Travel Wishlist: Greenland - Scotland on Sunday travel

I could barely see ten feet in front of me. A heavy mist hung over the tiny island of Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands), a dot in the ocean off Iceland’s south coast.

Iceland was a small part of my journey into the history of the Vikings, but an essential departure point of our voyage. Herjólfur Bárõarson was the first Norseman to settle in Vestmannaeyjar and a reconstruction of his original farmhouse (longhouse), dating back to the 9th and 10th centuries, was built here in 2006.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe’d hauled anchor the night before in Reykjavik’s old harbour, sailing south for Vestmannaeyjar on a two-week expedition on the Ocean Endeavour – an ice-class ship operated by small-group polar exploration specialists Adventure Canada.

We weren’t in Iceland long, but visited Fridheimar tomato farm, an hour’s drive from Reykjavik. Run by Knútur Rafn Ármann and family, its giant greenhouses produce delicious tomatoes using sustainable energy and the café, amid the massive vines, serves delicious homemade tomato soup and tomato beers. The farm uses only natural tap water, some of the cleanest in the world, having filtered through lava for centuries, and key to the country’s initiative to reduce the amount of plastic brought in from outside.

Iceland became a Viking kingdom around 874AD as more and more Norse people ventured north-west from the British Isles and the Faroes. The boldest Norse adventurers went on to Greenland… and so did we.

In the wake of the Vikings, we sailed west from Iceland across Denmark Strait for a day and a half towards Greenland’s seldom visited wild east coast. A millennium ago, Norse explorers in longboats sailed the same course.

At sea, our days merged with barely any darkness to separate them. Most days we breakfasted early as there was a shore excursion, with buffet lunches, and dinner served by restaurant staff. There were also presentations from guest speakers, often about places we would see on the trip.

Painting classes, local food samples and other activities tied in with the region were available too. We were joined on board by one of Greenland’s most popular singer/songwriters, Nive Nielson, and her band, the Deer Children, who performed for passengers and talked about Greenland and its captivating culture.

We entered Greenland’s waters at Kangerluluk, navigating the coastline in our Zodiacs, dodging pack ice and looking out for polar bears, seals and humpback whales. Vast glacial tongues plunged towards the water, and calving icebergs plummeted into the sea just feet away, creating small tsunamis.

Early the following morning, we arrived at Ikerasassuaq (Prince Christian Sound) – 60 miles long and only 500 metres wide in places – among the islands of the Cape Farewell Archipelago, near Greenland’s southernmost tip. Flanked by wall-to-wall ancient rock, the slow ride enabled us to soak up every inch of this impressive dog-leg gash in the land that eventually opens up into the sea and Greenland’s lush South Coast.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOur afternoon dash to shore in Zodiacs rewarded us with views to make a geologist dizzy and I climbed to the top of a hill, its sides worn by a melting glacier, leaving it smooth like a clean-shaven face.

Sailing overnight we woke off the island of Uunartoq Qeqertaq or “the very hot island”, the only place in the region where you can bathe in hot springs.

As we slid into the warm water, Nive, a Greenlander, said: “I love coming here, it’s magical.”

On the island’s far side are the remains of an Inuit village, with ten or more crumbling, traditional sod houses, unexcavated and untouched. My attention was drawn to the raised graves of the people who lived here, the remains of a skeleton in one, visible. In accordance with Inuit tradition, we introduced ourselves to the dead and explained why we were there, treating the site with the greatest respect.

We exited the fjord on to Greenland’s south-western coast, where records of human habitation stretch back over 1,500 years, arriving in the Sermersooq region with its myriad stunning mountain peaks, glaciers, and deep fjords to explore by Zodiac and on foot.

The last Norse ruins at Hvalsey hint at the story of the Viking settlements of Greenland. For four centuries Norse wayfarers managed to make a living as sheep farmers in this rugged land, building farmhouses, churches, and other trappings of European life. The best preserved Norse ruin in Greenland, Hvalsey Catholic Church, is also the location of the last written record of the Greenlandic Norse, a wedding in September 1408 when Thorstein Olafsson, an Icelander, married Sigrid Bjornsdottir, (possibly from Hvalsey). Thorstein became the king’s Lord Lieutenant in Iceland, providing a clue as to where some Greenland Norse went when the colony was abandoned.

