Insight: Father of freedom turned tyrant '“ life under Robert Mugabe

“I first met Robert Mugabe when he was living in exile in Maputo. The occasion was a UN apartheid conference in Nigeria in 1977, but in 1979 I met him in Mozambique for a much longer conversation. He willingly talked to me because he knew that I had been declared a prohibited immigrant to Rhodesia by the illegal Smith regime after being arrested at the airport in 1972. He was regarded as a Marxist both by the Rhodesians and the British government, the latter of whom regularly hoped for some Nkomo/Muzorewa government to succeed Smith.

“He was quietly spoken but suspicious that the UK government favoured the Muzorewa internal settlement and said he would only attend a constitutional conference if transfer to genuine democracy were guaranteed. At the end of our meeting he gave me an interview recorded on my assistant’s tape recorder which was used by the BBC.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In Salisbury where I met Bishop Muzorewa, who had lifted my PI status, I had talked with General Walls, commander in chief of the Rhodesian forces and a number of African political figures. I also visited my ex-Borders constituent farmer Jack Kay with whom I had kept up a dialogue over the years (he later became a junior minister in Mugabe’s government). He like most whites assumed Muzorewa would win any election and he suggested I talked without him to Muzorewa’s local chairman who worked in his kitchen. I asked the man who would win the election and he replied ‘Mr Mugabe’ thus confirming the impression I had already gathered as the general African view.

“When I got back to Britain I wrote a memo to James Callaghan as prime minister with a copy to Francis Pym as opposition shadow foreign secretary. I gave them my findings and recommended the appointment of someone of political weight to take things forward. This was later done by the incoming Conservative government in the shape of Christopher Soames. Pym had struggled to keep the party’s far right at bay, and Peter Carrington records in his memoirs that Margaret Thatcher’s instincts “were in line with those of the right wing”. Nevertheless Carrington successfully steered the Lancaster House conference to an acceptable conclusion.

“Mugabe was elected as prime minister and I accompanied Prince Charles and Carrington for the independence celebrations, memorably at a dinner in government house presided over by Christopher and Mary Soames, with Robert and Sally Mugabe and Nkomo and Muzorewa all present. Sally became a leading and constructive public figure in her own right. In the days we were there I had a meeting with David Smith who had been Ian Smith’s finance minister and whom Mugabe had sensibly kept on. He leaned forward on his desk and said ‘You and I had many disagreements over the years but I have to tell you that having served under four prime ministers in this country Mr Mugabe is not only the most able but also the most courteous’.

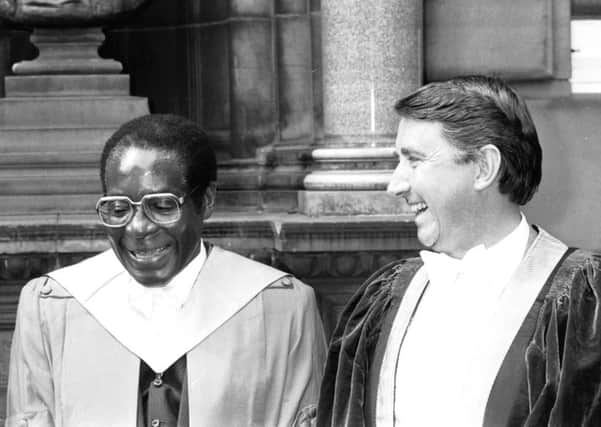

“In 1986 I was back chatting to Mugabe on his sofa (a photograph appears in my autobiography) when he jokingly asked how my ‘Patriotic Front’ was going compared to his, and we agreed that David Owen was easier than Nkomo. Around that time he was given lunch by Thatcher in Number 10, when I was one of her guests being received by them both at the entrance to the dining room. Patronisingly she said, ‘Prime minister, do you know the leader of our Liberal Party?’ Mugabe simply embraced me and said ‘Hello David’.

“Her face was a picture and I knew it was the only time I ever got the upper hand with her.

