Book preview: The Girl On The Ferryboat

Today, we produce an extract in English and Gaelic from award-winning poet and author Angus Peter Campbell’s new book, which will be published in both languages on Monday.

It was a long hot summer: one of those which stays in the memory forever. I can still hear the hum of the bees, and the call of the rock pigeons far away, and then I heard them coming down from the hill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough it wasn’t quite like that either, for first I heard the squeaking and creaking in the distance, as if the dry earth itself was yawning before cracking. Don’t you remember – how the thin fissures would appear in the old peat bogs towards the middle of spring?

At the time, I myself was very young, though I didn’t know it then. The university behind me and the world before me, though I had no notion what to do with it. I had forever, with the daylight pouring out on every side from dawn till dusk, every day without end, without beginning.

I saw her first on the ferryboat as we sailed up through the Sound of Mull. Dark curly hair and freckles and a smile as bonny as the machair. Her eyes were blue: we looked at each other as she climbed and I descended the stairs between the deck and the restaurant. ‘Sorry,’ I said to her, trying to stand to one side, and she smiled and said, ‘O, don’t worry – I’ll get by.’

I wanted to touch her arm as she passed, but I stayed my hand and she left. My sense is that she disembarked at Tobermory, though it could have been at Tiree or Coll. For in those days the boat called at all these different places which have now melted into one. Did the boat tie up alongside the quay, or was that the time they used a small fender with the travellers ascending or descending on iron ropes?

Maybe that was another pier somewhere else, some other time...

The girl on the ferryboat was called Helen: she’d been visiting friends in Edinburgh and when she turned round, the violin was gone forever.

Waverley Station.

She’d only put it down on the bench for a moment as she searched for her purse, and when she looked back it had disappeared.

No one in the world noticed, for it continued as before. It was 8.20am, the very middle of the rush hour. Everyone ran. No one carried a violin under their arm. A terrible piper busked over by Platform 17, where the train from Euston was due. An old man, still drunk from the night before, lay slumped on the bench. She wanted to shake him awake, but of course he wouldn’t know.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt had been in the family for generations, brought back from Naples by her great-grandfather on her mother’s side sometime in the 1880s. Though it was no Stradivarius, it made a beautiful sound: deep and mellow, yet bright and tuneful.

‘An angel made it’, the old people used to say and began to compare it to the famous chanter played by the MacKinnon family, which had been made by the fairies in Dunvegan. Nobody but a MacKinnon could play that chanter, and whenever anyone else touched it, it lost all its music.

She herself was twelve when she was given the fiddle by her mother. After Archibald died it was played for a while by his youngest son, Fearchar, but when he died with the millions of others in the trenches, the fiddle fell silent for two generations. Helen’s mother found it one day in the loft of the byre beneath a pile of old straw and had it restored.

‘Not to worry,’ her mother said when she phoned to tell her the news. ‘It’s an impossible thing to lose. It may have gone out of our sight, but his eye will still be upon it.’

This omnipotent eye was her grandfather’s, which still kept a close watch on the fiddle from beyond the grave.

‘It will burn in the thief’s hands,’ she said. ‘The instrument will refuse to play.’

This faith was not an unreasonable thing. Had not everything that had ever been stolen ultimately not turned into ashes? Was it just some kind of strange coincidence that her own sister’s husband had died no sooner than he remarried? And what about that time the minister’s motorcycle was stolen from outside the manse, only for them to find the bike and rider at the bottom of the ravine the following Sunday?

She was on her way home now to deal with it all. Not the loss of the instrument, of course, but the grief and the story which lay behind all of that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdB’ E SAMHRADH fada teth a bh’ ann: an seòrsa a dh’fhuiricheas anns a’ chuimhne gu bràth. Cluinnidh mi fhathast dranndan nan seillean, ’s ceòl nan calman-creige fad às, ’s an uair sin chuala mi iad a’ tighinn a-nuas on bheinn.

