Dreams of Glasgow: an Eritrean refugee's story

In a rare and bitingly bitter Roman winter braced for a snowstorm brought by the beast of the East, an Eritrean boy Sonny Tesfaye*, 15, had been swept in as if from another wilder, warmer world that had taken his boyhood and dumped him dazed in a foreign land.

Just 12 years of age when he left home, it had taken Sonny Tesfaye*, three years to get to Europe from Eritrea and cost his father a total of $3,800 - for the first leg to Sudan $1,600 and then $2,200 to get to Italy from Libya. He was in a prison there - tied up on most days along with 300 other girls and boys – and stayed for a year while his father got the money together to pay smugglers to take him on one of the most dangerous migratory crossings in the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSonny had only been in Rome three days and despite severe weather warnings he and his friends were fixated with one thing - to keep going. They had survived the Sahara, prison in Libya, and the treacherous Mediterranean, snow was not going to hold them back from reaching family in other parts of Europe.

The boys said they wanted to get an education in Europe with extended family and not grow up to be soldiers in Eritrea. They had been hanging out around Roma Tirbutina station where UNICEF/Intersos mobile unit had spotted them during their outreach visits and told them they could go and stay at the 24 hour centre where they would get help, a warm bed, good food, and care.

They’re among the 17,000-odd children who’ve arrived in Italy in the past year and 93 per cent of them, like Sonny, travelled alone. About a third of them take off on their own and go ‘under the radar’, or unaccounted for. There’s an underworld, often in train stations, that is helpful for them – a network from home for refugee and migrant children that connects them with family and communities. And then there is one that is harmful – traffickers who are never far away, waiting to prey on children, on the most vulnerable, exchanging help and information for services, cheap labour; all too often boys and girls get caught up in prostitution and drug rings.

We meet again the next day at the Intersos 24 hour centre. It’s far out of town, in a newly renovated building, once a school. It’s bright, cheerful and warm – the boys are playing table football games, there’s a pizza-making class underway in the open kitchen, others are watching Eritrean films on the computers, some of the girls are asking for more fashionable clothes – one of them didn’t like the 70-flared jeans they had been given. But I told her vintage is big in Europe now and she would be super fashionable. She took another look in the mirror through new eyes and partly persuaded, she put them on.

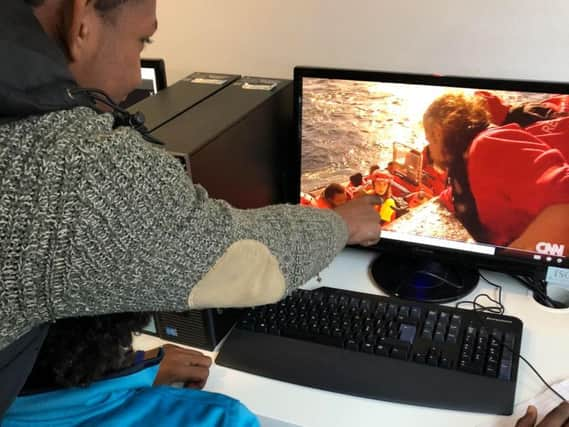

Sonny goes on to the internet to check his Facebook – that’s how he and tens of thousands like him – navigate their way to a form of freedom. He’s the oldest of his family and a bright, streetwise boy, quick as a whip to pick up new tricks. I show him a story on CNN that I had been involved with and astonishingly he and his friend recognize one of the women who helped rescue him in the Mediterranean just a month back.

After more than two years working on the migration response in Europe, I have seen the ugly underbelly laid bare in this continent’s beautiful old cities, like Berlin, like Rome, Athens, tourist spots on the Greek islands like Lesvos.

I visited what can only be called a slum, where some 100 people live – to call it live would be a lie – in the rotting carcass of an abandoned factory. Some weeks before UNICEF/Intersos mobile unit had rescued 40 children – unaccompanied migrant children and some with parents, and referred them to the social services. It was hard to believe it was Europe.

Migration has become a lightning rod for European values and obligations to international treaties like the Refugee Convention of 1951 or the Convention of the Rights of the Child and even to EU asylum policies. It has split nations and brought out the worst - more than 5,000 attacks on migrants in Germany alone in 2016/2017; Africans being spat at on the streets; even the UNICEF/ Intersos mobile unit had been attacked by right wingers who punctured the tyres. It has though also brought out the best in Europeans, like those opening their hearts and homes to the strangers in their midst. It has challenged the UN to work in high income countries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are no easy answers for children uprooted and on the move like Sonny. The Italian law is on his side, if not always the people. As the oldest of his family Sonny is under pressure to ‘pay back’ to his people that means getting an education, getting a job – he wants to be an engineer – and that means finding his way to his uncle in Glasgow and getting on with things there. Easier said than done. I show him on a map that there are a number of countries and another stretch of water, the English Channel that lies between him and his uncle in Scotland.

Officially, under EU Dublin Rules states must offer protection to a person at risk, like Sonny. Greece and Italy are the on the frontlines where children must seek asylum but few want to stay. In theory if there is a family connection in another member state, they then can apply to be relocated. But that’s on paper. In reality, time is the enemy of these children. They don’t trust the system in Europe to recognise them as children, as teenagers, not trouble, as children who seek the home and care of an uncle, a cousin, in the same way as Europeans would track down their fathers and mothers if separated.

They see a system that punishes them, that makes it so tough as to be a warning to others not to dare follow. In effect that is what pushes them into an underworld without papers, into the hands of profiteers of misery. That and the lies that smugglers lure them with on social media about crossing the Mediterranean on fancy yachts, about great schools and good jobs that await them.

And so some days later I inquire again about Sonny and phone his uncle in Glasgow. Sonny took nothing with him except the clothes on his back, but he remembered everything, phone numbers, addresses, Facebook passwords. Lost in translation, I didn’t manage to establish on the phone with his uncle if he and Sonny had made contact, but I gave him a number to try someone who could speak some Tigrayan.

But then I found out from the UNICEF/ Intersos contacts that Sonny and his two young compatriots had taken matters into their own hands and were on their way to Ventimiglia on the border with France. They had all been given a bracelet and a booklet ‘Young Pass’ (pictured) with some basic information on his rights and warned them of the risks. But things like outreach services and care centres can only ever be a temporary band aid until there are proper safe, legal and lasting measures in place.

For now great dangers lie ahead for Sonny as he continues on his improbable mission overland to Scotland. If he had had a humanitarian visa, or been relocated under family reunification rules, if he could have taken a flight from Asmara to Glasgow, it would have taken just two days or so and cost about $300. Instead it has taken three years – and he’s not there yet – it cost not only $3,800 from his father to smugglers, but it has cost something all the money in the world can’t buy, his boyhood. And he’s not there yet.

On the next step of his already arduous short life in pursuit of another life, another beginning, the hardest part may still lie ahead.

*Sonny's name has been changed.

Words by Sarah Crowe: UNICEF senior communications advisor based in Geneva.