From Picasso to Jarman: new book lifts the lid on the endless appeal of pebbles

“On A Raised Beach” was published in 1934, while MacDiarmid was living on the island of Whalsay in Shetland. While exploring the archipelago he spent time with the geologist Thomas Robertson who taught him the technical terms for stones, many of which find their way into the poem. Once MacDiarmid has finished turning over these interesting new words in his mind, however, it’s the existential rather than scientific questions raised by the stones that capture his imagination: “I lift a stone; it is the meaning of life I clasp / Which is death, for that is the meaning of death; / How else does any man yet participate / In the life of a stone, / How else can any man yet become / Sufficiently at one with creation, sufficiently alone.”

Trips to the seaside have caused other writers to address a more prosaic but no less slippery question: what is the difference between a stone and a pebble? In his 1954 book The Pebbles on the Beach: A Spotter’s Guide, recently republished by Faber & Faber, Clarence Ellis observed that the usual dictionary definition of pebble –“a small stone rounded by the action of water” – was accurate but also problematic, not only because not every pebble has been rounded by water, but also because “there is some disagreement among the authorities upon the degree of smallness which a rounded stone must attain before it can be classed as a pebble.” And don’t even get him started on the vagaries of roundness: “it is impossible to fix upon one point in the long process of shaping and smoothing as a clear division between a rock fragment and a pebble.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

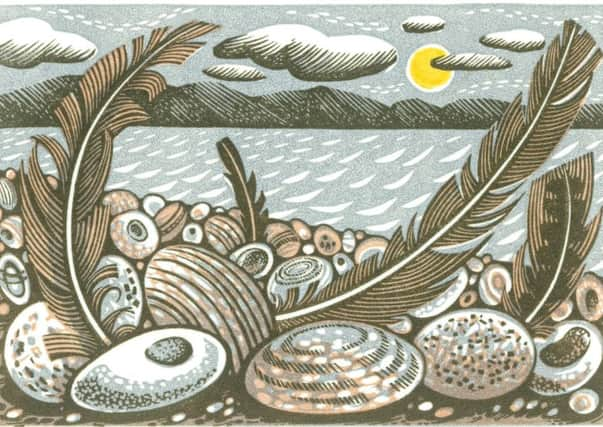

Hide AdWhatever we choose to call them, though, there’s no doubt that the small-ish, round-ish pieces of rock that line many of our beaches are of far more interest to human beings than they have any right to be, and in their newly published collaboration, The Book of Pebbles, writer Christopher Stocks and artist Angie Lewin set out to explain why. In the book’s foreword, Lewin, who is based in Edinburgh, explains that her attraction to pebbles has to do with an instinctive sense of aesthetics (“I’m no geologist, but I’m attracted to how they look and feel in the hand.”) She also notes how, viewed out of context, they can act as little portals into a whole scene: “a pebble defines an entire landscape for me,” she writes, “and through them, I try to depict the wild places I love.” As her interest in pebbles has grown, she says, so they have taken up more and more of the foreground in her work, and this is borne out by the linocuts, screenprints, wood engravings and watercolours that illustrate the book: pebbles and plants dominate; the rest of the landscape, if it appears at all, is usually partially obscured and somewhere in the far distance.

It falls to Stocks to attempt a more general explanation of our love affair with pebbles, and he approaches this task by mixing personal experience and cultural history. As someone who lives on Chesil Beach – perhaps the most famous shingle beach in the UK– he is uniquely well-placed to talk about the visceral appeal of pebbles: the sounds they make as they are ground together by the waves and their physical properties – their “weight and heft, their smooth shapes seeming almost designed to be held in the hand.” However, it’s really in his potted cultural history of the pebble where Stocks makes his mark.

Taking us on a whistlestop tour of the pebble in 20th century art, we visit Picasso at Dinard in Brittany in 1928, where he begins incorporating pebble forms into his drawings, and Henry Moore in Happisburgh in Norfolk in 1930, where he and Barbara Hepworth begin to fully appreciate the artistic potential of the pebble. There are also detours via Jim Ede’s pebble collection at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge and Derek Jarman’s pebble sculpture garden beside his hut at Dungeness.

The geologists get a look in too – notably John Hutton, the father of modern geology who had his eureka moment in Berwickshire – but for Stocks, much like the artists he references, pebbles are ultimately more interesting for what they mean than for what they are. In his conclusion, he reflects that the sound of pebbles being ground together is both the sound of them being made and the sound of them being destroyed. “Could it be,” he wonders, “that, perhaps without really knowing why, we take pebbles home with us to preserve them? By taking pebbles away from the beach, we arrest an otherwise ineluctable process of decay. It’s as if we are trying to stop time in its tracks.”

The Book of Pebbles, by Christopher Stocks and Angie Lewin is published by Random Spectacular, £14.99, see www.thebookofpebbles.co.uk