Our Yorkshire Farm's Amanda Owen's recipes for happiness -

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

Think you’re busy? Compare yourself to Yorkshire Shepherdess, farmer and writer Amanda Owen, star of Channel 5’s Our Yorkshire Farm, who lives at Ravenseat Farm in Swaledale, Yorkshire with her husband Clive and nine, count ‘em, children, 175 sheep, 50 hens and a few cockerels, around 20 cows and a bull, five sheepdogs and two horses - Tony the pony and a new Clydesdale, Hazel.

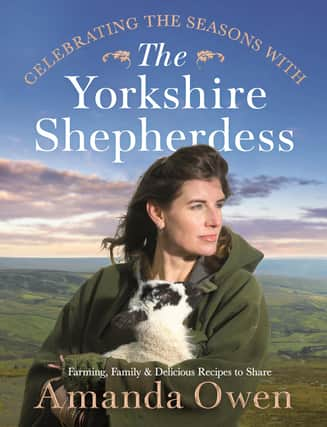

That’s busy. It’s a lot of rearing and feeding, both human and animal, which is why she’s supremely qualified to write (in the wee small hours when everyone’s asleep) Celebrating the Seasons with The Yorkshire Shepherdess - her fifth book - comprising her go-to family recipes, along with stories and her own beautiful photographs of farm life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnflappable and practical in approach, she’s vibrant and enthusiastic in personality and as well as winning fans with her books about life on a Dales farm, the TV show draws in three million viewers an episode.

Living at Whitsundale at what Owen calls “one of the highest and most remote farms in England” means she has to be organised as winter snow often sees them cut off. She shops in bulk - she’s a regular at the army’s Catterick camp stores and agricultural suppliers where she buys potatoes by the sack - for her sizeable family of children ranging in age from five to 19 Raven, Reuben, Sidney, Annas, Violet, Miles, Nancy, Edith, Clemmie and Nancy (not necessarily in the right order) and quantity, cost, ease and flexibility are key when it comes to meals.

Tracking a year of life at the farm, the recipes follow the seasons and Owen is big on using local produce, if possible, produced at or foraged near the farm. “Eating what is in season is easier on the pocket, and naturally more nutritious and flavoursome” she writes, and with many hungry mouths to feed, she specialises in filling, hearty meals: “It’s yer belly that keeps yer back up’.

Spring and summer mean Elderberry and summer berry pavlova with foraged fruits while autumn is Wild Mushroom with Wood Sorrel and Hazelnut Pesto Soup with homemade bread, and winter sees her cooking “potatoes all ways, heaps of root vegetables, roasts and pies like Creamy Ham and Cabbage, and Hedgerow Nutty Crumble and custard.

Owen comes on the phone sounding calm and collected, but she’s interrupted and has a hurried, whispered conversation before she comes back on the line.

“Did you hear me there?” she says.

Was that Clive, looking for a hand with something? I ask, thinking she’s probably up to her elbow in either a sheep or dough, as she multi-tasks while talking to me.

“No. It was the Mayor of London,” she says.

Right. I’ve already clocked from the book and TV show that Owen has a sense of humour.

“No, it really was,” she says, another character trait being calling a spade a spade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’m in London,” she explains. “Yesterday I drove sheep over Southwark Bridge. I’m in a state bedroom!,” she says, not quite believing it herself.

Sure enough, she is in London, having been invited down to lead the annual Sheep Drive and Livery Fair, organised by the Worshipful Company of Woolmen to celebrate the Freemen of the City’s ancient right to move sheep over the River Thames. The charity provides support for sheep farming, shearing, wool production, textiles and design so it’s fitting that Owen has been chosen to lead it this year.

“London was built on trade and sheep, and bringing them across the bridge is reminding people of its humble beginnings and where it all began. It’s absolutely the most random thing I’ve ever done,” she says. “I couldn't believe it. It was one of those cases of maybe I should have read all of the email, because I get down here and get invited into a state room at Mansion House and think, Oh my God.”

Removed from Whitsundale, as well as driving sheep over bridges she’s still helping Clive oversee life back on the farm, as she does publicity interviews for the book, and is finding the busy metropolitan milieu challenging.