“But after the sad death of his wife Sally he married Grace who had been a typist in his office. I found myself again in Salisbury trying to get to a front-line conference in Namibia, and hearing that Mugabe was going to be there I phoned and asked if I could get a lift in his plane. He did not have a presidential plane, simply commandeering one from Air Zimbabwe whenever he wanted. I boarded the back of the plane and watched the arrival of the president and his wife with full military honours on the tarmac.

“After we took off I was summoned to join him in the front and thought this would be a good opportunity for a serious conversation before the conference. The seats on one side of the first-class cabin had been removed, while he and Grace sat in two red thrones facing each other. I sat in an ordinary seat across the aisle from him.

“Then he asked for their baby to be brought in and sat dandling it on his knee for the short flight. No sensible talk took place, and that was the last time I saw him, because he fell more and more under the spell of Gucci Grace as he descended into old age.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

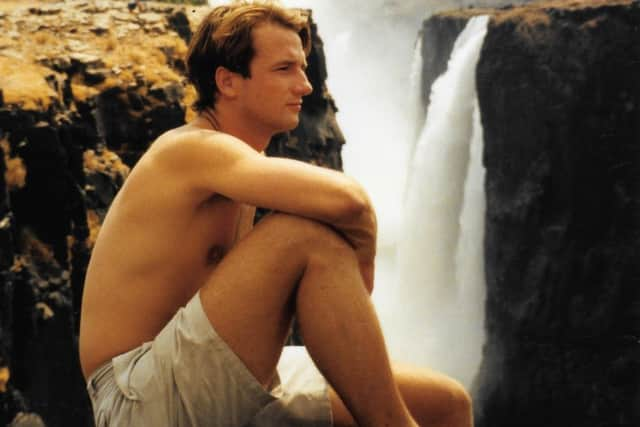

Hide AdGraeme McKinnell, 48, originally from Edinburgh, lived in Harare as a graduate architect for five years from 1995 to 2000, where he was recruited to work on a design for Harare International Airport.

“I was a student at Dundee University and one of my lecturers had a connection with a firm which was looking for graduates to work with them on a competition for the design of Harare Airport and I got the job. It was a three-year contract and I thought I’d give it a year – then had such a good time, I ended up there for nearly six. Although unfortunately, we lost the airport design competition as Mugabe awarded the contract to a company his nephew was involved with.

“It was in 2000, around the 20th anniversary of Zimbabwean independence, when it all started to go sour for Mugabe. He was forced to keep all of the promises he had made 20 years earlier, which included giving the land back to the landless – and the land redistribution programme kicked off. Before that, things had been pretty good for 20 years and when I went there in 1995, it was the peak of it being such a good place to live and work as a young expat.

“We had a great life. It was still a Third World country, but that was part of the excitement. There was a background of corruption and some employment issues, but there was no animosity between blacks and whites and it was a vibrant and good place to be.

“There was a bit of a bump in 1997, when inflation started to rise, prices shot up very rapidly at one time and there were a few riots – but it didn’t compare to the inflation that happened from 2002 to 2008.

“Then there began to be an undercurrent that things were starting to go wrong. There were roadblocks around town and people started making plans to go elsewhere. Inflation got worse and worse. Although I was an expat, I was employed as a local and while I was still earning a decent salary to live there, the devaluation against the pound was huge and it translated to mere buttons in UK currency and I realised it was doing my future no good to stay.

“Everyone who could was trying to leave, it was so sad. I have kept in touch with a lot of people from there and there’s still a few in Zimbabwe, but most left. I visited a year later to attend a friend’s wedding – the only time I have been back to Zimbabwe – and I noticed a change. There was a bit of intimidation because of everything that was happening with the white farmers. I didn’t feel comfortable any more, which enforced my feeling that my decision to leave was the right one. If the land redistribution hadn’t happened, if Mugabe hadn’t done that and if the economic situation was different, I probably would have stayed. My residency came through just after I left, but to keep it up, I would have to spend a number of weeks a year in Zimbabwe and I just couldn’t see that happening, so I gave it up.

