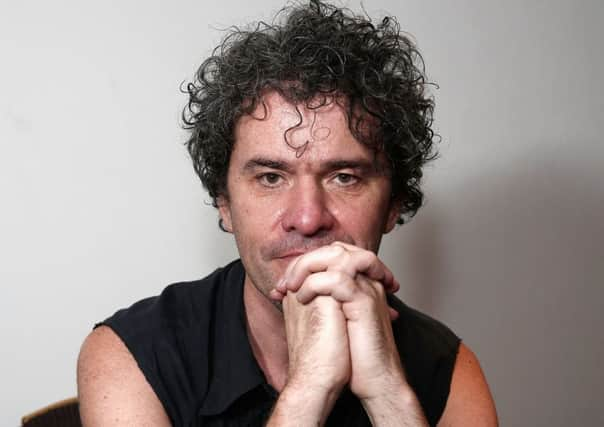

Film Interview: Mark Cousins on The Eyes of Orson Welles

The blown-up eye provides a neat symbol for both this show and Cousins’ new film, The Eyes of Orson Welles, which uses a treasure trove of Welles’ paintings, drawings and doodles – many of which are displayed here – as a prism through which to examine this most visual of storytellers.

“This one’s quite Churchillian,” says Cousins, pointing to a playful, pumpkin-shaped self-portrait near the start of the exhibit. Further along there’s a caricature of a whale, a reference to his role in Moby Dick — only he’s turned it into another self-portrait by giving it a Wellesian eye. “It’s an interesting way of portraying himself. He was a fat man, but he loved making himself even fatter in drawings.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe sheer size of the man can be gauged from the boot sitting in the exhibition’s first display case. Cousins bought a pair of Welles’ boots in an online auction, fully intending to wear them, “but the ankles are about three times the size of mine.”

Yes, the creator of Citizen Kane wore shoes that are literally too big to fill. Luckily, Cousins wasn’t interested in treading old ground.

“When I make something I tend to list the received opinions and strike them out. So the received opinion about Welles is that he started at the top and worked his way down, or that he was a self-saboteur. I just thought I was going to ignore those and, based on this material, come up with a structure that would feel fresh.”

The film and the exhibition grew out of a meeting with Beatrice Welles, Orson’s youngest daughter and owner of the archive. She wanted to exhibit the pictures and Cousins told her they could do it in his home city of Edinburgh. “Orson Welles came to the festival [in 1953] and Summerhall is kind of a funky place that fits with Welles’ aesthetic, especially later on, so that’s why we’ve got it first. She’d also seen my Story of Film thing and asked if she thought there was a documentary in these drawings and paintings. As soon as I looked at them I thought, ‘Yes’. Welles didn’t keep a diary of any sort, but these are sort of like a diary. You can sometimes tell where he was and what he was thinking.”

We look at a series of sketches he did as a teenager of buildings in Geneva and Genoa. His cinematic obsession with architecture is already evident. “He was called a genius from the age of eight so every scribble was considered valuable.”

Our eyes move along the display case.

“Now these are rather good.” He points to a series of Christmas cards featuring Raoul Dufy-esque watercolours of Paris. “He loved art and when you’re looking at his drawings and paintings, you’re dealing with someone who is very articulate about art history.” Across the exhibition Cousins points out pictures influenced by Tintoretto, Picasso and Rothko. “Welles was seeing all the shows, seeing loads of art.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHe absorbed everything and the film illustrates how engaged he was with the world around him, especially politics. He didn’t wait around to call out fascism, for instance: it was there in his theatre and radio work of the 1930s, it was there in his film work, and it’s here in these sketches.

“Look at these,” says Cousins, pointing to a series of rough designs for a film version of Julius Caesar that never came off. “They’re pictures of the Colosseum, but that middle one is from the Mussolini district in Rome. So you have these visual things overlapping, connecting the fascism of Caesar’s period with the fascism of the 1930s.” The pictures aren’t exactly storyboards, he says. “They’re better than storyboards; they’re faster. He’s drawing visual moments. He’s drawing where he wants your eye to go. He’s working out the image system of the film.”

Advertisement

Hide AdLike a lot of the work on display, these sketches signify a creative mind working faster than his chosen medium. It’s why Cousins can’t get on board with the notion of Welles’ great decline. “There was no decline. There was a dispersal of energy I think … The technology was a frustration to him. It took so long to do everything in cinema.”

Cousins himself likes to work fast. The Eyes of Orson Welles took him about four weeks to write and edit (the research and shooting took a little longer). He says he gets bored and wants to get onto the next thing (this is his third film this year). But he also thinks there’s value in responding to things this quickly, this instinctively.

“When you’re working at that speed it’s more like falling in love. Your emotions are working more than your thought process. I was feeling this stuff and trying to get that feeling into the film.”

His encounter with Welles’ lighting-fast sketches also enabled him to shake loose his own thoughts on films he’s been living with for decades. His Rosebud moment in The Eyes of Orson Welles came towards the end of that four-week flurry of writing and editing. Rewatching The Lady of Shanghai, he noticed the elaborate way Welles had filmed a cigarette being lit for Rita Hayworth’s character. “There was no story reason for that. It was just the pleasure of a line. It’s taking a line for a walk and I was like, ‘F**k, that’s it!’”

As we exit the exhibition, Henry Mancini’s theme for Touch of Evil starts playing over the PA system. Suddenly, something about that film’s famous single-shot opening scene becomes clear: it’s an example of Welles painting with the camera. “Isn’t it?” says Cousins. “If we’re saying that the technology of cinema for Welles was too cumbersome, and what he wanted was the liberty of a brushstroke, that’s it in a nutshell. And it was the force of Welles that he could make them do that. If we look at many of these drawings, we see how infrequently the pen or brush lifts off the page. It’s a single brushstroke. It’s the instinct of an artist without a doubt.” ■

The Eyes of Orson Welles is in cinemas now. The exhibition, Drawings and Paintings of Orson Welles, is at Summerhall, Edinburgh until 23 September.