Ged nach robh e buileach mar sin a bharrachd, oir an toiseach chuala mi an gìosgan ’s an gnùsgain aig astar, mar gun robh an talamh tioram fhèin a’ mèaranaich ’s a’ sgàineadh. Nach eil cuimhn’ agad – mar a nochdadh na tuiltean tana sa mhòintich a-null mu mheadhan an Earraich?

Aig an àm, bha mi fhèin gu math òg, ged nach robh fhios a’m air an sin an uair sin. An oilthigh air mo chùl ’s an saoghal romham, ged nach robh for agam dè dhèanainn leis. Nach robh gu sìorraidh agam, le solas an latha a’ dòrtadh timcheall orm air gach taobh o mhoch gu dubh, gach latha gun chrìoch, gun cheann, gun deireadh?

Chunnaic mi an toiseach i air an aiseag fhad ’s a bha sinn a’ seòladh suas tron Chaolas Mhuileach. Falt camagach dorcha agus breacan-siantan agus gàire a sgàineadh na speuran. Chaidh mi fodha ann an tobar a sùilean: choimhead sinn air a chèile nuair a bha ise a’ dìreadh agus mise a’ teàrnadh na staidhre eadar an deice agus an seòmar-bidhe. ‘Duilich,’ thuirt mi rithe, a’ feuchainn ri seasamh gu aon taobh, ’s rinn i ’n gàire ’s thuirt i, ‘O, na gabh dragh – gheibh mi seachad.’

Bha mi airson a gàirdein a shuathadh fhad ’s a bha i dol seachad, ach chùm mi mo làmh agus dh’fhalbh i. Saoilidh mi gun tàinig i far a’ bhàta ann an Tobar Mhoire, ged a dh’fhaodadh e bhith gur ann an Tiriodh neo an Colla bha e. Oir aig an àm sin bhiodh am bàta a’ tadhal anns gach àite sin, a tha nis nan aon. An do cheangail am bàta suas taobh a’ chidhe, neo am b’ e siud an t-àm nuair bhiodh na sgothan beaga a’ tighinn a-mach gu cliathaich a’ bhàta, ’s an luchd-siubhail an uair sin a’ dìreadh ’s a’ teàrnadh a-mach ’s a-steach air dorsan beaga?

’S dòcha gum b’ e cidhe eile a bha sin an àiteigin eile, uaireigin eile.

B’ e Eilidh an t-ainm a bh’ air an nighinn air an aiseag: nuair a thionndaidh i mun cuairt, bha an fhidheall air a dhol à sealladh.

Stèisean Waverley.

Cha robh i ach air a cur sìos air a’ bheinge airson diogan fhad ’s a bha i coimhead san sporan, ’s nuair a sheall i air ais cha robh sgeul oirre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCha tug duine san t-saoghal an aire, oir chùm e dol mar a bha e a-riamh. Bha i 8.20 a.m. Àm na cabhaig. A h-uile duine nan ruith. Cha robh fidheall fo achlais dhuine sam bith. Bha pìobaire sgreataidh a’ bìogail thall mu Phlatform 17, far an robh dùil ri trèana Euston mionaid sam bith. Bha seann bhodach, ’s e fhathast air a dhalladh on oidhche roimhe, na laighe na chlod air beinge. Bha i ’g iarraidh a chrathadh, ach cha bhiodh fhios aige dè an saoghal san robh e.

Bha an fhidheall air a bhith san teaghlach airson ginealaichean, air a toirt dhachaigh o Naples le a sìth-seanair taobh a màthar uaireigin anns na 1880an. Ged nach b’ e Stradivarius a bh’ innte, bha i dèanamh fuaim àlainn – an dà chuid domhainn is mìn agus sgairteil is ceòlmhor.

‘B’ e sìthiche rinn i,’ chanadh cuid dhe na seann daoine, ’s ga coimeas ris an fheadan ainmeil a bhiodh Clann MhicFhionghain a’ cluich, a bha air a dhèanamh le sìthichean Dhùn Bheagain. Cha rachadh aig duine sam bith eile ach fear de Chlann MhicFhionghain am feadan ud a chluich, agus nuair a rachadh cinneach sam bith eile faisg air, shiubhaileadh an ceòl.

