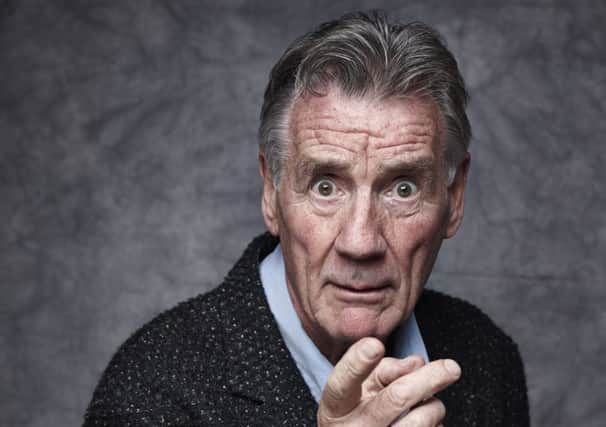

Michael Palin on his diaries, and being nice

MICHAEL Palin is a total diva. He kept me waiting endlessly for him at his club, the Union in London’s Soho, and then, such is his overweening narcissism, he threw a hissy fit and refused point blank to have his photograph taken wearing his spectacles.

This isn’t true of course. Palin is one of the nicest, most obliging interviewees you could wish to meet, but he asked me to write the above because sometimes he fantasises about being less nice, about sitting down and writing a total bitch-fest of a How To Be A Diva self-help book.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’d like to write one of those,” he says. “How to be a diva. Be late, be difficult, that kind of thing.”

When I laugh, he says indignantly: “Well, I was late today.”

I hadn’t noticed.

“Yes! Nearly ten minutes!” he says gleefully. Then spoils it. “I’m terribly sorry about that.”

It won’t work. Palin as nasty just won’t wash. The 71-year-old was always the “nice” Python, a disarming foil to John Cleese’s towering rage. And rather than penning venomous self-help books, the nation’s favourite television traveller is more likely to be asked to lead us from the comfort of our armchairs on another journey where we can enjoy his up-for-anything, bemused take on his encounters from Peru to Penang.

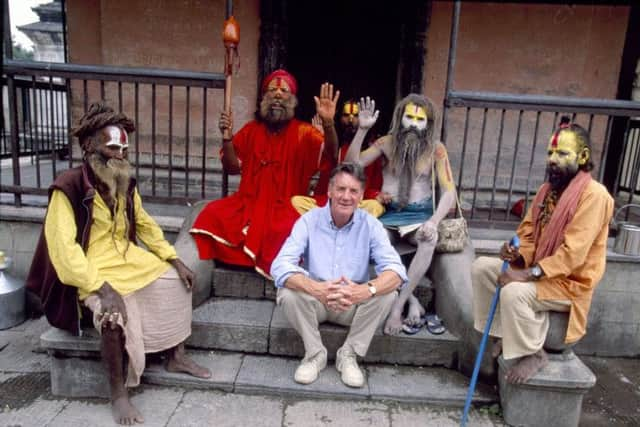

For 25 years Palin has been criss-crossing the globe to make nine travel series, starting with Around The World In 80 Days, then Pole To Pole, Full Circle, Michael Palin’s Hemingway Adventure, Sahara, Himalaya, New Europe, Brazil and 80 Days Revisited.

Now a much shorter journey is on his autumn itinerary, as he tours his first one-man stage show, Travelling To Work, from Inverness to Southsea. The 21-date tour includes Edinburgh this month, and celebrates the publication of the third volume of his diaries. The years 1988-98 coincide with his career branching out in several directions, into the TV travelogues, writing a novel called Hemingway’s Chair, expanding his film career with roles in A Fish Called Wanda and American Friends, writing The Weekend, a play that received mixed reviews in the West End, spending a week filming with Meg Ryan in You’ve Got Mail, playing the part of a benevolent writer, only for it to be left on the cutting room floor. Through it all runs his continued friendships with the Pythons, a reunion with whom finally transpired this summer with their O2 performances.

Palin had made various attempts to write diaries when he was at school, “but they always petered out mid-February”. It was after he quit smoking when his first child Tom came along in 1969 that he cast about for another challenge on which to flex his newly discovered willpower.