“Maybe Mugabe stepping down will help people start thinking about going back. There’s a sense of relief and optimism among my Zimbabwean friends, but what transpires we can only wait and see.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaggie Chapman, 38, is co-convenor of the Scottish Green Party and rector of Aberdeen University. Originally South African, her family had moved to what was then Rhodesia in 1978 for her father to take up the post of director at the college of music in Salisbury, now Harare. She was born a year later in what was, for that six-month period, known as Zimbabwe Rhodesia. Zimbabwe was granted independence when she was a baby. She moved to Scotland, initially to study, in 1998 and has lived here ever since.

“My mum lives in the house I was born in Zimbabwe, so I still have strong ties there. They moved to Zimbabwe for my father’s job before I was born, when there was still a war going on.

“We had a very happy childhood. We went to a school where the education was entirely mixed and white students were a minority. Looking back at my A-level class of 65 people, there were ten white students, but it wasn’t something we really noticed or thought about. There wasn’t any kind of apartheid like there was in South Africa at the time. I was aware as a child of inequality, but it was more structural or class based rather than racial.

Mugabe, for all his faults, saw education as a priority, at least in the first decade after Zimbabwe became independent and my sister and I benefited from that. To this day, Zimbabwe still has high literacy rates. That came from across the political spectrum, that as a post-colonial state, if a country was going to make a success of itself, it needed to be educated.

“As a child, I never felt deprived of anything. There were things which were just part of day-to-day life, such as that the school we went to, which was near my dad’s work, was chosen because there was a petrol shortage, so he could drop us off on the way and not waste fuel.

“There is no question that land redistribution was necessary, but the way in which it happened not only reduced the production of the farms, but left farm workers without jobs and without communities as some of the large farms had schools and clinics and suddenly they were gone.

“I moved to Scotland to study in 1998 and economically, Zimbabwe had started to decline. Over that period, I saw it change a lot. When I left, a pound was worth about $27 to $30. Zimbabwean dollars, then within a few years they were just a laughing stock. They printed trillion dollar notes. There was an economic structural adjustment imposed on us by the IMF and the World Bank which was lauded as the thing that would open Zimbabwe’s economy to the world, but it contributed clearly to the economic downfall.

“My mum and dad lost all of their savings overnight. They were left with just a dollar in their bank account.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Even now, if you go to Zimbabwe, there is no proper currency, just Zimbabwean bond notes, which are technically worth the same as a US dollar, but do not have anything behind them. Some shops take US dollars, some take Botswanan currency or Mozambique.

“There was nothing in the shops. At first, when there were empty shelves, they filled them with toilet roll. Just aisles and aisles of toilet roll. Then they couldn’t even get that and the shelves were empty.

“People actually died of starvation and I think that is something that a lot of people don’t realise. It devastated many people’s lives.

“People started growing things locally. People even started growing maize on the grassy bits next to pavements in Harare, just to survive.

“Mugabe was the father who led Zimbabwe to its freedom so he was given a lot of leeway and I don’t think that same leeway will apply to the second president. I believe transparent processes will be built up around him so that he doesn’t turn into another Mugabe.”

Xzike Zolani, 29, was born in the Zimbabwean capital, Harare, but moved around as a child, living in Morningside, Edinburgh for three years from 1993 while his father, a doctor, worked at the Royal Infirmary. The family returned to Zimbabwe in 1996, when Zolani was 10 years old.

“We lived back in Zimbabwe for a few years from when I was ten, but when I was about 14, the start of the downfall began. There was huge inflation and our currency was devalued, so we left. I married an English girl and we have lived together in Zimbabwe for the past three years as I saw there were a lot of opportunities there. However, when the coup began, her parents began to get worried and we made the decision that we would return to the UK. She is now living in Manchester, while I fly back and forward between Zimbabwe – where I still have business interests – and the UK, for now.

