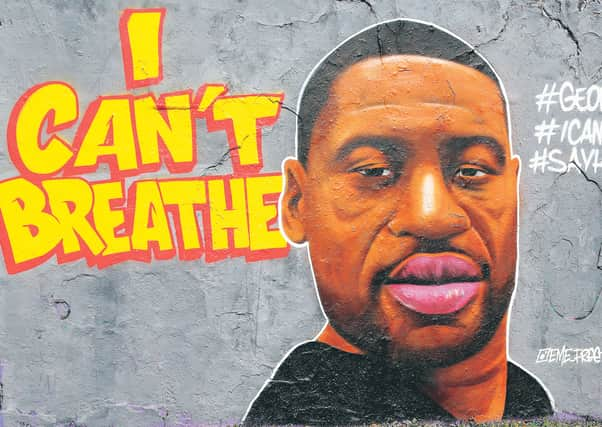

Claire Heuchan: ‘Here too Black men die in the custody of white officers’

But that doesn’t make it any less traumatic to watch. I can’t stop thinking about George Floyd’s final moments, how lonely he must have felt. George didn’t get to die in his bed at a ripe old age, surrounded by children and grandchildren. He didn’t even get to see his little daughter grow up. George Floyd was killed in the prime of his life. All of the tomorrows stretching out in front of him were crushed into nothing by the knee of a police officer. And the minutes leading up to his death became a viral video.

The awful truth is that sharing these videos, making them public, is often the only way to hold a white police officer accountable for ending a Black life. George Floyd’s death was the spark that lit protests across all 50 of the United States, and cities across Britain. This level of mass grief and fury is impossible to ignore. All four officers involved in his death now face criminal charges. But public consciousness is ablaze because countless other Black men, women, and children have been the victims of police brutality too.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is state-sanctioned violence. Not an anomaly, but the natural product of a society that was quite literally built by the slave trade. American police brutality can be traced back to the slave patrols of the 1700s. White vigilantes tracked down enslaved Black people who had escaped lives of backbreaking labour, torture, and sexual violence. And American racism has British roots. Anti-Blackness was exported from this island to the American colonies.

Britain’s own history is full of racist violence: imperial expansion, the colonisation of lands and natural resources, the transatlantic slave trade. And the anti-Blackness found in modern day Britain is part of that legacy. Black people are twice as likely to be fined for breaking lockdown than white people doing the same. Black people are 40 times more likely to be targeted through stop and search measures. Black women are five times more likely to die of complications in pregnancy and childbirth than white women – our Black maternal mortality rate is higher than America’s. And Black British people are even more overrepresented in the prison population than African Americans. Here too Black men lose their lives in the custody of white police officers. In Kirkcaldy, during 2015, a man named Sheku Bayoh died in circumstances with similarities to George Floyd. Up to nine police officers used batons, CS spray, and pepper spray against him. He suffered 23 injuries. Medical evidence suggests he died of positional asphyxia, meaning he could not breathe.

Collette Bell, his partner, said: “George Floyd was kneeled upon until he took his last breath. So was Sheku, only more weight and more officers kneeled upon him. George Floyd stated, ‘I can’t breathe.’ So did Sheku. It was police brutality and racism and it happened in Scotland.” To the family’s distress, no police officers are being prosecuted, but a judge-led public inquiry is to be held into his death.

In response to protests in Edinburgh and Glasgow, Nicola Sturgeon has said she feels “total solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement”. While well intentioned, the First Minister’s words don’t carry much weight. She’s the premier politician within a parliament that, in the space of 21 years, has not seen the election of a single Black MSP. Nor has any woman of colour from any ethnic background ever been elected to Holyrood.

This failure is not Sturgeon’s alone. It belongs to every political party. And the time for action is long overdue. During the 1997 general election, Labour greatly improved female representation at Westminster with all-women shortlists in half of all winnable seats. Parties at Holyrood should create all-Black and all-women-of-colour shortlists. In a healthy democracy, no segment of the population can be denied political representation.

Exclusions from governance have consequences. They shape how policy is made, and whom our laws actually serve. With nobody to speak from experience on the issues facing Scotland’s Black population, how can Holyrood claim to represent us? Over the course of five election cycles Holyrood has had a total of four Asian MSPs. Today, out of 129 MSPs, only two aren’t white: the SNP’s Humza Yousaf, who is Cabinet Secretary for Justice, and Labour’s Anas Sarwar. Both men have been on the receiving end of horrific racist abuse since taking office. Mr Yousaf – the first Holyrood Minister of colour – has been left in fear for his life after online threats. He now carries a personal alarm.

This abuse isn’t random. It’s not just trolling. It’s a very deliberate attempt to push people of colour out of public life. Though we are underrepresented at every level of Scottish politics, what little gains we have made are fiercely contested. I worry that a generation of Black and Brown kids in Scotland will see this racist backlash and decide a career in politics is not for them. And the cycle of under-representation continues. These exclusions don’t just exist on the frontline of Scottish politics. They happen behind the scenes too.

Leslie Evans, Scotland’s Permanent Secretary, tweeted a picture of herself taking the knee “in support of #BlackLivesMatter”. This is all good and well. But only 1.8 per cent of civil servants in Scotland are people of colour. There are only 10 ethnic minority civil servants at the top level. These figures haven’t been broken down by race, but I suspect few if any of those civil servants are Black. I’m more interested in what – if anything – Evans is going to do to improve race representation in the civil service than the contents of her social media account. Performative gestures of allyship help nobody.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeaningful change doesn’t happen overnight. But I wonder how it can happen at all when Black people are treated as a negligible part of the Scottish population. We can take to the streets and protest as part of the international Black Lives Matter movement. We can document our own histories, as the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights have done. We can form our own creative communities, like the amazing Yon Afro Collective. But who in parliament is going to listen to what we say? Who is going to hear our words from a place of personal understanding? Which of our 129 non-Black MSPs will advance Black rights in the parliament? Nothing about us can happen without us.