Our last stop on the southern Greenland coast was charming and contemporary Qaqortoq, the largest town in South Greenland. With a mix of Danish and Inuit influences, it has been inhabited for 4,000 years, beginning with the Saqqaq culture and today’s colourful wooden homes reveal a distinctly Scandinavian sensibility. There are suburbs with barking dogs and racks of drying kayaks stacked by the shore.

Viking explorer Erik the Red first landed at our next port of call, the Norse site of Brattahlid, in the present-day settlement of Qassiarsuk. Erik established his farm by the beach around 985, and his descendants (including his son, Norse explorer “Lucky” Lief Ericson), lived here until the 1400s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, it’s a Unesco World Heritage Site, with a huge statue of Erik standing high above the town, and Greenlandic Inuit run the sheep farms originally worked by Norse settlers.

We came ashore to find a Lutheran wedding in progress. Back in Erik the Red’s day, Catholicism ruled, and a church was built. Today, there is an exact replica of the original Catholic church that once stood on this sacred ground but don’t rush to get in, because only three to four people can fit inside what is thought to be the smallest consecrated Catholic church in the world.

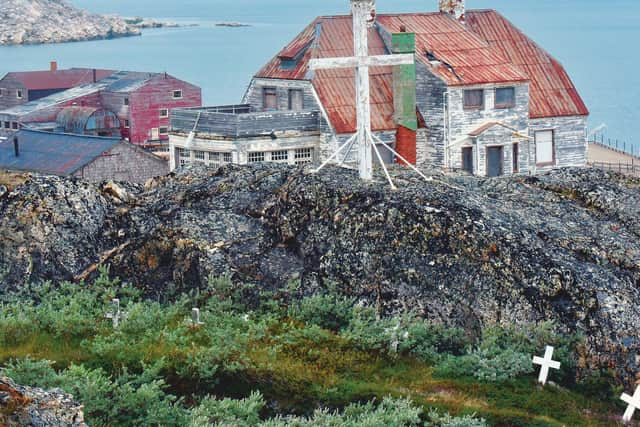

The west Greenland coastline is a rich mixture of fishing communities, islands and complex coastal waterways. We travelled by Zodiac through Arsuk Fjord to a vast waterfall as nearby, a single musk ox grazed the steep mountain side, and landed at Ivigtut, an exhausted cryolite mine, since 1984 a ghost town with abandoned buildings and crumbling homes. Ivigtut mine was an important site during the Second World War, when both the US and Canadian navies shared it, with 500 service men and three naval artillery posts.

Our next stop was Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, at the mouth of a huge fjord system, which was established as the very first Greenlandic town in 1728. A visit to the local museum will enlighten visitors about the story of the Norse in Greenland before sailing on to Evighedsfjord (Eternity Fjord), as the name suggests, a large fjord in southwest Greenland, which in fact terminates at Qingua Kujatdleq Glacier.

As the ship sailed towards Kangerlussuaq along the Sondre Stromfjord, a most spectacular ending to an incredible journey, nearby, the Greenland Ice Cap cloaked the length of the country. Vast and beautiful, it is easily spotted from a plane window, and was last thing I saw as I flew away.

FACTFILE

Adventure Canada, In the Wake of the Vikings. The next In the Wake of the Vikings voyage will be 13-24 July, 2021. Prices range from $3,495.00 to $14,795.00. All shipboard meals, including on deck barbecues, afternoon tea, 24-hour coffee, tea and snacks included. Not included: pre- and post-trip hotel accommodation; international/commercial and charter flight costs; alcohol and soft drinks, massage, gratuities (suggested at $15 USD per person per day).

Getting to Canada from the UK: British Airways and Air Canada fly from the UK to Ottawa (Canada)

www.adventurecanada.com

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director