New book launch for fashion photography pioneers Condé Nast

From the very beginning in 1892, Condé Nast attracted the best creative talent as the publisher knew the key to success lay in the skills of its image makers. With the appointment of Edward Steichen in 1923, fashion photography was born and as the century progressed it became an art form in itself. Its most talented proponents ,Steichen, Beaton, Blumenfeld, Newton, Bailey, Day and Testino, all worked for Condé Nast and were celebrated in their own right.

So it was to the Condé Nast archive that photography and art historian Nathalie Herschdorfer went to study the development of fashion photography, opening up boxes of prints, many of which have been unseen for decades. The result is an international exhibition that opens in Edinburgh and accompanying book showcasing the work of 86 of the 20th century’s greatest fashion photographers, both entitled Coming Into Fashion: A Century of Photography at Condé Nast.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I looked at thousands of images but reduced it to 200. This project is about the history of fashion photography because it reflects the history of photography itself from the 1920s to today, from style to equipment, because that’s where the money was to create and explore. It also tells us about how women were represented and our perception of female beauty,” says the curator.

This hasn’t changed as much as we might think. Like today’s airbrushed, manipulated images, back in the 1920s the silhouettes were slimmed down, skin improved and noses tweaked. There’s nothing new about striving to create idealised images.

“It’s not a natural thing, it’s about representation and seduction,” says Herschdorfer. “These photographs did the work for the society of the time so you see women moving from domestic roles out into the world. There’s a subtext, especially in wartime and after, and it’s consciously done,” she says.

In contrast to the images’ appearance in magazines, there is a total absence of branding and logos as the photographers were rarely interested in fashion per se. Coming into Fashion wastes no time on captions and you may recognise the Kates and Cindys, but they’re not named. “It’s about the image and the photographer,” says Herschdorfer.

“Nowadays the photographers who do fashion images also have careers as artists. It just happens that some of their pictures are fashion. We don’t care if the shoes are by Gucci or the clothes by Chanel. Fashion photography is meant to seduce, to sell fashion, but these photographers all had something different. They said something about the period, about women, about society, about the human spirit.” n

Norman Parkinson, Glamour, 1949

“Parkinson was discovered with British Vogue and brought to the New York headquarters. The image is showing a woman as active, racing to work or to meet someone. It’s about a new role for women being out there in society because the economy needed them. It’s also about New York and its place in the world and in fashion. When you look back through the magazines in the 1920s, fashion is always about Paris and haute couture, but post-war it’s New York, a modern city. In Europe there was still no money for fashion, but in America there was.”

Clifford Coffin, Vogue, 1949

“This is a timeless image. You could see this today on a cover. Maybe a fashion specialist would say those bathing suits are typical of the 1940s but that’s not what it’s about. What are they doing. What are they looking at – ahead into the future? And the composition is a delight for the eyes, the balance and construction is perfect – the sunshine, sand, the little dots of red and blue hats, the lines of the bodies, dunes and sky, leading you beyond. This is a photo that gives you an impulse and something for the viewer to think about. It’s very open. When you look at such an image you realise that the balance and construction is perfect.”

David Bailey, Vogue, 1962

“After the 1940s when colour was new there was a return to black and white in the 1960s. Having something look more like a snapshot and grainier was also new. It’s not a studio shot because Bailey wanted to do something in the street – he is on the other side – and it’s New York. He was brought from British Vogue and they wanted him to bring some of the Swinging London style and spirit to the magazines. He came with the 18-year-old Jean Shrimpton, the first famous professional model and they became the It couple of the day.”

Sølve Sundsbø, Love, 2011

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This is a very contemporary image and is all about retouching. Nothing is real or natural and it doesn’t try to hide that. The skintone, the body, hair and grapes are all retouched. It could be a drawing, a sculpture, although the elegant pose could be 1940s. It is really a photograph or not when there’s so much retouching? Today’s fashion photographers also work with video and digital tools and Sundsbø plays with all of these. He did this image for Love magazine in 2011 in London. Condé Nast launched Love to be more “edgy and experimental” and the biannual can be more adventurous with this than Vogue. They couldn’t do this in Glamour or Vogue New York.”

Constantin Joffé, Vogue, 1945

“This is an image of an active woman in the city. She’s on her way somewhere, not stuck in the home. The first two decades of fashion photography showed women in the studio but here they have started to get out on to the street. She doesn’t pose or look at the camera. She’s very elegant and beautifully dressed, but she’s busy. In the 1940s women were being encouraged to play a role economically and magazines were part of selling this message. There’s also a strong use of colour which was popular at the time.”

Edward Steichen, Vogue, 1923

“Steichen was one of the inventors of fashion photography. He wanted the images to look like real life not catalogues and as professional models didn’t exist he used Broadway actresses who knew how to pose instead of society ladies. Later Hollywood stars like Katharine Hepburn were used so it became about celebrity as well as fashion. He had little interest in fashion and was criticised by editors for not focusing on it.”

John Rawlings, Vogue, 1943

“The message here is that everyone can do their own make-up with the beauty products being sold in the magazine and you don’t need a lot of money to do this. Vogue wasn’t for high society but for secretaries who like to dream. Things haven’t changed; we can’t afford Dolce and Gabbana but we can dream, we can’t afford the clothes but the beauty products we can. Magazines in the 1940s were full of clothes patterns to make yourself without spending a lot – there was a war on. This woman is elegant, and you can be too.”

Deborah Turbeville, Vogue, 1975

“When she did this she was absolutely unknown as a photographer. This was her first shoot for Vogue and they gave her several pages for a story in a public bath in New York. Everyone thought it was shocking, these women by themselves, it’s erotic, photographed by a woman and showed a new spirit in Vogue. There was a lot of discussion about whether they should publish it and they lost many subscriptions over this issue and were more cautious afterwards.”

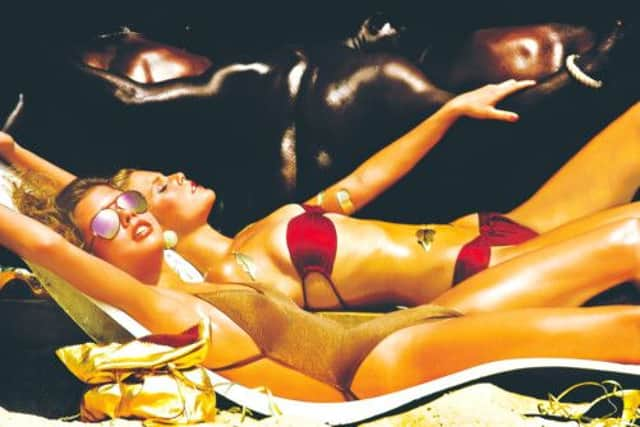

Albert Watson, Vogue, 1977

“This is very glam and very much of that era. I don’t know if you would do that today, showing the black males in the background. There would more be questions about this image. In the 1970s it wasn’t such an issue. Magazines have to attract people, have to sell, to seduce. Fashion photography is all about glamour. You have to shock and you don’t want people to be bored, but it’s a balance and very sensitive and some editors won’t do it.”

• Scotland on Sunday is official media partner with The City Art Centre, Edinburgh, for Coming Into Fashion: A Century of Photography at Condé Nast, as part of Edinburgh Art Festival, 15 June until September 8, City Art Centre ,Edinburgh (www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk, www.edinburghartfestival.com); Coming into Fashion: A Century of Photography at Condé Nast, by Nathalie Herschdorfer, £42, Thames & Hudson