Sky’s the limit: Man’s fascination with Everest

MAY 29, 1953. The world is still recovering from war. In the east, communism is on the rise and the Korean War is in its third year. In the west, rock ‘n’ roll is about to storm America and in Britain the age of empire is wheezing to a close. The young queen is about to be crowned at Westminster Abbey. The rationing of sugar, eggs and sausages continues. It’s the decade of the motor car, the television and the washing machine. And far away in the unknowable white wilderness of the Himalayas, a range stretching over 1,500 miles and five countries, two men are standing on top of the world.

“The news of the first ascent of Everest broke in Britain on the morning of the coronation,” explains Dr Huw Lewis-Jones, a historian of exploration and the editor of The Conquest of Everest, a new book of testimonies and photos, many never seen before, of the first climb. “The timing was perfect. People wrote that it marked the beginning of a great new Elizabethan age but in fact it was the last hurrah of empire. There was a lot of talk of ‘conquest’ and the ‘assault’ on Everest in the press. What’s so nice is the fact that the two men on the summit were a New Zealander and a Nepalese sherpa.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd so Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay watched the world curve from beneath their feet, unaware their quest was already being spun into myth. As fellow climber on the expedition, George Lowe, puts it in The Conquest of Everest, reaching the summit of the world’s highest mountain would prove to be a beginning, not an end. Later John Hunt, the 1953 British expedition’s leader, wrote, “Our ascent became a symbol of national status, a subject for sermons and The Goodies, a trade name for an Italian wine and for double glazing against the rigours of the British climate. The names of some members of the expedition have been given to schools, to streets, youth clubs, Scout troops, and even to three tigers in Edinburgh Zoo.”

It was an extraordinarily gruelling climb, years in the planning and months in the execution. It was the ninth time an expedition had attempted what was then deemed impossible. It began in early March when 13 men accompanied by 350 porters embarked on a 17-day hike into the Khumbu from Kathmandu and ended in late May at 11:30am one morning when Hillary and Norgay – a rangy beekeeper from Auckland and a Nepalese Indian sherpa born in Tibet – set foot on the summit of Mount Everest.

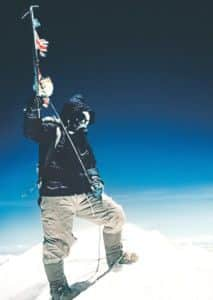

What did they get up to? They embraced one another and took photos looking down every ridge of the great mountain. Conditions were perfect. Just a slight breeze. Norgay left a bar of chocolate, a packet of biscuits and some lollies as an offering. Hillary collected a handful of stones from the highest point on Earth, shards of marine limestone that once, millions of years ago, would have nestled on the bottom of the ocean. He took a photo of Norgay holding up his ice axe, hung with the flags of Britain, Nepal, the United Nations and India. It would become one of the most famous images of the century. And then, after just 15 minutes, they began the hazardous descent down to the South Col where Lowe awaited with soup and hot lemonade. It was to Lowe, known as the forgotten man of Everest, that Hillary uttered the immortal words, “Well, we knocked the bastard off.”

Lowe, Hillary’s best friend and lifelong climbing partner, died in March at the age of 89. He was the last survivor of the 1953 expedition and The Conquest of Everest is his story; the crucial role he played in ensuring the success of Hillary and Norgay, and the extraordinary photos he took along the way of meals shared and disasters averted. Lowe used a kit bag stuffed with snow as a pillow, slept with his camera every night to keep it warm, snapped away during the day at the highest altitudes man had ever withstood, and thawed his frozen ink on a Primus stove so he could write letters home. Our obsession with the summit means this modest man who kept his ice axe in his umbrella stand and the lump of Everest rock that Hillary gave him on his desk has been overlooked.

“He is one of my heroes,” says Lewis-Jones who worked with Lowe on the book in the months leading up to his death. “George was very happy to play his part on that expedition. He never became famous like Ed and he never resented it. He cut steps for them to within about 350 metres of the summit and helped them place their very last tent. He was then left on the South Col, a very high camp, to receive them. It was George who took the photos and film of the expedition. He hasn’t really had the attention he deserved for any of it.”

