and although Campbell turned back to poetry in the last decade of his life, his relationship with theatre, as a writer, director, adaptor, historian, and stubborn dissenter from establishment views of the art-form, remained one of the central passions of his life.

Donald Campbell was born in Wick, Caithness, in 1940. His father was an Edinburgh man who eventually became a telephone engineer, his mother a Caithness woman working in Edinburgh; and at the outbreak of war in 1939, the family returned to Wick. They came back to Edinburgh, though, in time for Donald to start school at Craiglockhart Primary in 1945; and when he left Boroughmuir High School in the mid-1950s, he became a trainee at the Bank of Scotland, spending some years working in London, where he began to write poems.

He returned to Edinburgh, and in 1966 married Jean Fairgrieve, a civil servant who later became a schoolteacher; their son Gavin was born in 1968, by which time Campbell was submitting poems to publications including John Herdman’s literary magazine Catalyst. It wasn’t until he became Lothian schools writer in residence in 1974, though, that he was able to give up the bank job, and become a full-time writer.

After the huge success of his three major plays of the late 1970s, Campbell became writer in residence at the Lyceum Theatre from 1981 to 1983, and later held similar posts at the University of Dundee, in Perth, and at Napier University. In 1980, his popular musical drama about the history of Edinburgh’s High Street, Blackfriars Wynd, was performed on the main stage of the Lyceum, and in the late 1980s, he co-founded the Old Town Theatre Company, working at the Netherbow (now the Scottish Storytelling Centre) to create community-based drama of the kind he loved. He was also a passionate historian of theatre. His history of the Lyceum Theatre, A Brighter Sunshine, was published in 1983, and was followed in 1996 by his history of Scottish theatre, Playing For Scotland.

“Donald was a man of the left,” says his friend John Herdman, “and a believer in Scottish independence; but I think he preferred to express those ideas through his character of his work. When The Heretics started up in 1970, there were many people writing a kind of synthetic or invented Scots, based on their political convictions. But Donald’s Scots was the real thing; it was what he heard on the streets and in the pubs and on the football terraces. He once told me in an interview that “the only thing for me is sound”; and if a line sounded better to him with an English word than a Scottish one, then he would use it.”

Campbell also told Herdman that it was the underground movement in poetry and literature that really commanded his loyalty; and although Campbell’s work and life seem far from counter-cultural imagery often associated with the 1960s underground, his career was nevertheless shaped by an uncompromising creative radicalism and integrity that may have limited his success within the conventional structures of theatre, but left him with a solid sense of pride in his own achievements.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Donald hated snobbery and pretension, both intellectual and social, and wanted a classless theatre,” says his long-time friend and collaborator Donald Smith, artistic director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre. “He was instrumental in putting socially authentic Scots language on to the main stage, and giving voice to aspects of Scottish history and experience that had not been heard there. That was the source of his big impact in the Seventies. And even towards the end of his life, when he was no longer working in theatre, he looked back with enormous pleasure on his theatre work. He felt, I think, that he had achieved what he had set out to do.”

Donald Campbell is survived by his wife Jean, his son Gavin, his daughter-in-law Margaret, and his grandsons Lewis and Andrew; and by a Scottish cultural community that he helped to transform, as part of a great generation that believed in giving a voice to all the people of Scotland and their stories, and in the power of those voices to generate real change, both in individual lives, and in the wider world.

The film Giving Voice can be viewed here, as part of the National Library of Scotland video archive. https://movingimage.nls.uk/film/3269

JOYCE MCMILLAN