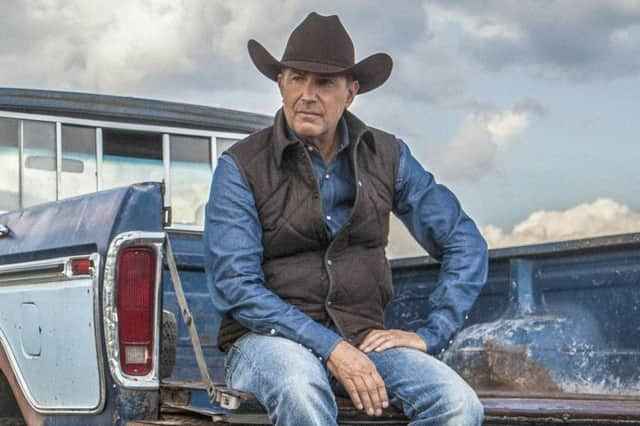

Kevin Costner back in the saddle with modern-day western

Few actors seem more to the saddle born than Kevin Costner. On screen, he’s ridden the American frontier in Silverado, Open Range, Wyatt Earp and his Oscar-winning calling card, Dances With Wolves. Off screen, he owns a 160-acre ranch in Aspen, Colorado, and fronts a band called Modern West. Which makes him a perfect fit for Yellowstone, a modern-day western created by Taylor Sheridan (Wind River, Hell or High Water) with a protagonist and storyline cut from 150-year-old cloth. Costner plays John Dutton, the patriarch of the largest contiguous cattle ranch in the United States – the size of Rhode Island, best navigated by helicopter – which abuts a national park, an Indian reservation and a town overflowing with land developers and energy speculators.

It’s a violence-tinged saga, and everyone wants a piece of Dutton’s Montana empire, including the daughter and three sons under his care since his wife died. Yellowstone, which debuts tomorrow is the first dramatic series on Paramount Network (the rebranded Spike TV). It was filmed, in part, at the historic Chief Joseph Ranch in Montana’s picturesque Bitterroot Valley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He’s over the edge, he absolutely is, but he’s real clear on why he’s doing things, and his fingerprints are on a lot,” Costner says. “The only morality that exists is the one right in front of him in how he protects his family, his ranch and the people that work on that.”

In a phone interview from his spread in Santa Barbara, California, with its baseball field and Pacific view, Costner, 63 and good-naturedly laconic, ponders the allure of the western, Manifest Destiny and plans for his second act.

Here are edited excerpts from the conversation.

I grew up on a ranch so I know a little about this world. But we sure don’t use a helicopter to count cattle.

That’s a cowboy term for you know a lot – “I know a little bit.” If somebody says, “Can you play baseball?” I say, “I can play a little.” It’s code for, “Yeah, I know.”

So you know baseball. But do you know ranching?

It’s a time-honoured thing, people making a living on horseback moving cattle. But in terms of how that trade is plied today, the world that Taylor was drawing was something very new to me. It’s like going to see Cirque du Soleil versus the old circus. There’s still the clowns, the jugglers, the almost freakish things. It’s held onto its carnival roots. They just reinvented it.

John Dutton can be as fearsome as an old-fashioned Old West land baron.

He’s a modern-day CEO, if you will, probably more than any of the generations before him, simply because he’s had to arbitrate so many problems with lawyers and encroachment and white-collar people coming after his land. The urbanisation and environmental protection that are threatening his ranch are much different than (what faced) his predecessors, where they basically took the land and were stubborn enough, maybe vicious enough, to hold onto it. Characters that took up legendary status in the West were very capable of making really hard decisions that were probably questioned by people – but not for very long.

What’s the appeal of the western?

Most westerns, I just don’t like them. But there (are) six or seven that really marked me because they somehow got under the skin. You didn’t know the type of individuals you were running into on the trail, if they’re in need of water, in need of food, a psychopath. When those situations are drawn carefully – and most of the time they’re not, because people got used to the idea of black hat, white hat, a bad guy for a good guy to knock down – a real dilemma sets itself up for very heightened drama. I think westerns are working their very best when we see a certain incident and go, “God, I wonder if I would have made it.”

Do you recall when you fell in love with the West?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen I was seven, I saw How the West Was Won at the Cinerama Dome (in Hollywood) and one of the first images – coming across this lake that didn’t have a ripple in it, like glass – was Jimmy Stewart in a birch-bark canoe. And I knew who I was at that moment. When he pulled that canoe up onto a beach, there was this group of exotic-looking people, and I thought: “I’m interested in who they are. I’d like to live in a world where they are.” I actually went out and built three canoes between that age and about 18 simply because I wanted to go down the rivers that Lewis and Clark went. I wanted to explore this America when it was like the Garden of Eden.

Back to baseball: Bull Durham joins the Criterion Collection next month.

I’m really happy to hear that. Ron Shelton and I did Tin Cup and Bull Durham together, and we’re talking about doing something that completes the trilogy of that idea. It’s all linked but not the same movie, but just like John Ford’s trilogy of Fort Apache, (She Wore a) Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande weren’t the same movie. For Ron and me to circle back to each other and create an adult romantic comedy set against the zaniness of sports, it will be interesting if we’re able to do it.

You’ll juggle moviemaking with making a series?

Yeah, it’s important to make sure that there’s time for my own projects, that they represent a different type of storytelling. I have a western I’ve been wanting to do for a long time. It’s a 30-year span, and it debunks the theory about how towns came to be. It’s a powerful piece and something I’d like to bring to the big screen as I play out the second half of my career.

What do you mean by “how towns came to be?”

The story of America just repeated itself from sea to shining sea. There were the Native Americans everywhere, and we ingratiated ourselves the best we could. And then, when there were enough of us, we killed them. And as America expanded, we kept repeating these promises that we’re just passing through, that we’ll share the land, and none of it was true. I’m just kind of sad that we don’t teach that very much in our country.

When did the second half of your career begin?

Well, it probably began a long time ago but I’m acting like it just began now. (Laughs) I want to know what I’m doing, when I’m going to do it. I want to find true partners and make these films and find distribution that makes sense to the theatres. I want to control my own destiny.

© NYT 2018

Yellowstone begins on Paramount Network tomorrow, 9pm