“I’d always wanted to keep a diary, so I started one. This was a month before our first Python meeting, so luckily I recorded those years too.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPalin is the only Python to write a diary, keeping track of the ins and outs of one of the world’s legendary comedy acts.

“Well, Terry [Jones] says he’s got a diary, but I haven’t seen it,” says Palin. “He says it’s so rude. But no-one’s kept a diary so assiduously as I have.”

Along with the travels and work meetings, the roll call of celebrities from David Bowie to the Queen (she fails to recognise him the first time they meet, but he’s later awarded a CBE), is the backdrop of Britain between 1988 and 1998, revealed slowly, from the Lockerbie bombing to the fall of Margaret Thatcher, tapped out daily by Palin.

“What I like about diaries is they’re about days, not about a life. There is no consistency, but it’s fascinating because it was written at the time.

“The diaries cover an extraordinarily busy time of my life. I was trying things I’d never done before, pushing myself beyond the predictable to novels and plays and a whole new career as a television traveller. I like to think that the Travelling To Work tour is in the same spirit of adventure and experiment. It will be my first solo tour and a chance to meet audiences and talk about the only consistent thread in my working life – the irresistible urge to do something completely different.”

The show covers 25 years of travel and 50 years of radio, television, books and film. How does he fit this all into one show?

“It’s jolly difficult. It’s going to be about three hours, but we’ll see, I don’t want to put people off. Basically for the first half, the stories are all occasioned by Basil Pao’s wonderful photos. The second is about comedy, stories, films, books, and I want to get questions from the audience too.”

Palin never intended to publish the diaries, but then it was suggested in 2005 that he share these things while he was still alive. This, however, lays him open to scrutiny from those who may dispute his account of events.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All the Pythons do that. They say, I don’t remember that. They don’t remember a thing! They all complain, nicely. But I’m not nasty anyway. I am critical, of myself most of all. And every day isn’t a happy day, so the negatives have to be in there too.”

With grandchildren to play with these days, Palin’s appetite for long-haul travel is diminished and he professes to be content to stay at home in Gospel Oak, Camden, north London. He still lives in the same Victorian terraced house he has lived in since 1968 with his wife Helen, a bereavement counsellor, although they’ve since bought the two houses next door too.

“We’ve never moved because my wife and I are fairly placid types. I think a base is very important. You can put up with any chaos in travel if you come back and know where things, and people, are.”

He first spotted Helen when he was 15, from the window of a Suffolk B&B he was staying in with his family. “There was a whole line of them going to the beach and she was making it clear she didn’t want to go. It was her mischief and her humour. That’s what attracted us to each other.

“I’m almost certain I won’t do long journeys again, because I think I’ve exhausted the formula. Also I’m in my seventies and we’ve got grandchildren, and the idea of being away from home for four months doesn’t really appeal. If I do make programmes, they will be simpler, shorter, hour-long about a place or an artist.” Palin’s documentaries about the artists Anne Redpath and Andrew Wyeth were well received. He is also tempted to go back to his pre-Oxford roots, when he trod the am dram boards at home in Sheffield and do some straight acting. The son of a steel mill manager, he was sent to Shrewsbury school then studied history at Oxford.

“Time for your Lear, Michael,” he hams. “I think my appetite for travel is weaker now, because I have seen an awful lot in those 25 years of travel and met so many people. I’d almost just like to spend the time remembering, reflecting, instead of always looking for something new.”

Yet despite being content at home, Palin is still endlessly curious about other people and places. It’s this infectious enthusiasm and downright niceness that recommends him as a pleasant travelling companion. In the beginning, however, he writes in the diaries that these very qualities might be his downfall in front of the camera.

“My contribution, I think, will not be precision, analysis and revelation, but honesty, directness, openness and enthusiasm… Is this enough? I think of seeing all this through Jonathan Miller’s and Alan Bennett’s and Terry Gilliam’s eyes and how much sharper and more original it might all be. But the fact is I have the easy, untroubled character that will, I hope, make me an interesting victim rather than a cool observer.”

