Book review: Alone, by Christophe Chabouté

To describe these books as “translations” implies there’s a lot of text to deal with, but in fact The Park Bench barely contains any words at all. There’s no dialogue, no narration – just the occasional T-shirt slogan or book title to be rendered into English, as Chabouté’s colourful characters come and go through the seasons, their individual micro-dramas playing out on and around the titular bench. The details of their relationships and inner lives are as minutely observed as in any Jane Austen novel, but relayed to us via their expressions and body language.

If anything, Alone is an even more nuanced piece of visual storytelling, although it relies more heavily on text (translated by Ivanka Hahnenberger). Again, Chabouté uses a static location to tell his story – in this case a lighthouse perched on a rock in the middle of the ocean, where the deformed son of the former lighthouse keeper now lives in complete isolation. Because of his deformity, we learn, his parents never took him off the rock while they were alive. His mother died first, then his father, who left instructions for a local fisherman to keep dropping supplies at the lighthouse every week, but never, under any circumstances, to interact with his son.

Advertisement

Hide AdThis has been going on for 15 years when the fisherman hires a new deckhand, who learns the story of the hermit and decides to try and help him. One week he secretly leaves a note taped to one of the boxes of supplies which simply says “Is there anything special you would like?” and from that moment on, the hermit’s life is changed forever.

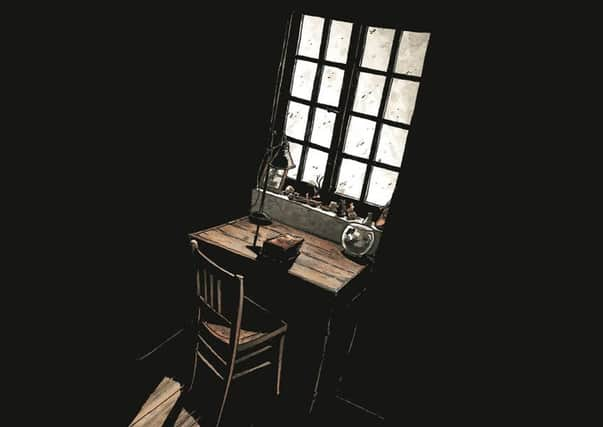

Chabouté’s great skill in Alone is using tiny visual details to manipulate his readers’ emotions. When we are first allowed a glimpse of the interior of the lighthouse, for example, we see all the treasures the hermit keeps on the windowsill behind his desk: a picture of his parents, as you might expect, but also a child’s toy car and a small plastic spade – mementos, perhaps, of happier times. Similarly, minute changes in the facial expressions of the hermit’s goldfish – his only companion – are made to speak volumes, not least when the hermit sits down to eat a fish he’s just caught for his dinner.

As with all prisoners, the hermit’s great allies are routine and imagination. He fishes every day, picks up his supplies from the quayside every week. He only appears to own one book, a dictionary, but by opening it on a random page each evening, then closing his eyes and putting his finger on an entry, he is transported to some weird and wonderful places –not least because his understanding of the real world is far from perfect. The entry for “confetti,” for example – “round pieces of coloured paper that people throw at parties” – conjures up images for the hermit of smiling people lobbing frisbee-sized discs at each another.

Another word the hermit lights upon in one of his dictionary sessions is “labyrinth” and Chabouté is ingenious in the way he portrays the interior of the lighthouse as an inescapable maze. Of course, it isn’t really a maze in any physical sense, but by briefly presenting it as such, Chabouté is perhaps alluding to the way in which we all, to some extent, become trapped in mazes of our own making – mazes we can sometimes only escape from with a little help from the outside.

Alone, by Christophe Chabouté, Faber & Faber, 384pp, £15.99