Living with the aftermath of suicide

I remember sitting in my Edinburgh home that Saturday afternoon waiting to be driven down to the family farm in Lancashire, where she had died, feeling icy and shaky and with a high-pitched ringing in my ears. I was there but I was not there.

When we arrived at my dad’s house, beside the farmhouse where Tricia had died, I was worried my 87-year-old father would not have survived the shock of finding her body. But he had survived. He was sitting in his armchair crying, repeating: ‘She didn’t know what she was doing, poor lass.’ Something he said again and again over the following days and weeks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was important for me to see her, and so my older sister, Elizabeth, and I went to the mortuary as soon as it opened the following Monday morning. I stared at her body in disbelief and touched her chilled hand and asked her: ‘Oh, Tricia, what have you done?’

We had to wait for a post-mortem to be carried out. This was hard because following her unnatural end we wanted to give her as dignified a funeral as we could, as soon as we could.

Every detail seemed of enormous importance. I felt guilty that we had not prevented her from dying and so getting these final details right was very significant. We covered her coffin in red roses. We chose Bach and Alison Krauss for the music. We filled her coffin with photographs of her dogs, cats and horses.

There was a great desire to try to understand what had happened and we had many round-and-round conversations trying to work out what we could have done differently, what we could have said differently. What clues had we missed? How could we have stopped this catastrophe occurring?

Had we appreciated the pain she was in? Had we blamed her for being ill? Any memories of losing patience with her were particularly painful. There was no putting this right. The very worst had happened and could not be rectified.

She left no suicide note or message for us. But what she did leave was a lifetime of diaries dating from when she was 14. The police checked for any clues as to her state of mind in the final days but found nothing helpful. I said I could not read the diaries – I was too frightened of finding page after page of black despair or, worse, blame for us, her family. My older sister took them home and stored them in her attic.

We hoped that the inquest at Lancaster Coroners Court would provide us with a sense of closure, but it didn’t. The aim of the inquest was to answer the questions Who died? How did they die? And when did they die? There was to be no apportioning of blame and so we felt our questions to the mental health services went unanswered. Why had she not been sectioned under the Mental Health Act when the consultant psychiatrist visited her at home on the day she died?

The answer came: Her life had not been in danger. I felt like banging the table in frustration. How could the consultant say that when within hours she was dead? But the inquest was not to apportion blame, repeated the coroner, and moved the proceedings on. We felt a deep anger about this.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI never felt anger towards Tricia though. I was warned that I would, but it never came. How I regretted that she had taken the decision she had, but I could not blame her for it.

Six months after she died we decided to begin to dismantle the contents of the family farmhouse where she had died, and we three sisters and our father had all been born. This was an immense task, made more complicated because everything that had once belonged to Tricia was imbued with great meaning.

We picked our way through stacks of papers, old letters, sheet music, and her paintings and drawings. Not able to dispose of many items we got an old box and, calling it a memory box, we filled it with memorabilia.

We adopted as many of her belongings as we could. Altering her dresses to fit, using broken beads to make Christmas decorations, framing her watercolours.

Things that could not be donated or recycled or used we burnt on an enormous bonfire in the orchard. This was in effect a funeral pyre that burned all day Saturday and into the next day. The fire felt cleansing as did creating a noise in the empty farmhouse. I rooted through her old vinyl records and played Roy Wood’s Look Thru the Eyes of a Fool at full blast to move the air in the farmhouse just a little.

Two and half years after she died I was still searching for answers to how it had happened and decided the time was right to read her diaries. I took them with me on a writer’s retreat to Hawthornden Castle in Midlothian and spent the first week there reading through from start to finish.

I was hugely relieved to find no blame for us in there. In fact, to find affectionate references to myself – which I read over and over again – and moments of joy. It was as though Tricia was there with me in the castle and when she mentioned a song she was listening to, I put it on my iPod and felt I was having a conversation with her.

I decided to use the diaries as a basis for a memoir called When I Had a Little Sister, in an attempt to dig as deeply as I could into Tricia’s story and work out why it had ended as it did. I left Hawthornden Castle after a month with the first 30,000 words written.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWriting the book was cathartic and felt like a joint enterprise with Tricia. It was a sad moment when I finished and knew that joint venture was done.

For months after Tricia died, I cried every day. As the time passed, sometimes weeks went by when I didn’t cry – but I still think of her every day. Anniversaries, birthdays and Christmases are particularly hard – especially as she died in the run-up to Christmas.

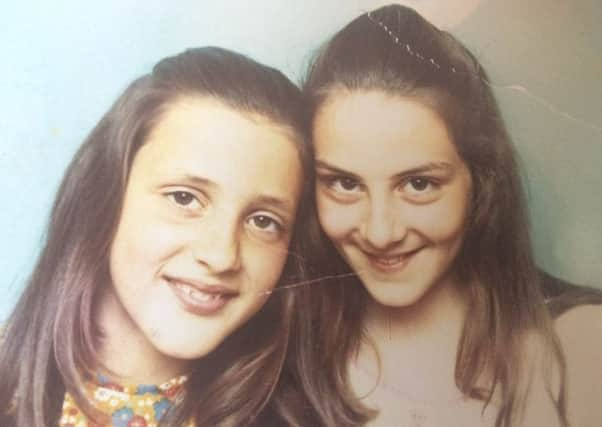

Over time though we have got better at remembering the good times with Tricia. Laughter is healing and Tricia loved a good laugh herself when she was well. So my memoir is not a litany of despair but also contains stories from happier times of our childhood growing up on a Lancashire farm in the 60s and 70s and good memories from when I had a little sister.

When I Had a Little Sister by Catherine Simpson is published by 4th Estate today at £14.99.

Catherine will discuss her book at Lighthouse, Edinburgh’s Radical Bookshop, on Wednesday 20 February at 7:30pm, see www.eventbrite.co.uk for tickets.