Is this why he thinks people like him?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That’s very hard for me to pin down. What viewers often say is we feel you take us along with you. I’m shown travelling warts and all, stymied by the language or ill after the food or lost in the middle of the desert, rather than being a presenter who just delivers very smoothly their material. So there’s an element of accident, which people like. They think I would be a good person to travel with because I’m very curious. I like food and drink, I’m quite adventurous and I like company.”

Does he ever think, “Why am I doing this?” Why is he swimming with sharp-toothed pink dolphins in the freezing cold water, cooking eggs in a volcano, crashing a Boeing 737, making whoopee cushions out of sheep’s scrotums, delivering a crocodile?

“Quite often. The number of times I’ve shouted at the director, ‘Why am I doing this, what’s the point?’ Then afterwards you feel, ‘Oh God, I’m glad I was made to do that. I would never do it myself’.”

No matter how uncomfortable, Palin tries never to complain on camera. “You’ve got to be careful because people think, well, you’re a lucky bastard. You might have landed on one of the worst streets in the world, but at least you’re travelling. I’m prone to whining but try not to because there’s so much to see and do out there.”

He’s also game enough to do things just because the cameras are rolling.

“I’ve eaten and drunk things that were strange, including a pink potion given to me by two old ladies in Peru. It was quite nice. I had about three or four slurps. Later I found out it was a special wine, fortified by saliva. You’ve got to have a go. And I had some camel kidney when I was in Algeria and that provoked the most terrible illness.”

Despite the pages of his diary being filled with meetings with everyone from Princess Diana to Salman Rushdie and numerous film stars, musicians and writers in between, Palin prefers ordinary people to celebrities.

“I feel that celebrity just gets in the way. It’s an accident. Many, many people are just as talented but haven’t been noticed. Ordinary people are more open about their lives. That’s where the best encounters work, where we can find something out about each other.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I remember being on a Tibetan plateau and a yak herder took me to his yurt. His wife was making butter and it was smoky and his children were just like my children, one shy, one sucking up to the stranger. Neither of us knew the other’s language, but there was a connection. I felt reassured by that universal spirit which constantly surprises me, how people in the most grim situations are welcoming to strangers.”

One notable celebrity exception for Palin was the Dalai Lama, whom he met making Himalaya.

“He was terrific. The first thing he did was to shake hands with the crew – no one ever does that – and he was extraordinarily generous with his time, really enjoying himself. You got that he was a man millions worship and follow, but he’s also just a guy talking about his travels, and my travels. We talked about jet-lag and that kind of thing.”

What were his top travel tips?

“It was to do with digestion. Get your bowels in order. He does brighten your day, make you laugh.”

Is he a Python fan?

“I don’t know. He’d seen the travel programmes on the BBC though. He said, ‘I want to come with you’.”

Travels with Palin and the Dalai Lama?

“Yes, but we’d just laugh all the time. You wouldn’t get any sense out of either of us.”

What unites the dead parrot salesman and the cross-dressing lumberjack with the man who wrote Hemingway’s Chair and the headmaster in GBH?

“You could say they’re all slightly against the system. The man selling the parrot has sold someone an obviously dead parrot, and the lumberjack would get his head sawn off in British Columbia for wearing women’s clothes. Hemingway was always trying to carve out his own road. The GBH headteacher was an individual who fought on despite others too.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo they’re all rebels. Is that how he sees himself? “Yes. Slightly outside the system, not conformist, although I’m very conformist in lots of ways. I believe in people being nice to each other and good manners – life’s better that way. But I do always like to look at the odd, the unusual. Which is why I’ve never made up my mind what I want to do in life.

“I’ve had an amazing, very fortunate life where I’ve been pushed into things by friends and held up by a safety net of comedy, acting and all sorts of stuff.

“I never expect anything from what I do. I don’t think, well this is going to be a success. I’ve never felt that, from Monty Python, right through to even a great film like A Fish Called Wanda. That felt very risky at the time.”

Wanda went on to be a massive hit, and Palin won praise for his portrayal of Ken, a stammerer, drawing on his father’s affliction.

“I don’t think I could have done that part if he’d still been alive,” he says. “It was the elephant in the room, but we didn’t talk about it. Obviously he’d tried therapies and they didn’t work so it would have been mean to say, ‘Can you not stop that?”