“George Lowe was one of the very best in the way he selflessly worked away on the Lhotse Face,” agrees Sir Chris Bonington, the mountaineer who led the 1975 expedition that put the first two British men on the summit. “In the end they took two weeks to climb that face in very bad conditions – snowfall, high winds, the lot. That they were able to do so at all is thanks to George tirelessly cutting steps in the ice.”

Sixty years later, Everest continues to lure people to its flanks, slopes, crevasses, ice formations and rock faces, its very existence a challenge to humankind. Known to the Nepalese as Sagarmatha, and as Chomolungma to the Tibetans for centuries, the mountain was renamed by British colonialists after Sir George Everest, former surveyor general of India, in the 1850s. Everest himself opposed the name, telling the Royal Geographical Society in 1857 that it could neither be written in Hindi nor pronounced in Indian languages. Nevertheless, and in spite the unsavoury imperial associations, it stuck.

Sixty years on, the facts and figures remain mind-boggling. Standing a formidable 29,029ft high, the mountain is growing by an estimated 5mm a year as tectonic plates shift. The air is so thin up there – it’s not far off cruising altitude on your average commercial flight – that if you were plonked on top without acclimatising you would lose consciousness within two minutes. Some 223 people have died trying to get to the top. Still, by the end of 2011, there had been an astonishing 5,640 successful ascents by 3,450 climbers, some more famous than others. A 76-year-old man made it in 2008, and a 13-year-old in 2010. The first woman reached the top in 1975 while in 1980, in the most famous climb since Hillary and Norgay’s, Reinhold Messner did it on his own, without oxygen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1975 Doug Scott became the first British mountaineer to ascend Everest alongside Dougal Haston on Bonington’s expedition. “I tried twice in 1972 and finally managed it on this trip,” Scott tells me. “I became hooked on the place, hooked on climbing it. It was amazing to be in these legendary places: the Western Cwym, between Lhotse and the great south-west face of Everest, up on the summit ridge. And to find that I could cope up there. This was still a time when every team had the mountain to themselves. It was extraordinary.”

He arrived at the summit at 6pm, just in time for sunset. “We were just lost in it,” he says. “There were these huge, expansive views looking down the Nepalese valleys, the cloud forming around us, the purple plains of Tibet stretching out in the north. We could see Kangchenjunga, the world’s third highest summit, 75 miles away. We felt we were part of something so much bigger than ourselves.”

And then, of course, they had to descend. “We got down the Hillary Step and our torches failed,” he explains. “So we had to stay at the south summit, about 100 metres down from the main summit. It was a vertical drop. We had no choice but to spend the night there.” Scott and Haston dug a snow cave and prepared to sit on their rucksacks for nine hours, doing whatever they could to ward off frostbite and unconsciousness. The temperature was “at least” minus 40 degrees. They had run out of oxygen and had no sleeping bags. Somehow, they survived.

“It was quite a tough night,” he says in understatement. “Strange things happened. It was like a dream. I was chattering away to my feet as if they were two separate entities. I was asking the right one what we were going to do with the left one because it wasn’t warming up. And then the left one was replying to me – ‘why not use me to kick the right one?’” I laugh, but Scott doesn’t. “I remember getting the boot and sock off and seeing the foot had gone solid with frost,” he continues. “It took a full hour of pummelling to get the blood circulating. I had to put it under Dougal’s armpit for a time. Anyway it really widened the range of what we might do in the future. That night in the snow hole gave me a huge amount of confidence. I never climbed with oxygen again.”

Yet for many, the question remains: why climb Everest? Why risk your life to touch the roof of the world? When George Mallory was asked this question in March 1923, after two failed attempts, his reply became the three most famous words in mountaineering: “Because it’s there.” It was not to be for Mallory. He returned to Everest in 1924 for the third time and the last sighting of him and his climbing partner Sandy Irvine was by geologist Noel Odell who, from 2,000ft below, watched two “black spots” crawling up the summit ridge, higher up than any man had ever been, before “the whole fascinating vision vanished, enveloped in cloud once more”. Another two lives lost on Everest. Another unsuccessful bid for the highest point on Earth.

