Embryo study brings hope of improving IVF success rates

Only one in four IVF attempts are successful and an embryo failing to implant in the womb is a major cause of early pregnancy loss.

For the first time, scientists have been able to maintain living embryos outside of the body for 13 days after fertilisation, allowing them to study key stages of development.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEmbryo research can be controversial and UK law only allows embryos to be studied in a lab for up to 14 days, which is the point when neurons begin to develop in the brain.

Independent advisers at the Nuffield Council on Bioethics will review its position on the timeline later this year.

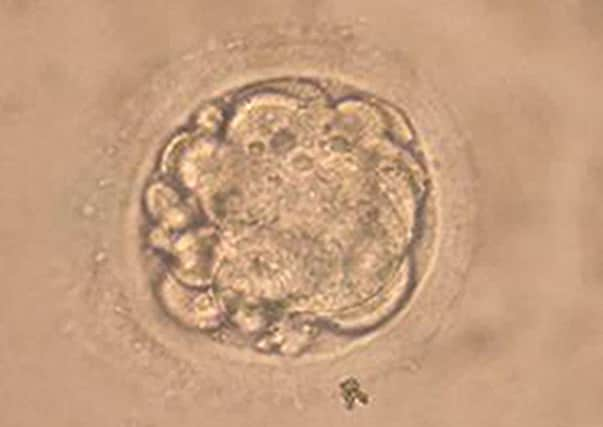

This study, published in Nature and Nature Cell Biology journals, is the first time scientists have been able to keep the embryo alive outside the body for more than seven days to see how small balls of stem cells, known as blastocysts, develop.

Lead author Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, from Cambridge University, said: “Implantation is a milestone in human development as it is from this stage onwards that the embryo really begins to take shape. It is also the stage of pregnancy at which many developmental defects can become acquired. But until now, it has been impossible to study this in human embryos.

“This new technique is a unique opportunity to get a deeper understanding of our own development during these crucial stages and help us understand what happens, for example, during miscarriage.”

Leading fertility expert Professor Allan Pacey, from Sheffield University, said: “These are two very elegant papers which have the potential to revolutionise our understanding of the early events of human embryo development and, in time, some of the reasons behind aspects of disease and disability.”

He acknowledged there was opposition to experimenting on embryos but said it did not open a door to couples “growing babies in the laboratory”.

Dr Callum MacKellar, from the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics, said: “What they are doing doesn’t present new ethical issues as long as they remain within the 14-day limit. There is a slippery slope once you start trying to extend that window.”