Bha Eilidh fhèin a dhà-dheug nuair a thug a màthair dhi an fhidheall. Nuair a dh’eug Gilleasbuig, bha i air a cluich airson greis le a mhac, Fearchar, agus nuair a bhàsaich esan còmhla le na muilleanan mòra eile anns na trainnsichean, bha an fhidheall balbh airson dà ghinealach. Lorg màthair Eilidh an fhidheall aon latha fo chnap feòir ann an lobhta na bàthcha, agus chaidh aice a h-ùrachadh.

‘Na gabh dragh mu dheidhinn,’ thuirt a màthair rithe nuair a dh’fhòn i a dh’innse na naidheachd.

‘Chaidh gealladh nach tig i air chall gu bràth. ’S dòcha gun deach i as ar sealladh, ach bidh a shùil-san oirre.’

B’ e an t-sùil uile-chumhachdach seo a seanair a bha fhathast a’ cumail sùil air an fhidhill o thaobh thall na h-uaighe. ‘Loisgidh i ann an làmhan a’ mhèirlich,’ thuirt i. ‘Cha tig port aiste.’

Cha b’ e rud mi-reusanta a bh’ anns a’ chreidimh seo. Nach do thionndaidh a h-uile rud a bha riamh air a bhith air a ghoid gu luaithre aig a’ cheann thall? Am b’ e dìreach tuiteamas a bh’ ann gun do dh’eug cèile a peathar aon uair ’s gun do phòs e a-rithist? Agus dè mu dheidhinn an turas ud a chaidh motor-baidhsagail a’ mhinisteir a ghoid o thaobh muigh a’ mhansa, ’s mar a fhuair iad am baidhsagal agus am fear a bha air, marbh aig bonn a’ ghlinne an ath Shàbaid?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBha Eilidh air a rathad dhachaigh a dhèiligeadh ris. Cha b’ e dìreach call na fìdhle, ach an dòrainn agus an sgeul a bha air cùl sin.

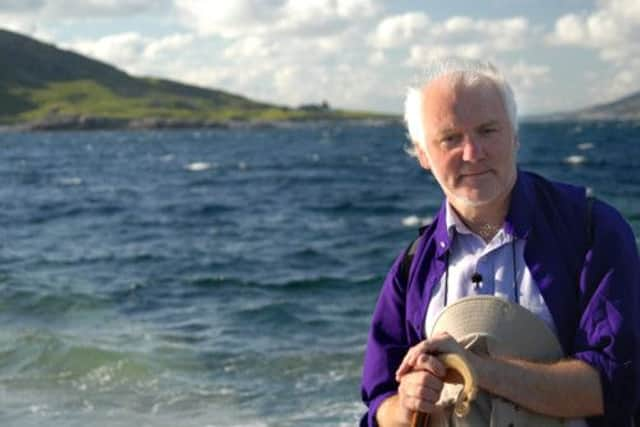

These extracts are from a new novel by Angus Peter Campbell, which is being published simultaneously in English and Gaelic on Monday by Luath Press. The book is called The Girl On The Ferryboat/An Nighean Air An Aiseag, and is also available to download now as an e-book.

Angus Peter Campbell (Aonghas Phàdraig Caimbeul) was born and brought up on the Island of South Uist. He is an award-winning poet and novelist, with his Gaelic novel An Oidhche Mus do Shèol Sinn voted into the top ten of the Best-Ever Books from Scotland in the List/Orange Awards in 2005. His poetry collection, Aibisidh, was selected as the Poetry Book of the Year in Scotland in 2012.

He works as a writer and actor and was nominated for a Scottish Bafta for the lead role in the film, Seachd. He is a double Honours graduate in politics and history from the University of Edinburgh.

Sorley MacLean reviewed his first collection of poetry as “a masterpiece”, and he has elsewhere been described as the Mark Twain of modern Gaelic literature. He lives in An Caol/Kyle of Lochalsh with his wife and children who are musicians.

The e-books for the two editions are available for download from today and the two hardback English and Gaelic language editions will be officially published on Monday.