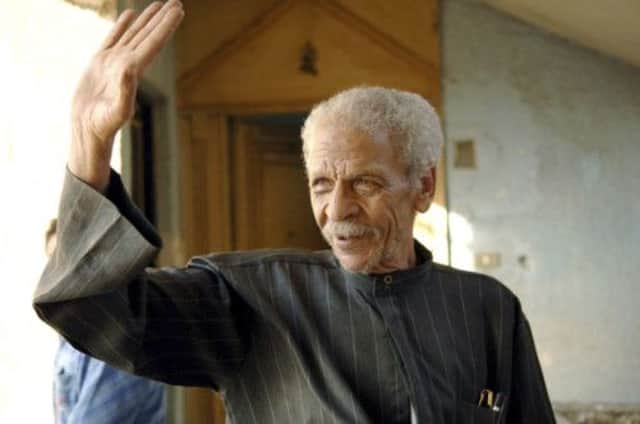

Obituary: Ahmed Fouad Negm, poet

Ahmed Fouad Negm was one of the foremost Egyptian poets of the 20th century. Imprisoned under both Nasser and Sadat he wrote colloquial poems that deftly satirised his country’s leaders and spoke for the aspirations of the voiceless. He reached the height of his popularity in the 1970s performing with a blind singer and oud (Arabic lute) player called Sheikh Imam, who provided the powerful rhythms to Negm’s subversive wordplay. Recently, these songs have provided much of the soundtrack for the revolutionaries in Tahrir Square and still speak directly to new generations.

Negm was born in a small village in the Egyptian Delta and given the middle name Fouad after the king at the time. He later portrayed his life in his village as that as a typical Egyptian fellah (peasant).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis mother could not read or write and the number of his siblings ran well into double figures. Then, when he was still in primary school, his father, who was a police officer, died and the six-year-old Negm was sent to an orphanage in the Delta town of Zagazig, where he stayed until 1945.

When he was old enough Negm travelled to Cairo with his brother Mohammed, who worked in a printing business. He arrived just in time to get his first taste of street politics when he took to the streets in the 1946 protests against British control of Egypt.

In the next years he worked in a number of menial jobs in the capital and cities on the Suez Canal but never kept far away from politics.

His first encounter with the communist party came in 1951 during the waves of protests that swept Egypt. When he and the party members started talking about books Negm said proudly that he had read 178 detective novels. They were not as impressed as he had hoped and suggested he read Maxim Gorky’s The Mother, which he says put him “on the track to true liberation”.

Yet, it was not until his first spell in prison from 1959 to 1962, on fraud charges trumped up by corrupt co-workers, that he began to write poetry. Incarceration gave him a new view on the world and its power dynamics. He began to express his feelings about the down-trodden which would be central to his poetry for the rest of his life.

Leaving prison he had the encounter that set its career on a new course. In a cafe in Cairo he saw the oud player Sheikh Imam performing and went to talk to him. They hit it off instantly and Imam’s music turned out to be the perfect medium for Negm’s vernacular poetry.

After Egypt’s defeat by Israel in 1967 Negm and Imam’s blend of irreverence to the powerful and support of the underclasses became the anthems of left-wing protest. But popularity came at a price and Negm spent much of the next 25 years on the run or in prison.

This culminated in an 11-year sentence in 1978 for performing a poem that made fun of then president Anwar Sadat. Negm spent the next three years on the run and was not arrested until 1981.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBooks of Negm’s poetry were banned but songs like Guevara is Dead, Beans and Meat and Courage is Courage were spread by bootleg cassettes or in private concerts.

Marilyn Booth, professor of Arabic literature at the University of Edinburgh, described such a concert. Sixty people crammed into her tiny Cairo flat in 1980 to hear Sheikh Imam sing these contraband hits.

Negm could not be present because he was on the run from the police but Imam gave an incredible concert. Then at the end of the night, as was Negm and Imam’s custom, he did not accept money but was paid with a kilo of kebab. The songs became so popular that one judge, before giving his sentence, asked the duo to do a rendition of one of the hits Haha’s Cow. By the end of the number the judge was in tears.

Negm’s irreverent words poked fun at elites but were always rooted in the long suffering of the Egyptian people. “They are wearing the latest fashions while we are sleeping seven in a room… They fly in aeroplanes while we die in buses” he writes in Who are They and Who are We.

After his 11-year prison sentence his poetic output slowed. He, nevertheless, continued to be an influential social commentator in newspapers and on television, where he shocked presenters with his blunt appraisals of public figures and filled Egypt’s living rooms with bleeped-out profanities.

He also composed his three part autobiography called Al-Fagoumi, after his long-standing nickname.

A bent towards self-mythologising and a sharp sense of humour mean that Negm’s personal life is hard to pin down. Depending on who is talking, he had between five and eight wives who included the singer Azza Balba, the author Safinaz Kazem, the actress Sonia Mikio, Omayma Abdel Wahab, and Fatima Mansour. Three daughters survive him: Nawara, an activist, Afaf and Zeinab.

When the revolution began in 2011 it revitalised Negm and exposed a new generation to his poems, which were sprayed across Egypt’s walls and chanted in its squares.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis year, Negm was due to be given the Prince Claus Award “in appreciation of his literary contributions and his unwavering advocacy on behalf of the poor and the disenfranchised” on 11 December in Amsterdam. The ceremony will go ahead in his honour.

Despite his widespread recognition he never lost his rebellious spirit. When the presenter of a talkshow in 2013 discovered to his surprise that Negm had given up smoking hashish he asked: “Is the world better with hashish or without it?” Negm responded: “It’s better with revolution.”