“Ugh god. I'm walking around around in circles. Seriously, I feel like I'm corralled today.”

Owen isn’t used to days out. Rare as hen’s teeth, they usually take the form of a visit to a ram or bull sale or agricultural show where, as Owen puts it, “you're praying to God the weather is going to be crap because otherwise you think you should be at home clipping or hay turning. Farmers are always farming. They just can’t switch off,” she says.

“The farm is always there. It’s a constant in my head. I’m thinking OK, I’ve got someone coming to build the barn, I’ve got a load of hay arriving... My brain is like a computer with lots of windows open all the time,” she says happily, not sounding remotely overwhelmed by it all.

“That’s just my life. The next job is back up on the train and back to the farm tonight.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRaised in Huddersfield, with no family links to farming, Owen always wanted to become a shepherd and by the age of 21 had met Clive when she went to his farm to borrow a tup (ram) and moved in with him at the 17th century farmhouse at Ravenseat.

Children followed, and followed some more. Clemmie, number eight, was born beside the farmhouse fire while Clive and the other children slept upstairs. Does Owen think she’ll have any more?

“I don’t know. I’m quite old now, 48. But as you can see, I’m not a planner, so I think we’re going to have to say, I don’t know. Never say never.”

A big family wasn’t planned, but it wasn’t not planned either.

“The only thing I wanted to be was a shepherd and I didn’t know how I was even going to do that. There was no sit down conversation, hey let's have a massive family, it just was the right place to be able to do that, so why not?”

Never mind days out, the pair have only ever been away on holiday once and that was prompted by extreme circumstances.

“It was 2001, the year of Foot and Mouth when they killed our stock and it was just so horrible we needed to get somewhere very far away where the weather would be okay, so we went to India. We enjoyed it! But yeah, that was the reason.”

So is the key to cooking for a large family, on a budget, speed and what does she look for in a recipe?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’s not necessarily about being fast,” says Owen, “Meals need to be something I can start making, get completely distracted and forget about, go back and put in the oven, find something else to do and it won’t be completely knackered if you go back two hours later, that’s pretty critical.

“Also, anything you can make your own. Politely it’s called fusion, but what I actually do is if you haven’t got the right ingredients just use something from the fridge. I’m also very mindful of the cost, nothing too expensive, and nothing crazily mad - it has to be stuff that’s in the store room and available. Also I've got a big family to feed and they need lots of food, so little dainty portions are no good. Usually it's just family, but with their friends and people who come to the farm, if you’re there at mealtime, you get dinner, and whether you get a bigger portion or a littler portion depends on how busy I am.”

Although the Owens keep sheep, mostly they’re sold on for breeding, but lamb will sometimes feature at mealtimes, as in book recipes Wild Garlic Lamb with Hasselback New Potatoes or the family favourite, Moroccan Lamb Tagine with Jewelled Couscous.

“My favourite is definitely the Moroccan Stew, because it’s lovely and forgiving. It’s easy, just ten minutes preparation and it’s really a stew dressed up with lots of spices. You can chuck apricots in it, serve it with couscous or flatbread. Just leave it alone and it comes out unctuous, saucy and utterly delicious. Plus I don’t have to yell for the kids because they can smell it a mile off.”

A day out in London is a change from the usual routine of up at six, pack kids off to school, work around the farm with Clive, kids home, feeding and bedtime routines, then writing.

“I’m always chasing my tail, always got tonnes to do, but I don’t need a lot of sleep,” she says. “I write into the early hours because that’s the only quiet and peaceful time that I actually get when I can have space to think.”

Using local produce, sustainably produced, in season, Owen’s methods all make sense, particularly with the supply chain problems the UK is now experiencing.

“I hope so,” she says. “But it's not a manual to live by. It's certainly not a blueprint of ‘this is how you do things’ because that would be really, really annoying. It is more of a ‘hey, this is how we do things, use it as a guide, take from it what you want’. The whole idea is take a bit of this and a bit of that. I’m a more free and easy, go with the flow kind of person so here are the recipes but I tell you what, if you don't want to follow ‘em, don’t.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSwitching ingredients, adapting, anything that will make life simpler, just do that... would she say that’s her mantra for life?