“I suppose, with the travel shows, once I’d established that I could pull in a good audience, I felt I didn’t have to prove myself as a traveller, but I never took anything for granted.”

The much anticipated and rapturously received Python reunion that took place this summer – did that happen because they were all feeling strapped for cash?

“Yes, the impetus to get together was to sort out Python’s finances. There were individual demands, John Cleese in particular with his ludicrous divorce settlement, but also Python was known as a brand around the world, but wasn’t doing much. There wasn’t much money coming in and we were all wondering about the future. Then we met Jim Beach, who manages Queen and was a friend of Eric Idle’s at Cambridge, and he suggested a reunion. He said three nights at the O2 Arena would pay off our debts. And our jaws dropped. In 15 seconds, less than that, seven and a quarter, we said yes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“So the money brought us together, but I suspect the real reason we did the reunion was that we all wanted to work together one more time. The timing was right, everyone wanted to do it, and the demand for us to get back together was extraordinary.

“The O2’s a big place, so it was alarming, but after the first night, we knew we could do it. Everybody had a good time, for ten shows, and that was enough. Beyond that we’d have got a bit bored. So we won’t do any more big shows. That was it.”

When we meet it is only a couple of days since the suicide of Robin Williams, who Palin mentions in the diaries.

“Yes we had dinner a couple of times. He was quite a frightening person in a way because he was so incredibly brilliant that you couldn’t have an evening’s conversation. He had a wonderful, great gift. When he started you didn’t know where he was going to go. His mind was like a library, pulling out references. He could create a comic world monologue. Peter Cook could do it too; people like that are my heroes.”

Palin has personal experience of the devastation of depression. His elder sister Angela committed suicide in 1987 after her own struggle with the condition.

“In the aftermath of Williams’ death, people talk about depression and the fact we find it difficult to talk about, but now it’s much easier to discuss the subject than it was. Robin Williams had therapy and was able to say he was an alcoholic, but what I learned about depression from my sister is that the most difficult time is when everything is going fine, and then a little thing happens and you realise it’s still there. It never goes away. It’s the black dog, as Hemingway and Churchill called it.

“Towards the end, Angela seemed engaged in life. She would go off and play tennis, and a couple of days before she died I saw her, and she was great company. We went to an Afghan restaurant and to see a film. She was taking things in, but clearly had plans. Maybe she was happy because she knew she was going to end it all. It’s a disease,” he says.

Did this bring him closer to his mother, Mary, whose tiny, wry figure loomed large in the diaries and in Palin’s life until her death in 1990.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It didn’t make a huge difference. I’ve never been sure about my mother’s attitude. She kept stoic about the death of her daughter. Maybe she knew more about her condition than I did. I wanted more from her, I think. We didn’t discuss family emotions much, it’s a shame. But that generation of people had been through the Second World War and the Depression. They didn’t have so much time to experiment with ideas and philosophies as we did in the 1960s.”

Apparently sane and down to earth, despite the surrealism of Python, Palin has never felt the need for therapy himself. “I understood how my sister felt, but I’m eternally sunny and jolly,” he says.

What about Cleese, whose various therapies are reported throughout the diaries. Does Palin think it has helped him?

“That’s a leading question. But imagine what he’d be like if he hadn’t had it!” Realising he’s on the brink of perhaps being indiscreet, he heads off to have his photograph taken, whipping off his glasses and patting his hair as he goes.

Michael Palin, what a diva.

Twitter: @JanetChristie2

Michael Palin: Travelling To Work, Live Tour, tickets start from around £34.25, Friday, Theatre Royal, Glasgow (www.atgtickets.com); Saturday, Aberdeen Music Hall, Aberdeen (www.aberdeenperformingarts.com); 14 September, Eden Court, Inverness (www.eden-court.co.uk); 16 September, King’s Theatre, Edinburgh (www.edtheatres.com), for further information see www.palinstravels.co.uk)

Travelling To Work: Diaries 1988-98, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, are published on Thursday, £25 hardback, £12.99 e-book (www.orionbooks.co.uk)