“Why do we travel to remote locations?” Mallory once asked. “We do it to be alone amongst friends and to find ourselves in a land without man.” Yet Everest today is a land swarming with men (and women) like ants over a hill. A rope – or “virtual handrail” as Scott puts it – runs from base camp all the way to the summit. Since 1986 when the Nepalese government changed the law to allow anyone who could afford it to go there, Everest has changed. The world’s highest mountain has become a tourist attraction. Now you can access wifi at base camp, hire sherpas to cook, clean and attach ropes for you if you can afford the £40,000-plus fee, and get a phone signal all the way up. At the top, you can tweet or upload a video on to You Tube. Go online and you can see exactly what it looks like at the top of the world. Like Glastonbury, you might say, only with thinner air.

Even more sinister are the stories of climbers stepping over dying people on their way to the summit where there are frequent bottlenecks at dangerously high altitudes. Or, more recently, the fights that broke out between sherpas and climbers on the side of the mountain. A relationship that was once epitomised by Hillary and Norgay ascending Everest side by side and grinning at one another for the cameras when they came back appears to have soured. In 2003 Norgay’s son said his father would have been shocked to see there are now people climbing Everest “who have no idea how to put on crampons”.

“It’s all about individuals now,” Scott says with a sigh. “Anyone can sign up for Everest, and that’s how you get so many disasters. No one is looking out for each other. It’s been said that the good Samaritan principle in climbing is dead. That’s why it’s important to remember the 1953 ascent. It’s a reference point. It shows us how it can be. Things aren’t so good on Everest now. The commercialisation of the mountain has got really out of hand. I don’t think it can get any worse. The commercial expeditions are basically taking clients up like dogs on a leash. You’re told which tent to occupy, when to open your zip to receive food and drink, when to go up and when to go down. The point of climbing is looking after your own life, making your own decisions, working together, but that’s not the case any more on Everest. It’s all about paying your money and getting dragged up there.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBonington is more sanguine about the changes. “Everest may be a nightmare now but the fact is it’s still the highest point on earth,” he says. “People will always want to go there and they still get a huge amount out of it.” Nevertheless, he’s relieved he finally made the summit in 1985, just a year before the law changed. “Thank goodness I got there when we were a single expedition who looked after each other and worked alongside the sherpas,” he notes. “We had the Western Cwym to ourselves, indeed pretty much the whole mountain. That was wonderful. When I finally got to the top it was a very emotional moment. At that time I was a mere youth of 50, and the oldest person to have done it. Also I couldn’t help thinking of those close friends of mine who had lost their lives on the mountain. It was a bittersweet moment.”

In 60 years life on Everest has changed dramatically. Yet how much has Everest herself changed? “I believe the mountain should be available to everyone,” says Lewis-Jones, who has never climbed Everest but has been to base camp many times. “That is the point of the mountains – they are free. The first ascent was about breaking the barrier of the possible, proving that it could be done. Now it’s no longer a question of whether it can be done, but whether you can do it. It would be wrong to say people can’t go, though if you’re looking for wilderness, you’d be more likely to find it in the Highlands than on Everest.”

Some things don’t change, however. “Everest will always represent the ultimate challenge for humankind,” Lewis-Jones notes. “And anyone who goes to the region is still changed by the experience. The mountain teaches us to face our fears, to face ourselves. You don’t need to go to the Himalayas to be tested, we can all find our own Everest, but it will always be this way. It’s the highest mountain on Earth. And we’ve only been ascending Everest for 60 years. It’s been millions of years since the mountain rose from the sea. When you look at it like that, we’re just a blip in her history.” n

Twitter: @ChitGrrl

The Conquest of Everest, Original Photographs from the Legendary First Ascent, by George Lowe and Huw Lewis-Jones, is published by Thames & Hudson, £24.95. Lewis-Jones will appear at the Borders Book Festival to discuss Everest and his collaboration with Lowe on June 15 (www.bordersbookfestival.org).