“Yes! Of course. What I say is where can I lower the standards? What actually really matters and what doesn't? What matters is, are the kids happy? Yes. Does it matter if things match and are perfect? No. Is everyone sort of in a good frame of mind with a good mindset? Is life going on? Yes. Well, that will do. Anything else is a bonus.

“I'm not a domestic goddess. I'm not anywhere near perfection. Of course I'd love things to be tidier, I'd love there not to be dust. I'd love there not to be felt tip on the walls. But is that really, really, really gonna make me happier? No.”

As viewers of Our Yorkshire Farm will know, the Owen children are always out riding, swimming in rivers and revelling in an environment surrounded by animals and farm machinery. Does Owen worry about the children’s safety?

“You wouldn’t be a normal parent if you weren't worrying about what might happen but I give myself a little kick and say life is there to be lived. And the most dangerous thing you can do is actually not give children any experience of danger. That doesn't make things safer. They need to learn how to manage and control it. Who would ever get on a horse, get in a car, go out of the door if you said ‘I don’t want you to get injured’. It's about managing it and I want them to push themselves and enjoy themselves. That's where they get their best lessons.”

As it turns out the worst accident that befell one of the children could have happened anywhere and was down to their mother.

“It was the most mundane thing ever,” she says. “I chopped Rueben’s finger off in a door. It was hanging off by a string. He was in a backpack on my back, and I got hold of the door and pulled it shut. There was like a moment’s silence then a scream and of course he’d put his little hand in the hinge. It was horrible. I was mortified and I cried all the way to the hospital. But they sewed it back on and it was fine. He can give you a finger, no problem. So after all the driving about and balancing on horses and going swimming, it was shutting a finger in the door.”

Spending so much time around animals, Owen feels she has learned a lot from watching them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I think when I gave birth to Clemmie on my own, I learned to read the signs and not have fear. They don't know about animals, how much they know about when they're giving birth, about what is going to happen, but it's a natural process. They have no sense of expectation, of how they intend it to be.

“You can read the physical and mental signs, so you know when a sheep is gonna lamb by how she is, her mannerisms. You learn about the practicalities and everything is adaptable. When I had mastitis, I knew because I've seen enough sheep with it. When I had Raven, my firstborn, and the doctors said there were signs of meconium, I knew that meant foetal stress, because it's exactly the same when you’re calving a cow or lambing a sheep. If it's bright yella, it's because that newborn was stressed through the process of labor and birth.

“So we're not that far removed from animals. The night I had Clemmie, I couldn't sleep, I was making myself a cup of tea and walking around in circles, that's exactly what a sheep would do. Not make themselves a cup of tea, obviously, but walk round in circles, and they can’t rest. It’s the same.”

With this, her final interview for the day over, Owen just has time for another chat with the Mayor of London then it’s back on the train to Yorkshire. She already knows what she’ll be making for dinner tonight when she arrives at Ravenseat with its farmhouse lights glowing out across the moor and all of the kids hungry around the big kitchen table.

“Tonight we’re going to have the old classic, so boring, but great - sometimes boring done well is great - we’re having baked potatoes. Rub ‘em in oil, sprinkle ‘em with salt, straight onto the grill shelf in the Aga and just leave them alone. They come out crispy on the outside and beautiful and really soft on the inside. With a great big wodge of butter, maybe some tuna, maybe some beans; it’s just soul food. Simple, simple, simple, cheap, cheap, cheap. And you can’t do that in a microwave.”

True, but if you don’t have an Aga, or maybe even an oven, a microwave will do. Just follow Owen’s advice and lower your standards. Go with the flow. It’ll be right.

Celebrating the Seasons with The Yorkshire Shepherdess by Amanda Owen is published 28 October by Pan Macmillan, £20.

online, please can you add a click through where readers can buy the book here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Celebrating-Seasons-Yorkshire-Shepherdess-Delicious/dp/1529056853/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChannel 5 called Our Yorkshire Farm, which has become one of the channel's most popular programmes with over 3 million viewers watching each episode