“A lot of Zimbabweans are really scattered around the world. The word ‘family’ is a very different thing to say for Zimbabweans. I have travelled around so much that I could live anywhere and I just want to be wherever my wife is - but wherever I am, I still always connect with Zimbabwe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When my wife first came here, she was gobsmacked when the power just went off. She asked me when it would go back on and was shocked when I said it might be a couple of days. It is quite normal for me. You might have no power cuts one month and 100 power cuts the next. The internet is not reliable, it is very difficult to do business.

“Sometimes they decide that certain products cannot be imported and you cannot get things you need. However, there are business opportunities. If you build something in Zimbabwe, you don’t really have much competition. There has been a feeling as Mugabe has got older that the young people will come back and bring with them what they have learned in the West.

“This is the first time in 37 years that there has been a change. In my whole lifetime, I have only ever known one president. However, the older generation knows about what the new president has done in the past. We really need elections.

“The average Zimbabwean wants to come home. There will be some who have settled abroad, but most will dream of coming back to Zimbabwe.”

Simon Jones, 33, was born in the UK to Zimbabwean parents and was brought up in South Africa until he was 14, when the family moved back to Bulawayo, in the south west of Zimbabwe. He took up a job in Scotland as an adult.

“My parents were never good at timing. We moved back to Zimbabwe in 1998, just before things started to get difficult. Looking back, I can see it was an interesting time to be there, but then, it was just life. My dad had fought in the Rhodesian Bush War and, while it wasn’t exactly exile, I think they had just wanted to get out of Zimbabwe for a while and have a rest, so they had moved to the UK, where I was born.

“When we went back to Zimbabwe, my dad tried to set up a tourism business, getting tourists into Zimbabwe for safaris and golf, but at that time, things were getting bad and it wasn’t a tourist destination, so it didn’t work. For a long time, he commuted to Botswana, to work in IT, setting up computer systems, but that meant he was separated from us for weeks at a time.

“We used to go into the local supermarkets and there would be empty shelves. Imagine that, going into Asda or Sainsbury’s and there being literally nothing there. My mum had a network of friends and she would hear that there was sugar one day in such and such a supermarket and go there and get some. Or we’d hear a friend had brought a crate of cooking oil up from South Africa and she’d go and get some from them. She didn’t work, but between shepherding us to school and running around trying to get all of the things we needed, it was a full-time job.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There were petrol and diesel shortages, which had a knock-on effect on everything, like food distribution. You would queue at petrol stations, sometimes for two days, then eventually a tanker would drive up and fuel would be put in the cars and when it ran out, that was it and you might not get any.

“It has taken a long time to put Zimbabwe behind me and stop looking at it as an option. When Mugabe went, my whole family was messaging each other, saying ‘Shall we all go home now? Let’s book a flight for Tuesday,’ but we’re joking. I feel very at home in Scotland, this is where I want to settle down and have kids, though we’re temporarily living in Hong Kong for a year at the moment.

“But if one of my dear old friends phoned me up tomorrow and said ‘Simon, I’ve got a job for you in Zim, you’ll live comfortably, all your old friends are here,’ I would have great difficulty saying no.”

John McKenzie, 66, lives in Dalgety Bay, Fife. He worked as an electrical engineer in southern Africa for 25 years, including on a long-term project on a power plant in northwestern Zimbabwe in the mid 1980s.

“There was a lot of bad feeling there in the 1980s, especially towards Mugabe. He wasn’t Nelson Mandela, who I have a lot of respect for. He was an absolute tyrant and the damage he caused in that country was unbelievable. It used to be known as the bread basket of Africa, it was a beautiful country. Wankie was a small coal mining town and local people I knew there who worked on the plant liked to go out fishing on the Zambezi River on their boats.

“There had been a lot of sanctions on Zimbabwe before independence, when it was Rhodesia, and even a few years afterwards, it was still hard to get things when I was there.

“If you went for a pint, you were often served it in an old jam jar, they didn’t have proper glasses. You couldn’t get parts for cars, people struggled to find tyres and things.

“My dad’s oldest brother and his wife lived in Salisbury [now Harare], but moved to Perth, Australia, in the 1980s because they just couldn’t stand living under Mugabe.”